Is this a befitting state for anyone to live in?

Is this a befitting state for anyone to live in?

Honoured to visit Mumbai, India to recite the Ashra (ten days) commemorating the revolution and martyrdom of Imam al-Hussain (as), I requested to visit Govandi, a neighbourhood in east Mumbai, one of the worlds largest slums, or Jhopadpatti in Hindi. My lecture series included topics on how Islam tackles poverty,[1] the necessity of resolving the global water crisis and the urgent need for a clean and sustainable environment.[2] Amongst the key points made was that today, eight men (some say six) own more wealth than half of the entire world. This is in explicit contradiction to the economic principles of Islam when the Qur’an proclaimed that wealth must not restrictedly circulate amongst the wealthy by “going round and round such of you that already be rich.” [59:7]

Reading scholars like Joseph E. Stiglitz, Jeffrey Sachs, Kathryn J. Edin and Mohammed Baqir as-Sadr on extreme poverty and just economic systems wasn’t enough. Having spent time in similarly impoverished areas of Iraq, I wanted to appreciate and understand the plight of the Indian community, with whom I share ancestry just two generations back, as well as speaking about it. This could only be achieved by meeting those in desperate poverty and listening to them.

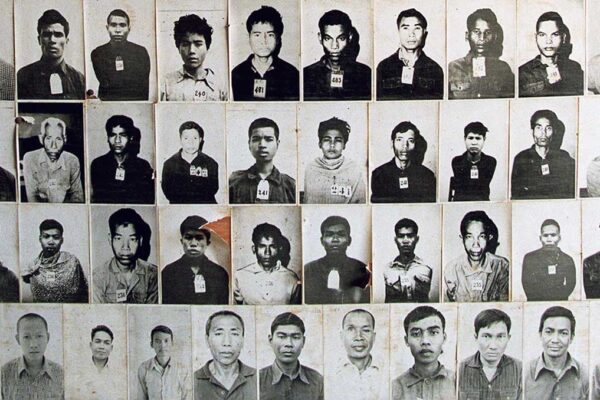

Below are some of the pictures I took (with the permission of the locals/those in the pictures), accounts of what I saw and experienced and commentary from my guides. I will begin with a brief context to poverty in India and Govandi. The goal behind this article is simply to ask the respected reader to reflect on whether this is a befitting state of humanity in 2017, to query our personal buying practises and wastage, and whether we contribute to this state of deprivation through our political and economic choices.

Poverty in India and Govandi

According to British economic historian Angus Maddison, at the beginning of the eighteenth century India accounted for 23% of the worlds economy, which is equal to all of Europe. When the British ended its colonisation in 1947, this had dropped to 3%. Shashi Tharoor[3] details how the pillage of India was solely for the benefit of Britain destroying its industries, plundering its natural resources, enforcing extortionate taxes, overseeing numerous famines and decimating its social systems, thereby crippling its people. Britain even used millions of Indian soldiers in successive World Wars, only to then tax them for the privilege of dying for Queen and Empire. Upon departure, Britain left just 8% of the population employed in modern industry. Minhaz Merchant estimates reparations would be in the region of $3 trillion.

Subsequent misrule and corruption by the ruling Congress Party resulted in neglecting education, malnutrition and infrastructure, nurturing India’s new found poverty; poor preparation for the trebling of its population to 1.3 billion people, lack of local governance, gender inequality and over investment in ‘defence’ and nuclear weapons post partition advanced it. Since 1991 however, India saw rapid economic growth, transforming much of its urban areas. Despite this in 2011, India, with 17.5 of the world’s population, had 20% of the world’s poorest people, many of them living in rural areas, villages, or slum towns, like Govandi. This figure counts only those in the most abject of circumstances, the desperately poor. In fact, more than half the country lack means to meet their basic needs.

Nearly half the world, 3 billion people, live on less than $2.50 a day. More than 1.3 billion people live in extreme poverty, on less than $1.25 per day. That means everything from food, drink, clothing, shelter, travel expenses, gas, electricity and educational material is within this daily budget. The residents of Govandi live in such circumstances. Govandi is home to hundreds of thousands of people. Infant mortality is 55 out of 1000 and more than half of children have stunted growth due to malnourishment. One in three girls, and one in five boys are illiterate.[4] It also has the worst air pollution in Mumbai.[5] Cumulatively, the area’s shanty towns have the lowest human development index in the city at 0.05.[6]

Heading to the slum town, Govandi

Bandra, an affluent part of Mumbai where I was – thanks be to God – staying, is a ten minutes drive to Govandi. Mumbai has several slum areas: Malavni to the west of the city, Dharavi (made famous by the film Slumdog Millionaire) to the north and Govandi to the east. As you depart one area for the next, you see modern houses literally next to dilapidated ones. My guide tells me, “This is so these houses serve each other in providing labour and work close by.”

