In the second blog we cited a brief history of the Rohingya people and observed the development of their plight from the end of World War Two until the 1980’s. In this segment we will consider the devastating impact of the Citizenship Law, in what state they live in refugee camps and their present day circumstances.

Whilst the oppression and massacres carried out by the Burmese government and army devastated the Rohingya, nothing has dismantled their community like the 1982 Citizenship Law causing their desperate plight today. The most critical issue remains the lack of legal status, or statelessness, of the Rohingya in Burma and subsequently Bangladesh and the implications this carries.

“To Burma the Rohingya’s are not people.”Amnesty International

In the wake of the mass exodus fleeing Operation Naga Min, those who survived the atrocious conditions of Bangladeshi refugee camps were forced to return to Burma. The government enacted the Citizenship Law targeting the returning Rohingya designed to exclude them by severing their legal ties to their homeland. Citizenship was only for those who satisfy one or more of the following three criteria:

1) The person belongs to one of the national races, such as Burman or Rakhine – but incredulously the Rohingya were not considered of the national races.

2) The person is able to provide proof of ancestors who settled in the country before 1823, the beginning of British occupation of Arakan State.

3) The person is able to provide ‘conclusive evidence’ that either he or his parents entered and resided in Burma prior to independence in 1948. Beyond these qualifications, Section 44 of the Act stipulates that the person must be eighteen years old, be able to speak well one of the national languages to which the Rohingya language, a dialect related to Chittagonian, is not one.

Successive Burmese governments have used the law to deny citizenship to an estimated 1.3 million Rohingya by excluding them from the official list of 135 national races eligible for full citizenship. According to Thomas Feeny of the Refugees Studies Centre, Oxford University, “These stipulations effectively deny to the Rohingya the possibility of acquiring a nationality. Although Rohingya history may be traced back to the eighth century, Burmese law does not recognise the religious minority as a national race, and as many Rohingya families settled in Arakan during the British colonial period they are immediately excluded from citizenship. Those Rohingya who cannot satisfy the demand for ‘proof’ or ‘conclusive evidence’ of their ancestors are thus disqualified from the running altogether, despite the fact that a large proportion of Rohingya are illiterate and lack written evidence.”[1]

Human Rights Watch states “The stipulations of the Burma Citizenship Law governing the right to one of the three types of Burmese citizenship effectively deny to the Rohingya the possibility of acquiring a nationality”[2] while Amnesty International state “To Burma the Rohingya’s are not people.”[3]

“When they confiscated our land we cried, but we had no way to say anything.”

The Citizenship Law effectively made hundreds of thousands of Rohingya a stateless people, devoid of any citizenship, recognition or protection in every country of the world. As a result, they reside without legal documentation or identity, are restricted in travel, access to work, welfare, education, freedom to press rights and practice their religion. This lasts until today where in December 2014 the UN General Assembly adopted a resolution calling on the Burmese government to amend the 1982 Citizenship Law so that it no longer discriminates against the Rohingya.[4] It is for this reason the United Nations labelled the Rohingya Muslims of Burma as “the worlds most persecuted minority.[5]

Unrecognised by either Burma or Bangladesh as legal residents, hundreds of thousands of the Rohingya are forced to live in refugee camps. Human Rights Watch described the reason for fleeing Burma into Balngladeshi camps stating,

“Initially, villagers may say that they have come to Bangladesh because they were unable to make a living in Burma, but under more thorough questioning it may emerge that the reason they were destitute in Burma was related directly to the use of forced labour, arbitrary taxation and the confiscation of goods and land from Rohingya.”[6]

Conditions in the camps have been dire. There is acute overcrowding and for many, the boundaries of the camp are the boundaries of its inhabitants’ world. Open sewers run in the camps inviting disease. Camps have one latrine for every 20 refugees and while adults may frequent these, children often use the sewers. Children under the age of 18 make up more than 50% of the officially recognised Rohingya population. The vast majority of children below the age of 5 run around naked. The few who do wear clothes usually have one outfit, which they do not wash regularly due to a combination of a lack of water and simple unawareness of hygiene matters.

