“Yes, it is possible to be black or brown, sing the national anthem of one’s European country, and to take a knee against racism. But if the national anthem in question celebrates a nation that has never atoned for its colonial — and therefore racist — history, doesn’t the audible gesture of singing it completely undermine the visible gesture of antiracist kneeling that follows?”

“Yes, it is possible to be black or brown, sing the national anthem of one’s European country, and to take a knee against racism. But if the national anthem in question celebrates a nation that has never atoned for its colonial — and therefore racist — history, doesn’t the audible gesture of singing it completely undermine the visible gesture of antiracist kneeling that follows?”

“This is the way the world ends, not with a bang, but a whimper.” So goes the famous closing line of T.S. Eliot’s poem “Hollow Men”, but for the English men’s football team and the nation that vicariously lives through it, it was the other way around: their world came crashing down not only in a botched penalty shoot-out in front of a packed Wembley stadium that handed Italy the championship title (deservedly), but also in the aftermath of the defeat when the three players who missed their shots, Marcus Rashford, Jadon Malik Sancho and Bukayo Saka (all three of them black), were inundated by a deluge of online racist abuse from disgruntled “fans.”

Not only was the pandemic-delayed Euro 2020 one of the better tournaments in recent years, with plenty of drama (heart-stopping penalty shoot-outs, real hearts actually stopping on the pitch), displays of individual and collective artistry (Kylian Mbappé’s and Lorenzo Insigne’s elusive dribblings, La Furia Roja’s cautionary return to the Tiqui-taca of its glory years) and mind-boggling plot twists (defensive Italy playing attacking football? Tiny Switzerland knocking out La Grande Nation?? England knocking out Germany???), it was also the most politicized in recent history, with LGBTQ+ rights and racism being the dominant issues, as evidenced by the prominent displays of rainbow flags in the stands and on sponsor logos as well as the Kaepernickian knee-taking before kick-off respectively.

But next to the twin outpourings of commiseration in the wake of Danish striker Christian Eriksen’s on-pitch cardiac arrest and EU-member Hungary’s homophobic legislation, the political gesture of kneeling for Black lives and against racism did not quite manage to capture the imagination of many a white fan or the undivided attention of the mainstream media. This also had to do with an ultimately racist white fragility that sees anti-racism as an insult (like many English fans did when they booed their own kneeling players), as well as with the deficient way this well-intentioned gesture was performed.

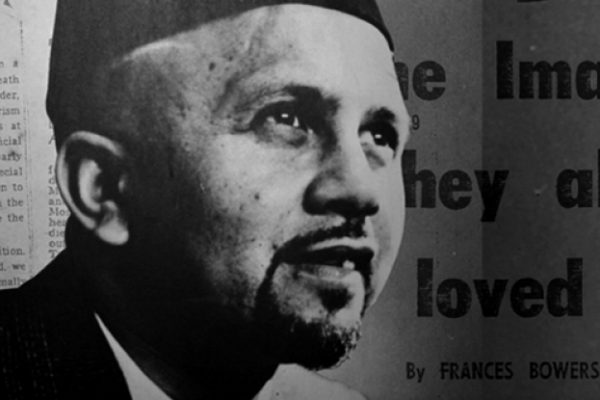

Why players taking the knee were no Kaepernicks

The protest and solidarity gesture of “taking a knee” that was spearheaded at Euro 2020 by multiethnic teams such as England, France, Belgium, and the Netherlands and emulated at times by not so diverse teams based on everything from true conviction and allyship (e.g. Scotland), opportunism (e.g. Germany) and peer pressure (e.g. Austria and Denmark), was on the one hand widely supported by anti-racists, while on the other hand harshly criticized by anti-anti-racists, such as Britain’s “janissary of empire” Priti Patel, to use a wonderfully succinct term by British-Pakistani author Mohsin Hamid to describe the breed of the brown-skinned “bootlicker”, which Urban Dictionary in turn defines as “when an oppressed person…sucks up to the oppressor in hopes of appeasing them.”

Remember that Ms. Patel has in the recent past famously described Black Lives Matter as “dreadful”, and the booing crowds of white fans and the white squads demonstratively taking a counter-revolutionary stand while their opponents were taking a knee did their part in trying to fight humanity and humility with loud and quiet antagonism.

