Black Muslims are often addressed as “contributors” to a history of Islam that did not truly commence until the second half of the 20th century.

Black Muslims are often addressed as “contributors” to a history of Islam that did not truly commence until the second half of the 20th century.

This post is an abridged version of Shaykh Muhammad Nizami’s article, “There Was No Black ‘Contribution’ to Islam.” Here, Nizami calls us to consider how the notion that Black Muslims have made a “contribution” to Islam, in fact, positions them as “fringe associates rather than inherent fellows.” He demonstrates that the global history of Islam is a story that cannot exist independently of the various Black sahaba, ‘ulama, warriors and saints who make up its very existence. Historical representation often reflects current political representation in our own communities. Defending the rightful place of Black Muslims in Islamic history is, therefore, more than an academic issue of accuracy — it is also a matter of social justice. Nizami thus provides a fascinating account of Ibn al-Jawzi’s “Illuminating the Darkness on the Virtues of the Sudanese and the Abyssinians,” a 12th-century treatise that performs precisely this task.

It’s bold to claim there is no such thing as a Black ‘contribution’ to Islam, and perhaps intentionally provocative, but for good reasons that I’ll point out later. Rest assured, this article certainly doesn’t mean to negate a shared Muslim story, but actually to confront the implicit way Black Muslims are often regarded as fringe associates rather than inherent fellows. To put it as a metaphor, rather than participating as co-chefs it is insinuated that they simply presented some ingredients. One way this is exhibited is by the superficial Bilalicrecital that is a common feature in non-Black Muslim justifications that Islam categorically rejects racism as if the religion itself is the contention. Condescendingly, the prejudiced remind everyone that there is solid proof that Black people have a place in Islam, and ‘he’ is Bilal ibn Rabah, effectively a one-man show. But rarely do we hear about the Prophet’s wet nurse, Umm Ayman, with whom he’d affectionately joke, debate and spend time, or Mihja’, the first believer martyred at the Battle of Badr, or Salim, the most Qur’anically well-informed apostle in early Makkah who would lead the likes of Abu Bakr and Umar in prayer, or Usama ibn Zaid, a favorite of the Prophet (hubb rasulillah) and his military general, or Julaibib, the martyr who killed seven pagans in the moments of his own demise with the Prophet declaring: “I am from him and he is from me,” or both Barirah, a close friend of A’ishah, and the comically lovesick Mugheeth repulsed by her. Bilal et al were not contributions from some nebulous Black “group” in Prophetic history but distinct and equal participants of the shared Muslim story; they made the story what it is.

The popular vernacular and mode of reference towards Black Muslims of the past imagines them as a peripheral entity, and when they are spoken of, it is usually for rhetorical purposes that neglect a meaningful engagement with how they served to shape Muslim history, instead merely pointing out their existence. It’s not lost on the many who see it for what it is: parading the “token black guy” to fend off accusations of racial prejudice. Unfortunately, many Muslims tend to have a racialized view of faith, assuming their particular ethnic group to be vanguards of the “true” Islam. Where the cultural products of some ethnicities are upheld or their cultural dominance in religious settings (even tacitly) maintained as the status quo, the diverse Black experience is either disregarded or looked upon with disdain. “Blackness” is often unwelcome.

The lazy assumption that those of the darker hue (the superficial marker that tends to lead to prejudice) have not made up a significant collective of believers or a distinct Islamic community supports the inaccurate idea that [Black] people cannot be intrinsic to the Islam we practice today.

Ironically, many of those who assume some sense of supremacy in their cultural religious understandings are not only oblivious that Africa had monotheism long before their part of the world, but that Black scholars from the African subcontinent and Arabia have had a profound impact on general Islamic scholarship, not to mention fearless resistance against oppressors. In the history of the Abrahamic religious tradition, Joseph entered into Egypt, the Hebrews settled there developing their traditions until the age of Moses. After the destruction of Solomon’s temple in Jerusalem, it is reported that some of the Children of Israel fled to Africa. Many exegetes citing Ali ibn Abi Talib suggest that a prophet and his followers known in the Qur’an as As’hab al Ukhdud were Africans. After the Messiah, the main bulk of the Unitarians who rightly caused the earliest controversies of Christendom were Africans. And when the Prophet Muhammad’s own pagan Arab people turned on him, he did not turn to Indians, Chinese, Persians, Romans or the rest of Arabia, but a just, Black, African king whom he knew would give sanctuary to the believers. Africa was a second home to the early Makkan converts, a beacon of decency and peace when much of the world was drowning in tyrannical paganism.

The lazy assumption that those of the darker hue (the superficial marker that tends to lead to prejudice) have not made up a significant collective of believers or a distinct Islamic community supports the inaccurate idea that such people cannot be intrinsic to the Islam we practice today. But, can there be an Islam or a Qur’an without Moses, the dark complexioned curly haired prophet, whose story has illuminated the righteous ever since he walked the earth? Sticking to the theme of Qur’anic content, what of Luqman whom some theologians also held to be a prophet, and with most affirming him to be Nubian? God relates this noble character’s lengthy and enlightening advice to his son as a model that every father, for the rest of time, might emulate (31:12-19). In fact, can a mus’haf (scripture) be legitimately considered the Qur’an without parts that mention these people? And in order to emphasize my opening point to this article, were they “contributions” to God’s message or are they actually part of the message itself?