“I think one of the most important things is to put an end to discrimination against people because of what they look like or what their faith is. And the Rohingya have been discriminated against. And that’s part of the reason they’re fleeing.”Barak Obama

Water rationing is a common feature of the camps. At one point, 56% of women in the camp were malnourished. Over 50% of newborn children exhibit signs of malnourishment between 18-23 months old. Family planning is as low as 5% with high levels of sexually transmitted diseases present. Early marriage is a norm. The Burmese government presently forbids any child who does not possess proof of citizenship to receive any tuition beyond the most basic primary education. Rohingya thus have no access to secondary schooling, and are heavily disadvantaged in seeking employment as a result. This results in very few children being engaged in any kind of activity. Most roam around the camps in small packs looking for something to do. Almost a quarter of children drop out of school to work at stalls or lack of motivation due to lack of school supplies or vocations. Harassment and violence from locals outside the camp is regular, including human trafficking and drug or gun smuggling.[7]

One member of the Rohingya community was recorded describing their ordeal stating, “In Burma we are forced to build roads. We are forced to build jetties and piers and military camps. We are forced to work sentry duty at night. If we doze off from exhaustion we are beaten. When we wake up we are beaten. And when we are beaten we are made to give away a chicken to pay for our punishment. My father was a farmer and had some land but it was confiscated by the military to build a military camp. I can remember working in the field with my father. When they confiscated our land we cried, but we had no way to say anything.”[8]

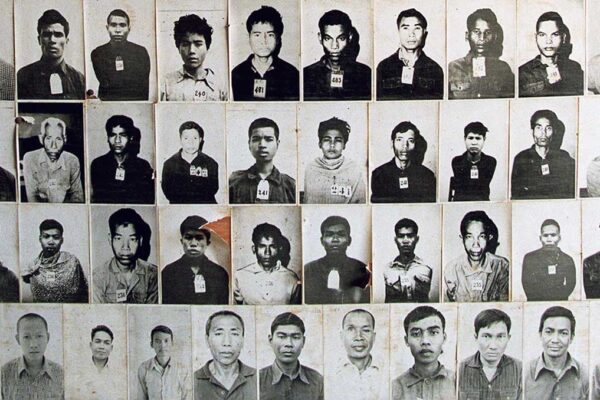

Such systematic human rights abuses conspired to drive another 250,000 ethnic Rohingya into Bangladesh in 1992. The government of Bangladesh refused to recognise any “new-arrivals” of Rohingya in Bangladesh as refugees, and denies them access to refugee camps or the protection and assistance of UNHCR contending that they are illegal migrant labourers. Furthermore, because of the length of time these Rohingya have spent as refugees in Bangladesh, there is a growing tendency to view them as somehow distanced from the conflict that inspired their escape, and thus not particularly deserving of ‘protection’. This is especially true in the case of the children who have been born in the camps and have grown up without actually experiencing the persecution that still persists in many forms in their homeland. Yet these are just as much victims of conflict as those who bear the physical or mental scars, for their immediate environment, their childhood and in fact every aspect of their lives continue to be constrained by the conflict in Burma and their statelessness. [9]

In the last few years, awareness for the Rohnigya plight has been at the forefront the worlds news. Religious violence has resurfaced as genocide where Buddhists – including monks, considered as practioners of a peaceful way of life, have been captured committing the most brutal of crimes in an attempt to completely remove the Rohingya from Myanmar.[10] Ransacking of Muslim businesses, immolation of Muslims in the streets, the burning of entire villages[11] and mob beatings[12]are regular features of the oppression. Time magazine stated, “Burmese monks were seen goading on Buddhist mobs, while some suspect the authorities of having stoked the violence.”[13] The antagonism is spearheaded by the 969 group, led by a monk, Ashin Wirathu who, jailed in 2003 for inciting religious hatred, was released in 2012, referring to himself as “the Burmese Bin Laden” or as Time magazine called him, “The Face of Buddhist Terror.”[14]