But let’s be honest: what was framed as a bold show of protest by media creators and consumers alike, borrowed from African-American former NFL football player Colin Kaepernick, was despite all its good intentions an epic fail. Remember, Kaepernick took his knee during the rendition of the U.S. national anthem, not after it. He solitarily knelt there on the pitch from start to finish, and was mercilessly booed for it by white stadium-goers throughout the entire anthem. But his resolve never wavered, and he kept kneeling his ground, so to speak, throughout the rest of the 2016 season, which would turn out to be his last after being ostracized by the league for his signature political protest against police brutality and racial injustice.

Kaepernick voluntarily sacrificed his athletic career for a greater cause, subordinating any fear of personal consequences to the onus of open revolt against systemic inequities. What the protesting players of European football at Euro 2020 did, on the other hand, sacrificed little and was far from a revolt: too cowardly? to take a knee during their national anthem, they chose to do it in the ridiculously short time frame between the coin toss and kick-off. And they even failed to do that consistently and convincingly: at some matches, all the players of a team knelt, at some only an assorted few. And most of the time those who did kneel did so in such a hurry to get it over with that it was painful to watch, their body language displaying awkwardness and fear rather than resolve and courage.

No, the taking of the knee at Euro 2020 was tentative at best, utterly farcical at worst. It definitely did not deserve to be ridiculed as “wokeness politics” (UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson), or mercilessly booed, but it did not deserve overt praise either. For the gesture to have mattered and have transcended the boundaries of performative activism, it should have been executed more confidently and risen above an at times haphazard choreography lacking in devotion to the cause, its primary angle of effortlessly trying to increase one’s social capital visible from the outset.

When national anthems are colonial anthems, and the colonized are expected to sing them

Remember when Black, Brown, and Muslim players of Western European teams would keep their mouths shut during the pre-match renditions of the national anthems? Zinedine Zidane and Karim Benzema of France, Mesut Özil and Jerome Boateng of Germany: their silence spoke volumes about colonial histories and racist presents, palpable their desire to not morally elevate the racist nations they grew up in by singing their praise.

Unfortunately, those halcyon days of low intensity, yet high-value anti-racist protest seem to be over: pretty much all BPoC (Black, People of Color) players of multiethnic teams at Euro 2020 (even Benzema, following his reinstatement into France’s national squad, could be seen mouthing along the Marseillaise) seemed to have surrendered to the dictates of having to prove one’s patriotism by assimilating into the white-majority culture of their home countries, of which the uniform bawling of the national anthems of former colonial powers or/and of systemically xenophobic nation-states at sporting events is its most visible and audible manifestation.

Don’t get me wrong: there are enough non-political reasons for players to not sing their national anthems: they might simply not like the song, they might be terrible at singing (Gary Linker, by his own admission), or they might not know the words (Wayne Rooney). But players of an ethnic minority background don’t exactly have the white privilege of being callous: when they wear the jersey of their white-majority country and don’t sing praise to the nation, white hegemonic discourse tends to frame their refusal as an act of treason, further corroborating the legitimacy of said reluctance.

The lyrics to national anthems are typically heavy with history and often ridiculously outdated: when the Dutch “Elftal”, the earliest example of an ethnically diverse Western European football squad, sing “Het Wilhemus”, of which the first line goes: “Wilhelmus van Nassouwe ben ik, van Duitsen bloed” (William of Nassau am I, of German blood…don’t tell the Germans, they’d have a field day with this juicy bit of intel about their biggest football frienemy), I can’t help but marvel at the continued presence of the outrageously anachronistic concept of a bodily fluid having a nationality.

Despite “German blood” never having been a thing (according to the International Society of Blood Transfusion, there are 38 different human blood group systems, none of them going by the name “German”) and the scientific consensus of today being that ethnicity is more of a social construct than a biological marker, I wonder what it must feel like for a Dutch footballer, raised on a steady diet of cultural anti-Germanism, proclaiming how proud he is of his German blood!

And what about those players of Surinamese or Curaçaoan descent singing a song praising the past glory of the Dutch crown, the legal successor of the Dutch West India Company that colonized the lands of their forebears, who themselves were forcibly brought to that part of the Caribbean in the Atlantic slave trade to toil on plantations where they were treated so barbarically even by the standards of the time that British historian C.R. Boxer in his book “The Dutch Seaborne Empire” wrote “man’s inhumanity to man just about reached its limits in Suriname?”

