We are not British despite our culture, we are British and we are contributors to the culture.

We are not British despite our culture, we are British and we are contributors to the culture.

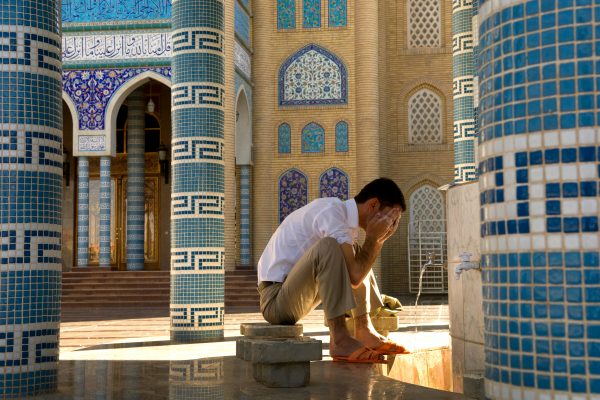

This Christmas season has been a strange one for me. I live in Birmingham, which is 20% Muslim and very diverse, I work with predominantly white colleagues and socialise with a mixture. This year, my little family (wife and two kids) have been invited to a Christmas Milad celebration on Christmas Day, a strange combination which will undoubtedly involve Quran recitation before Secret Santa, as well as Crackers and maybe even a tree. Traditional Christmas Dinner will be spiced up because some things you just don’t mess with.

Brown people will be asked if they ‘celebrate Christmas’ from work colleagues, classmates, and well-meaning strangers multiple times this month. It falls into a category of ‘awkward but less-awkward-than-not-mentioning-it’ questions that come with the season for people who aren’t white. It’s joined by the hesitation around ‘Merry Christmas’, and invitations to Christmas parties and Christmas Jumper Days (‘does s/he have one? Are they allowed to wear that?’). It’s not a universal experience by any means. It’s possible to act white enough all year round to evade all awkwardness, or simply live in the bubble that is London.

My own muddled celebration of the season and confusion around heritage, identity, and parenting was highlighted, even exacerbated, by a post I came across on Facebook a couple of days ago. A popular Islamic Scholar asked his Facebook fans, acting seemingly surprised, if Christmas Trees were actually a thing amongst Muslim families. The responses varied, from outraged religious Muslims, demanding these practices be addressed and wiped out, devout worshippers very sad about this turn of events, interfaith activists inviting Muslims to celebrate in a more acceptable way (with Christians. And purpose), and perplexed celebrators wondering what the big deal is. One person even attributed it all to the “Western Conspiracy” to defeat Islam.

In Britain, most Muslims participate in traditional British cultural practices, even those with explicitly Christian origins. During Christmas, three-quarters (73%) send cards and three in five give presents, and many also send Mother’s Day or Father’s Day cards and wear a poppy on Remembrance Day. Most, however, do not put up a Christmas tree.

I’m not particularly interested in the religious questions around how God views Muslims celebrating Christmas (Vir Das on Netflix has a few thoughts – ‘Chrislam’ anyone?). But I am interested in the divergence of practices amongst Muslims from similar communities with similar beliefs. In particular, amongst immigrant communities in the UK (yes, I mean you Mr. ‘I’m a British citizen of Indian heritage’).

I don’t mean to discount religious beliefs around the issue, but instead, I mean to reframe the question. In migrating from Muslim-majority (or large minority) countries, it seems imperative to me that we should attempt to understand the identity crisis of second and third generation immigrants and the impact of educational environments, domestic political activity, multiculturalism, foreign policy and war, and social attitudes. I mean to ask the question: what will hold our communities together in generations to come, if anything?

Religion is the obvious answer still, even after reframing the question. And it has always been the answer from Muslim immigrants in the West. From Muslim majority countries, 68% of Muslims said they view Westerners as selfish or other negative attributes: violent (66%), greedy (64%) and immoral (61%), while far fewer had positive things to say: “respectful of women” (44%), honest (33%) and tolerant (31%).