To reach Govandi you must cross the Bandra Kurla Complex, host to the financial district. Most prominent to me was the Bharat Diamond Bourse, the worlds largest diamond exchange, another vivid example of the stark contrast before me.

Entering Govandi

On approach to Govandi, you begin to see rows of jewellery shops. I’m informed this is because most residents do not have a bank account and so it is safer to wear cheap jewellery than store cash. Also, the jewellers serve as loan sharks, or what the West might refer to as ‘Pay Day Loan’ companies, charging ridiculous interest rates.

In the distance is an International Baccalaureate (IB) school and a housing complex. My guide tells me the government stipulated social housing must be built by the foundation in exchange for access to the location, but that the housing was built on the cheap, devoid of proper insulating materials.

Our taxi drops us at the edge of the neighbourhood where we meet resident and aid worker Qari Mojiz Abbas Rizvi, my second guide. Mojiz runs an office registering residents with official documents, supporting job searches, documents local needs, and collects and distributes aid.

As we start our walk, Mojiz narrates the history of Govandi. It was originally a giant trash pile, divided by some hills. The impoverished of the city moved in, at times, literally living on the pile. In my head, I am reminded of Paulo Freire’s recounting of the horrendous conditions in the slums of Brazil that lead to one family scavenging a similar landfill to eat “pieces of an amputated human breast with which they prepared their Sunday lunch.”[7]

The Shanti Nadhr Quarter

The first area of the visit was to the community of Shanti Nadhr, loosely translated as ‘The Peace Colony’. What struck me was the apparent displays of faith. Banners hung on every street and echoes of sermons from speakers rang through the narrow alleys. We visited several houses and listened to families struggling to find work, pay medical expenses and make requests for assistance.

One family we visited, their house of only one room (as was nearly every house we visited) comprised of one brick wall, and the remaining three walls and roof made of sheet metal. A dim light shone on a curtain dividing the house in two, the far side where the middle-aged mother slept and the front where the children stayed. She and her son, a delivery driver, explained that in the rain, water leaks in and in the summer, unbearable heat is trapped in the metal room. There is nothing more than a fan to circulate the heat.

The son and his family had another house close by. The rent of his mother’s house was approximately £50 per month while the family income was £130 per month. When asked what she needed, the mother replied that even if she wanted to move she couldn’t, because landlords charged such expensive deposits, that she does not have such a lump sum. If this money could be raised, she could think about somewhere better for her family.

As we leave Shanti Nadhr, I notice several offices of politicians in the area, each offering promises of hope, clambering for the local vote. We take a tuk-tuk to the next, far poorer, area.

The Rafique Nagar Quarter

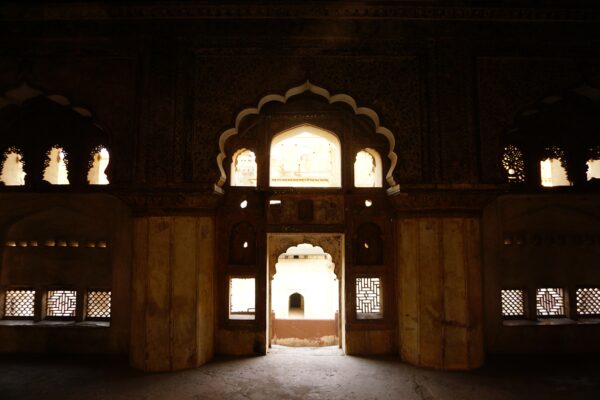

We tour the Rafique Nagar area, built upon mounds of mud and around wastewater holes, littered with debris. Shacks have bamboo sticks as their structural supports and sheet metal, plastic and tarpaulin as walls, flooring and roofing.

From time to time we see semi built or destroyed houses. I am told that periodically the government enters and demolishes large numbers of the makeshift cabins as residents here are squatters and illegal building is not tolerated. I ask where do residents go, to which I am informed they either rebuild in another part of the slum or leave in search of anywhere else to stay. This cycle across the country is a factor for internal displacement and movement.

Child labour and dressmakers

Moving between the houses, our guides tell us about the economy in this area. Many men and women make the Indian dresses that end up in shops, both locally and internationally, as wedding outfits, saris, shalwar kameez and lengas. This is known as Zarii work.

Agents bring the material, trim and sequins and pick up the finished product. Depending on the weight and difficulty of the dress it can take anywhere between three and fifteen days to make one dress, working up to 14 hours per day. The pay is set at 200 Rupees (£2.30) per day and workers are given limited time to finish the job. For this reason, the children often have to work to help finish the dress in time. The children do not earn money for their participation as pay is set for one day of work, irrespective of how long it may take, how many workers it requires or how much it sells for.

