In short, our brains are wired to deify something. As Muslims, we are blessed to recognise the One and Only Deity worthy of worship, Allah, exalted be He. For those who do not deify Allah, they will seek to deify something else.

In short, our brains are wired to deify something. As Muslims, we are blessed to recognise the One and Only Deity worthy of worship, Allah, exalted be He. For those who do not deify Allah, they will seek to deify something else.

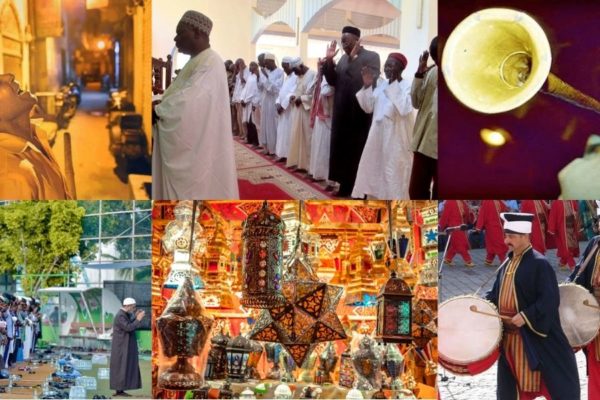

Islamic institutes have long been a centrepiece of Muslim communities, whether they be mosques, centres of learning, or Sufi lodges. These institutes have in the past actualised Islamic ethics in a physical space, lending a sense of tangibility to Islam’s spiritual edicts. In the secular environments that Muslim communities have recently found themselves in, the process of institution building is ongoing. Or, at the very least, the process of building institutes that fulfil a Muslim’s spiritual needs is still ongoing. As obvious as this sounds, we can use insights from Jungian Psychology to further understand the consequences of a lack of such institutes.

Jungian Psychology is based upon the ideas of Carl Gustav Jung, the 20th-century Swiss psychiatrist. He is generally seen as the father of analytical psychology. The famous Myers-Briggs Personality Test is partially predicated on Jung’s ideas. This personality test is used by corporations to improve team dynamics and help colleagues understand each other.

Edward Edinger’s book Ego and Archetype works with Jung’s ideas and particularly investigates the religious function of the psyche. I’ll briefly explain this here, but if you would rather pass on the intricacies of this, feel free to skip to the next paragraph. The Psyche is made up of the conscious and the unconscious, and the Self is the centre of the Psyche. The Ego is the centre of the conscious. The Self communicates with the Ego and specifically instructs it towards the process of Individuation, that is, manifesting more elements of repressed consciousness. The Ego becomes aware of its relationship of subordination with the Self, and overtime sees the image of a deity in the Self. This deity image is then projected externally into the real world.

In short, our brains are wired to deify something. As Muslims, we are blessed to recognise the One and Only Deity worthy of worship, Allah, exalted be He. For those who do not deify Allah, they will seek to deify something else. Even atheists will deify something; consider the fervour with which atheists speak of science, or how modern society obsesses over appearance. Jung made a poignant observation of how socialist dictatorial states usurped the role of religion; the state becomes God and policies become creed.

Perhaps this instinct is part of the fitrah, our nature, which compels us to worship. In any case, as humans we have, therefore, a spiritual need. Edinger argues that collective religion (i.e. religious institutes) can fulfil this role by providing a connection to a common deity. Thus, religious institutes have the potential to fulfil our innate spiritual needs.

What happens when religious institutes fail to provide this connection? Edinger discusses four consequences.

The first is unconscious religion; the innate spiritual need that we have is projected onto a secular movement. The zealousness of many contemporary movements come to mind. Lawrence Alschuler, a psychologist, argues that many terrorist groups serve secular agendas by being strongly influenced by politics. More specifically, it is possible to explain why a tiny minority of young Muslims have joined extremist groups through this framework; extremists are known to prey upon those who are disenfranchised with their local mosques, and how they see their parents practising Islam. Thus extremism can be seen as a consequence of an unfulfilled spiritual need.

The second consequence is inflation, in which an individual overvalues their own intellect, and regards their views as the truth. The many inflated egos within the New Atheist movement could be an example. Similarly, the simplistic and crude opinions found within segments of Muslim communities could be a manifestation of this. Nuance and ambiguity are ignored by a forceful ego which regards itself as capable enough to entirely understand reality.

The third consequence is alienation, precisely the kind of alienation which creates the misery and melancholy that characterises modern societies. This alienation could push somebody out of Islam or push them towards despondency.

The fourth is a positive outcome; the loss of a spiritual value enables an individual to confront life’s deepest questions and moves them towards wholeness. Once these questions have been confronted, an individual can move forward towards strong conviction. Perhaps this is a cause behind intra-religious conversion.

Thus, the stakes are high if our religious institutes fail. A plethora of problems arises in the absence of strong institutes. Optimistically, more and more Islamic institutes are appearing; whether that be the Cambridge Eco Mosque, the multitude of savvy centres of knowledge, or burgeoning creative enterprises – British Muslim communities are slowly maturing.

I should end by saying that there is nothing particularly surprising or ground-breaking in saying that a number of problems emerge from inadequate religious institutions. The framework of analysis, however, is valuable and shows the benefits of adopting innovative thought-processes when thinking about our problems.