In recent months, fleeing this terror and annihilation, thousands of Rohingya have taken to the sea in the hope that neighbouring countries would accept them as asylum seekers or at least refugees. In the past three years, more than 120,000 Rohingyas have boarded ships to flee abroad, according to the UN refugee agency. As many as 8,000 are believed by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) to be stranded at sea, often with dwindling food and fresh water supplies[15] and some boats even being attacked by the Navy.[16]

Countries have been very unwelcoming, refusing them entry into their waters for safety, nor allowing passing fishermen to help and not granting asylum or citizenship to the stranded. Thailand has turned boats away and refused resettlement. Malaysia has repelled them too. Bangladesh, already host to 200,000 refugees often refuses entry while Indonesia has also expelled them.[17] When asked how Australia would react to the stranded approaching, Prime Minister Tony Abbott shockingly responded, “Nope, nope, nope. Australia will do absolutely nothing that gives any encouragement to anyone to think that they can get on a boat, that they can work with people smugglers to start a new life.”[18] The plight of the Rohingya has become such a prevalent subject in the media it forced even US President Barack Obama to comment saying, “”I think one of the most important things is to put an end to discrimination against people because of what they look like or what their faith is. And the Rohingya have been discriminated against. And that’s part of the reason they’re fleeing.”[19]

Ultimately the world is facing an active and ongoing genocide – something even Nobel Peace Laureates united in describing it as in June of this year.[20] The reality is this issue cannot be solved by Australia or the surrounding countries. This ghastly situation is the result of four generations of national persecution with impunity. It requires the people and government of Myanmar to change both their attitudes and law, to remove the Rohingya as a stateless community. And it is the topic of ‘what is statelessness’ that we shall, God-willing, explore in the next blog.

Read parts one and two of this blog below:

Part 1: The Rohingya Muslims: Understanding the plight of statelessness

Part 2: The history of the Rohingya Muslims and the development of their plight

- [1] http://www.rsc.ox.ac.uk/files/publications/other/dp-children-armed-conflict-rohingya.pdf pg 20

- [2] http://www.hrw.org/reports/2000/burma/burm005-02.htm

- [3] http://www.amnesty.org.au/refugees/comments/35290/

- [4] http://www.hrw.org/news/2015/01/13/burma-amend-biased-citizenship-law

- [5] http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/no-end-in-sight-to-the-sufferings-of-the-worlds-most-persecuted-minority–burmas-rohingya-muslims-8202784.html

- [6] Human Rights Watch, Burmese Refugees in Bangladesh: Still No Durable Solution, Vol.12, No.3 (c), May 2000

- [7] http://www.rsc.ox.ac.uk/files/publications/other/dp-children-armed-conflict-rohingya.pdf pgs 21-78

- [8] As told in Greg Constantine, Exiled to Nowhere. Burma’s Rohingya, 2012, part of the Nowhere People book series

- [9] http://www.rsc.ox.ac.uk/files/publications/other/dp-children-armed-conflict-rohingya.pdf pgs 11, 13 and 23

- [10] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dSkZlgk76-E (Al Jazeera Investigates documentary)

- [11] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5sK0h7Zqs3k (BBC News)

- [12] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7ltddmZlnmQ

- [13] http://world.time.com/2013/06/20/extremist-buddhist-monks-fight-oppression-with-violence/

- [14] http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,2146000,00.html

- [15] http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-32740637

- [16] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mECzWtqFV9E

- [17] http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-32740637

- [18] http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/may/21/nope-nope-nope-tony-abbott-says-australia-will-take-no-rohingya-refugees

- [19] http://www.reuters.com/article/2015/06/01/us-usa-myanmar-obama-idUSKBN0OH37C20150601

- [20] www.muslimnews.co.uk/newspaper/top-stories/persecution-of-rohingyas-in-myanmar-is-genocide-say-nobel-peace-laureates/