One such example is the legitimisation of racism among Asian and Arab Muslims; concepts such as facial noor and more overt expressions of racism lead to darker-skinned ethnicities being excluded from certain mosques and hence communities. This inhibits the formation of an Islamic fraternity that crosses ethnic divides.

One such example is the legitimisation of racism among Asian and Arab Muslims; concepts such as facial noor and more overt expressions of racism lead to darker-skinned ethnicities being excluded from certain mosques and hence communities. This inhibits the formation of an Islamic fraternity that crosses ethnic divides.

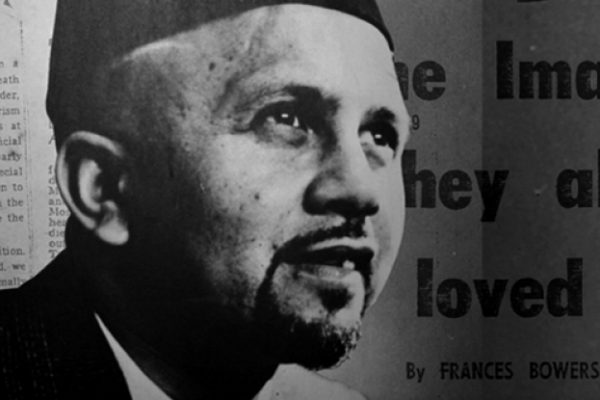

When droves of Muslims flock to the local ‘Pakistani’, ‘Somali’ or ‘Arab’ mosques, Dr Mamnun Khan argues that such behaviour are examples of what he terms ‘ethnocentric’ religion. Ethnocentric religion is the practice of religion that is predicated upon ethnic allegiances. Dr. Khan argues in his new book Being British Muslims that ethnocentric religion has prevented British Muslims from contributing to and advancing British society through a genuine commitment to Allah, which is in stark contrast to the heroic and substantive contributions of the Muslims of yesteryears to their respective societies. The solution to this conundrum is to embrace a theocentric religion. This is the kernel of Dr. Khan’s argument.

The aforementioned examples of clothing and ethnically defined mosques are more benign examples of ethnocentric religion. Dr. Khan highlights serious issues in the British Muslim community that he argues emerge from an ethnocentric commitment to Islam.

One such example is the legitimisation of racism among Asian and Arab Muslims; concepts such as facial noor and more overt expressions of racism lead to darker-skinned ethnicities being excluded from certain mosques and hence communities. This inhibits the formation of an Islamic fraternity that crosses ethnic divides. Other, more egregious examples of ethnocentric religion are the justification of forced marriage, honour-based retribution, FGM, and violent exorcism. The overarching point that Dr. Khan makes is that such practices, varying from softer manifestations such as clothing to serious and ugly crimes emerge from a commitment to Islam that is based on ethnicity, rather than on godliness.

This line of reasoning would resonate with many and is in many respects an important and much-needed critique of the status quo. An attitude of rebellion towards ‘cultural Islam’ exists among many second and third generation British Muslims. But perhaps the matter isn’t as straightforward as regarding ethnic religion as contradictory, or at least different to theocentric religion – although, in some cases it clearly is, such as racism, honour killings, FGM etc.

One may ask what the essential difference is between ethnocentric and theocentric Islam. How can an ethnic commitment be distinguished against a theocentric commitment? This is an especially important question to ask for religious behaviour that seems ethnocentric; for example, both the shalwar kameez and the lack of female spaces in mosques have been justified in Islamic terms by some scholars, even if the latter might offend contemporary sensibilities. For many, then, abiding by such practices becomes genuine religious practice, at least consciously. If one’s intention is pure in an action, then what exactly is ethnocentric about such an action, and is such practice still problematic?

Even in the presence of good intention, if overtly ethnic religious practice are problematic, then what is the alternative? What should Islamic practice look like in Britain? If it should look more ‘indigenous’ i.e. manifested in a way that is seen as less strange in British society whilst remaining within Shari’ boundaries, then what can be said of the Islamically problematic elements of British culture? The point here is that wherever and however Islam manifests, Muslims will always be within the yoke of cultural influence, simply by virtue of them being humans; every human has a culture. In this case, does anything exist beyond ethnocentric religion?

Even if the answers to these questions are not immediately apparent, then the task remains for British Muslims to critically reflect on how Islam has manifested in our lives, both individually and institutionally. Irrespective of what our community makes of this discussion, the gravity of it is clear; it relates to our fundamental duties as Muslims, namely, to adhere to Allah’s religion as closely as we can, and to convey Islam as widely and as beautifully as we can.