Quilliam addressed those gathered in a speech in which he emphasized the need for peaceful Muslim-Christian coexistence and the need for Muslims to educate themselves in both Islamic and worldly disciplines.

Quilliam addressed those gathered in a speech in which he emphasized the need for peaceful Muslim-Christian coexistence and the need for Muslims to educate themselves in both Islamic and worldly disciplines.

In 1894, the Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II decided to present his empire’s highest civilian order to Muhammad Shitta, a Nigerian Muslim entrepreneur from Lagos. Shitta earned the honor by sponsoring the construction of the mosque in Lagos. This was a time during which European missionaries, who had followed Europe’s colonial powers in their “Scramble for Africa” in recent years, were very active in trying to spread Christianity in West Africa.

Perhaps the sultan wanted to challenge this activity; maybe he also wanted to spread the influence of the struggling Ottoman Empire in faraway Muslim communities. However, the sultan wasn’t personally able to go to present the honor to Shitta; so he chose W.H. Abdullah Quilliam, a British convert to Islam, to go on his behalf. After embracing Islam in the late 1880s, Quilliam had played a leading role in organizing the small Muslim community in Britain.

Within a few years of embracing Islam and travelling in North Africa, Quilliam had earned the title of ‘alim (Islamic scholar) from the very prestigious University of al-Qarawiyyin. He had also earned the admiration of the Ottoman sultan, who (as the nominal caliph of the Muslims) had named Quilliam the leader of the British Muslims.

Responding to the Sultan’s request

On June 6, 1894, Quilliam departed from Liverpool, England to begin his journey to Lagos. On the way, he stopped at the Canary Islands, Senegal, Gambia, Sierra Leone, Liberia, and the Gold Coast before finally arriving in Nigeria. He was guided along the way by West African contacts he had made through his role as a Muslim journalist and leader in Britain. The influence of the British Empire at the time had made Quilliam something of a celebrity among Muslims around the world.

Everywhere he stopped, crowds gathered to see and meet him. Since the West African Muslims were generally black, many of them were encountering a white Muslim for the first time. When he met an elderly blind Imam in the Gambia, for example, the Imam rubbed his hands over Quilliam’s face and tearfully said, “I have now heard the voice and been in the company of the White man who is preaching the true faith of God and His Prophet to the great English nation, and now Allah, the Most Merciful and Compassionate, your servant is ready to depart this life in peace, whenever You shall call him home, for his ears have listened to the voice you have inspired to be the revealer of the truth to the white men, and to be the proclaimer of Islam in the midst of its enemies.”

The Grand Opening of a Mosque

On June 28, Quilliam finally arrived in Lagos, where he was welcomed by thousands of Muslims and non-Muslims. In the company of his friends Al-Hajj Harun al-Rashid, who had recently visited him in Britain, as well as Shitta, the recipient of the Ottoman honor, Quilliam spent the next few days preparing for the opening of the new mosque, known today as the Shitta Bey Mosque. The mosque was special in that it had been sponsored by Shitta and it had been designed by two black Muslims who had returned to Nigeria from Brazil, where they may have once been taken as slaves.

Thus, the mosque was designed, built and paid for by black Muslims, and it was symbolized that Islam was now firmly rooted in West Africa.

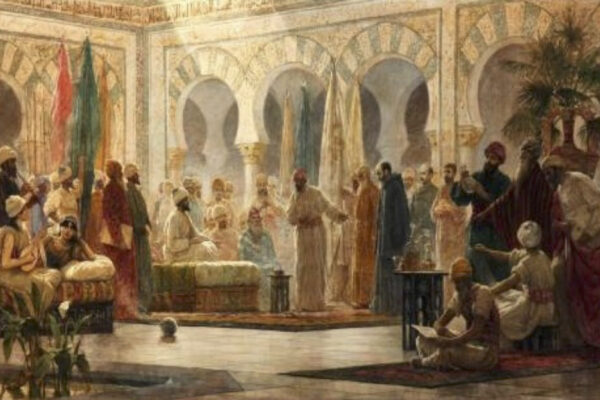

The grand opening of the mosque was on July 5th. The ceremony was attended by Muslims from across West Africa. Even non-Muslims were present, such as Quilliam’s good friend Robert Blyden, the father of the ideology of pan-Africanism. Shitta was duly honored, after which he became known as Shitta Bey (“bey” being a prestigious Ottoman title).

Islam is Beyond Culture and Ethnicity

Quilliam addressed those gathered in a speech in which he emphasized the need for peaceful Muslim-Christian coexistence and the need for Muslims to educate themselves in both Islamic and worldly disciplines. Quilliam doesn’t seem to have offered this advice in a patronizing way to his West African brothers and sisters; rather, as they recognized, he genuinely wished to help them address the problems they faced and had expressed his affinity for Africa, long before he had been sent on this mission by the Ottoman sultan.

Having completed his mission, Quilliam set off on his journey home in late July. He was suffering from malaria and special prayers were made for his recovery after the Friday congregation across West Africa. After his return to Britain, Quilliam and many West African Muslim leaders, including Shitta Bey, remained in very close contact. Quilliam’s newspapers, the Crescent and the Islamic World, helped news about the Muslim communities in West Africa spread regularly across the Muslim world; meanwhile, Quilliam and his writings became very popular in West Africa, and one Christian man even claimed to have embraced Islam after just reading Quilliam’s The Faith of Islam.

However, the aspect of this interaction for everyone involved in it was that it could be said that, without denying the importance of race to a Muslim’s identity, “Islam transcends race and eliminates racism” was not just a lofty ideal but an achievable reality. Black Muslims had wholeheartedly embraced a white Muslim, and vice versa, and this was a first-time experience for many. A Muslim leader of the time from Sierra Leone, Muhammad Gheirawani, said it best:

“We were often told [by European colonialists]… that Islam was the religion only of inferior races—that it could be received only by the black man. Ah! What will they say now when great Englishmen are bowing down under the rays of the crescent?”

References:

- Brent D. Singleton (2009) “That Ye May Know Each Other”: Late Victorian Interactions between British and West African Muslims, Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs, 29:3, 369-385.

This article was originally published here on iHistory.