The lazy assumption that those of the darker hue (the superficial marker that tends to lead to prejudice) have not made up a significant collective of believers or a distinct Islamic community supports the inaccurate idea that such people cannot be intrinsic to the Islam we practice today. But, can there be an Islam or a Qur’an without Moses, the dark complexioned curly haired prophet, whose story has illuminated the righteous ever since he walked the earth? Sticking to the theme of Qur’anic content, what of Luqman whom some theologians also held to be a prophet, and with most affirming him to be Nubian? God relates this noble character’s lengthy and enlightening advice to his son as a model that every father, for the rest of time, might emulate (31:12-19). In fact, can a mus’haf (scripture) be legitimately considered the Qur’an without parts that mention these people? And in order to emphasize my opening point to this article, were they “contributions” to God’s message or are they actually part of the message itself?

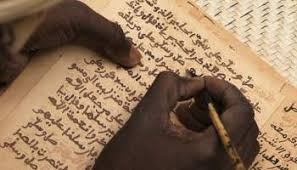

We look back longingly to the “enlightened” Islam of Andalusia, but few consider that the earliest significant foray into Europe was headed by Tariq ibn Ziyad who landed on [the Rock of Gibraltar], from Jabal Tariq (Tariq’s mountain). One of the most significant writers in Islamic history, al-Jahiz, was Black and authored over 200 works on various subjects. Speaking of racist attitudes, he [wrote] an impassioned defence on the qualities and accomplishments of Black sub-Saharan and East African believers. Famed Hanafi scholars such as the muhaddith Jamal-din al-Zayla’i, author of the indispensable hadith work “Nasb al-Raayah,” and the jurist Fakhr al-Zayla’i, commentator of the Hanafi work “Kanz al-Daqa’iq,” both hailed from what would today be Somalia.

… it cannot logically be claimed that addressing the cause of disunity will instigate disunity, unless one is oblivious to the discord the cause is essentially triggering.

… do I seek to be a “defender” [of Black visibility] here? Yes indeed, and I believe so too should all committed believers regardless [of] their own skin tone or ethnic background. There is historical precedence found in the righteous scholars of old; the just caliph Umar bin Abdul Aziz was wholly cognizant of his responsibility to serve everyone, saying to his wife when questioned on his melancholy at night, “I thought about it and I found that I had been charged with the affairs of this ummah, it’s black and it’s red (people)…” Similarly, in facing down the pervasive negative racist sentiments in his time, the erudite Hanbali Baghdadi scholar Ibn al-Jawzi authored Illuminating the Darkness on the Virtues of the Sudanese and the Abyssinians, which sought to address not only the value of their cultural heritage, but also denounce general discrimination against Black people that was rooted in their skin tone. Beginning with an account of Black people as Hamitic and repudiating the biblical notion that Ham, son of Noah, was cursed by his father with dark-colored skin, he continued on to discuss the characteristics of the Sudanese Black folk, describing them with strong bodies and hearts that “cultivate courage” and the Abyssinians with “widespread generosity, upright morality, harmless towards others, smiles, good words, a lucid vernacular, and nice speech.”

Arguing that the controversial nature of the topic will lead to communal rupture is intellectual delinquency at its finest. First, this point is only made by non-Blacks, who as [philosopher John Stuart] Mill put it, overlook the interests of the excluded and see it with very different eyes from those [who are directly affected]. Equally, those who put it that the current political climate means that Muslims should avoid such contentious issues overlook the idea that Muslims differ in what they believe to be a priority to the preservation of the faith or those things that significantly contribute to the everyday ill-being of believers. Second, it cannot logically be claimed that addressing the cause of disunity will instigate disunity unless one is oblivious to the discord the cause is essentially triggering. Such lobbyists might be better served to actually engage Black opinion on a wide level and actually interact with conversations taking place among Black Muslims.

By removing obstacles of an unethical nature and working on a truly shared Muslim identity, one that organically melds the best of what we all are, we should actually anticipate an enriching experience. And while it might require that we all slightly adapt to locate our commonality, rather than becoming nervous, we ought to look at it as part of the maturation process that develops the believing community in exciting and positive ways.

Shaikh Muhammad Nizami is an Islamic scholar currently focusing on applied theology, Islamic law and ethics (fiqh) in a British context, and applied (Islamic) legal theory and philosophy (usul al-fiqh). At a grassroots level, he advocates a return to a God-centered approach to religion and western life, with a deep focus on Quranic narratives and how they inform us how to live meaningfully, specifically as western Muslims.

Shaikh Muhammad Nizami is an Islamic scholar currently focusing on applied theology, Islamic law and ethics (fiqh) in a British context, and applied (Islamic) legal theory and philosophy (usul al-fiqh). At a grassroots level, he advocates a return to a God-centered approach to religion and western life, with a deep focus on Quranic narratives and how they inform us how to live meaningfully, specifically as western Muslims.

(Source)