It’s only natural, given that view, that first generation immigrants will take steps to protect their families from being dominated by their host culture. The only problem is, it hasn’t really worked. Around half (49%) of Muslims say they would like full integration with non-Muslims in all aspects of life, with younger Muslims and those born in the UK more likely than older Muslims and those born abroad to support this.

I don’t really care either way whether or not you put up a Christmas Tree. I’m generally of the “live and let live” philosophy. But I do feel a sense of loss with regards to my community and heritage.

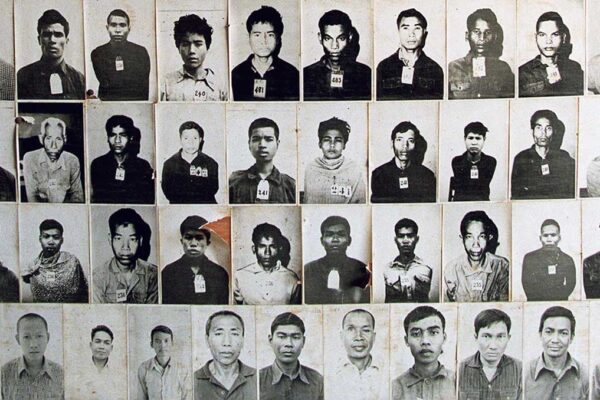

Historical events have conspired with the current state of our society to promote assimilation above all else, and to label it as multiculturalism. To celebrate diversity, as long as it is skin deep. To admonish racism, as long as it’s blatant, overt racism, rather than structural inequality. White privilege is more evident than it has ever been, and the acceptance of its reality by non-whites is lower than ever.

The positive narrative around immigration (in that it enriches our society) has subtly changed because of the sustained attack it has received. Suddenly, it has become important to form an economic defense (immigrants actually add value to our economy), a social defense (don’t be silly, they’re just like us), and a political defense (we bombed them). The reality is, western societies have been thoroughly enriched by foreign culture – from curry to yoga to tea – but usually on their own terms and with little or no credit. On the flip side, many foreign cultures were pillaged and trampled over by colonial powers.

We are not British despite our culture, we are British and we are contributors to the culture. Muslims come from a rich heritage in academia, medicine, arts, music, food, fashion, and spirituality and we should be thanked for it, not be apologising for it. The life of this culture only lives as far as it is kept alive in our communities, or it risks being colonised in its own way: absorbed in diluted forms of British practice, with no credit or cultural memory.

If that’s not enough, there’s another very important reason to make sure our communities survive: minority communities lack power in every way imaginable. I mentioned 20% of the population of Birmingham identifies as Muslim: of these, 75% live in poverty. Minority communities are hugely underprivileged, and in many cases under direct attack. However, race is not the only divider in our society. A more obvious, more established example is class. There are lessons to be learnt from how the working class have fought their battles: by coming together.

Whether it’s to keep our cultural heritage alive or to unionise, our community centres and practices are important. The question remains: In an age that is seeing an increase in the plurality of religious beliefs and practices, what will hold our communities together? What will appeal to my daughter and motivate her to be involved in the community?

Part of the answer has to lie in the richness of our culture itself. If it’s not appealing enough, is it even worth preserving? The idea that religion has to be monocultural, or that it is somehow incompatible with cultural practices that aren’t religious will not survive the test of divergence in belief. A less dogmatic view of religion, with an emphasis on culture, will be far more likely to ensure that our spiritual heritage is preserved.

I don’t know the whole answer. I do know that if we as a community continue to practice intolerance towards any form of diversity in belief, we become the perpetrators of our own downfall. If we are able to look beyond that, we can begin to ensure the legacy lives on and empowers the generations to follow.

Sources

Ethnic Minority British Election Study, 2010, 1,140 GB resident Muslims aged 18+ belonging to defined minority ethnic groups and not living in low penetration areas

ICM Survey of Muslims for Channel 4: interviews with 1,081 Muslims aged 18+, conducted face-to-face across Great Britain on 25 April-31 May 2015, and with a nationally-representative control group of 1,008 adults aged 18+ by telephone on 5-7 June 2015