Do Gigi Wijnaldum and Patrick van Aanholt, Denzel Dumfries and Donyel Malen not know their history?

Lukaku, Leopold II and the “burden of history”

As equally ignorant one could describe the case of the son of Congolese parents singing the national anthem of Belgium, like its Dutch neighbor a tiny country that once wielded a power utterly disproportionate to its size and that somehow managed to secure one of the largest swaths of territory on the African continent for its King, Leopold II, who’s colony of the Congo Free State (a lie of a name if there ever was one), was actually a private estate designated exclusively for resource theft. An estimated 10 million Congolese men, women, and children were worked, killed, and tortured to death there out of nothing other than proto-capitalist avarice and white supremacist sadism, in the context of which the term “crime against humanity” was coined.

But regardless of all this, Lukaku appears to have no qualms whatsoever about singing the trilingual “La Brabançonne”, of which the current lyrics date back to 1861, four years before Leopold II ascended the throne, and of which the two last lines are “For King, for Freedom and for Law. For King for Freedom and for Law.” Lukaku would do well to get woke to what Sudanese author Tayeb Salih in his anti-colonial novel “Season of Migration to the North” from 1966 described as “a bottomless historical chasm separating the two”, namely the colonizer from the colonized, the Global South from the Global North: a divide so wide that it takes more than the rendition of colonial anthems on football pitches in front of stadium-goers and a global TV audience to bridge it.

Where is the wokeness after Windrush?

As revisionist to boot one could classify England’s Black players singing “God Save the Queen”, a ditty so outdated in its unquestioning idolatry of empire and the blood-stained history of the monarchy as is the institution itself, making one wonder if the lyrics would have been more historically accurate had they gone “God save us from the Queen.”

“Gracious” and “noble”, “happy” and “glorious” are the bullet-point adjectives sprayed through the first verse: that’s one way to whitewash one’s genocidal past. Even better when one’s black subjects — coopted by bestowed low-level knighthoods and blinded by the chimera of inclusion as evidenced by people of color having been allowed to enter the highest echelons of Western political power, the Sadiq Khans and Sajid Javids, the Priti Patels and Rishi Sunaks—are doing the dirty work of historical falsification for you by praising the racist and criminal history of your family through song.

One would have thought that the 2018 Windrush scandal, when it came to light that British people of Caribbean origin had been falsely detained, denied legal rights, and had even been wrongly deported, would have sensitized English players of Jamaican heritage like Kyle Walker and Raheem Sterling — two stand up guys on and off the pitch by the way — into a more critical attitude toward the imperial anthem of the country that came and conquered their ancestral lands through organized, white supremacist bloodshed.

But undoing one’s self of the “burden of history”, as British author Zadie Smith put it in her tragicomic debut novel “White Teeth” which tells the story of the British immigrant experience from a Jamaican and Bengali Muslim perspective, by singing a song that praises a nation and its regent family that played a large part in putting that historical burden upon you in the first place might be more Stockholm syndrome and masochism than sustainable mechanism of coping with the past.

Yes, it is possible to be black or brown, sing the national anthem of one’s European country, and to take a knee against racism. But if the national anthem in question celebrates a nation that has never atoned for its colonial — and therefore racist — history, doesn’t the audible gesture of singing it completely undermine the visible gesture of antiracist kneeling that follows?

Furthermore, it would be interesting to see if the allyship extended by white players to the targets of racist abuse would pass the litmus test of their teammates refusing to sing songs that can only be described as insulting and triggering to hear if you are Black or a person of color and add further insult to injury once players are expected to sing them. And should they fail to do so, they are symbolically banished from the “nation” (which Benedict Anderson famously exposed as a mere “imagined community”), as Mesut Özil was by white Germany.

With the World Cup in Qatar, the first-ever in the Muslim world, being only a year and a half away, the racist bullying of Rashford, Sancho, and Saka as the latest high-level incident of ugliness within the “beautiful game” should coax all BPoC players and their white allies from every national team into rising above the performativity of poorly executed gesture politics and finally becoming true, fearless agents of social change, no matter the risk to their careers.

Colin Kaepernick, who is already known more for his Civil Rights activism than he is for his footballing, did what he felt he had to do, and the world is already a better place for it.