I am told it is not unusual for the dresses made here to be sold in the Mumbai markets for 25,000 Rupees (£290). As we leave this area, I wonder how many of the dresses in London, Birmingham, Leicester and Manchester have been made here.

The Baba Nagar Quarter

We reach the Baba Nagar area, lively and bustling, another contrast to the quiet, labour intensive district from before. We’re shown different types of local economy including carpentry and grocers. There is a procession or Juloos to be held later that day, in honour of Imam al-Hussain (a) and people are busy preparing food to be given out in his remembrance. I recall being amazed at such poverty, yet such commitment to charity by the very same needy people!

We walk past the local Mosque, Masjid Bismillah, where all sects of Muslims gather and worship together.

Visiting the local aid trust

Mojiz leads us to his office and shows us the computer register of literally thousands of people dependent on various types of financial support. Each family and person is given an individual identification number and their details recorded including income, requests and distribution history.

He provides examples of the records for the types of distribution he oversees. One is a month’s food supply at the cost of 4000 Rupees (£46) and the other is subsidies for a child’s education, books, equipment and school fees for the year at 7000 Rupees (£81). He also mentions that subsidised college education ranges from 12,000 to 25,000 Rupees, depending on the quality of the college.

Water waste channels and rising sewage

Our penultimate stop is to visit more families, but this time those closest to the water and waste outlets. Most houses do not have indoor plumbing. Where possible electricity is rented or appropriated. Most streets have endless piping through them, draining out the waste from makeshift toilet and shower facilities, each with long queues of people waiting patiently.

These pipes often lead out toward large pits in the middle of huddled communities. In the rainy season, these pits often rise and swell. The shacks surrounding them have no way to stop the sewage entering the shacks, bringing with it human waste, disease and debris.

One of the dwellings we visited, again being one roomed, housed a mother and her six children. She told us paving slabs had recently been donated, providing her with a flooring above the mud. At the back of the room, as can be seen in the picture, the mud was falling away risking the foundations of the entire house, the sewage pits a few meters away.

Heading home

In total, we had spent maybe four hours exploring. Almost everyone we spoke to had a glimmer of hope in their eyes that we would help them. As we departed following afternoon prayers, we saw more centres of distribution in the name of Imam al-Hussain (a), this time giving away free water, known as Sabeel. It was a fitting way to end the visit, reminding us that although impoverished in one way, they were beyond rich in another.

Conclusion

The reality is, all of what we saw was by human design. The majority of the world has decided to cultivate, propagate and export this economic system either in its recent history or present. This system is entirely man-made and to the benefit of a few. What’s worse is the economic systems we rely upon are structured in such a way that our advertising, banking, international markets and purchasing only reinforces this systemic poverty.

In a famous narration, Ja’far as-Sadiq (as) states,

“Zakat (almsgiving and charity by which purifies the wealth) has been ordained as a test upon the rich and a means of assistance for the impoverished. Had people given their Zakat there would not remain a poor, needy Muslim. Certainly, people are not impoverished, not in need and not left hungry except because of the evil actions of the rich. And it is the right of Allah to prevent His mercy from the one who prevents the right of Allah in regard to his wealth. And I swear by the One who created creation and spread its sustenance, that no wealth is truly lost in the land or in the sea, except by turning away from giving Zakat.” [8]

You will note that in no place am I seeking to push a charity or seek donations. All I seek from myself and the respected reader is to spend some time thinking about whether this is a befitting state of humanity and in which ways do we actively contribute to this state, either by our spending, our waste or our political choices.

[1] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dHl-1PmXQvA

[2] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o1PfPX6vocY

[3] An Era of Darkness. The British Empire In India, Aleph Book Company

[4] https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/mumbai/57-children-stunted-in-mumbais-govandi-slum-survey/articleshow/56551631.cms

[5] https://news.vice.com/article/this-slum-has-the-worst-air-pollution-in-mumbai

[6] http://www.dnaindia.com/locality/mumbai-north-east/report-meast-ward-reveals-poor-picture-mumbai’s-unequal-development-58740

[7] Pedagogy of the Oppressed, 30th Anniversary Edition, Introduction

[8] انما وضعت الزكاة اختباراً للاغنياء ومعونة للفقراء، ولو انّ الناس أدّوا زكاة اموالهم، ما بقي مسلم فقيراً محتاجاً ولاستغنى بما فرض الله له، وان الناس ما افتقروا ولا احتاجوا ولا جاعوا ولا عروا إلاّ بذنوب الاغنياء، وحقيق على الله تبارك وتعالى ان يمنع رحمته ممن منع حق الله في ماله، واقسم بالذي خلق الخلق وبسط الرزق انه ما ضاع مال في برّ ولا بحر إلاّ بترك الزكاة…