Despite several hundred years of French imperialism in North Africa, the atmosphere in France regarding the situation of Muslim women still echoes the unsuccessful struggle of the French colonisers to inflict Frenchness on Algerian women.

How Has French Colonisation in North Africa Influenced the Ban on the Muslim Veil?

Despite several hundred years of French imperialism in North Africa, the atmosphere in France regarding the situation of Muslim women still echoes the unsuccessful struggle of the French colonisers to inflict Frenchness on Algerian women.

France’s obsession with Hijab is not new. It finds its roots back in the time of the French colonisation of North Africa during the nineteenth and eighteenth centuries.

The French State’s current oppression of Muslim women echoes the attacks on Muslim women under the colonial regime.

French colonisation: the roots of Muslim women’s oppression in France

Around 1920, the French empire stretched across five continents, including Africa. France invaded North Africa in the 1830s. Ten decades later, it occupied Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia.

The French came with one specific mission, to “civilise” its colonies by absorbing them administratively and culturally. Its ambition was to lift up North Africa to the French standards by bringing Christianity and French culture.

Between the 18th and 19th centuries, French colonisation was based on one of the most known French colony policies, namely assimilation. The word “assimilation” derives from the French word “assimiler“, meaning “to resemble.”

The French policy of assimilation aimed to impose the French system, culture, and way of life on its colonies. However, this policy was not as successful as the British system of indirect rule.

Indeed, unlike the French, the British used the ruler of the people, native police, prisons, and other institutions. Deemed the official French colony policy, assimilation aimed to substitute the culture, language, customs, beliefs, religion, and the law system of the people of Africa with that of the French people.

In other words, assimilation was the belief in the superiority of French civilisation over the “inferior” African one. However, the assimilation policy was a failure for many reasons.

For instance, it was difficult for Africans to affiliate themselves with French culture because of the vast differences between the two cultures. It was, in particular, hard in terms of religion. Most Africans were Muslims and practised polygamy, while French Christians practised monogamy.

Moreover, the French colonisers established a system where administrative tyranny was allowed, meaning governors could define certain offenses by decree. Following the worldwide condemnation of assimilation, France abolished it and brought about the association policy.

After World War II, the French Colonial Administration adopted the association policy to respect the cultures of its colonial peoples and allow them to develop independently. This way, African identity, traditions, and religion were recognised and preserved.

Although Africans were no longer divided as citizens and subjects, the association policy still had strong assimilationist biases. Indeed, French officials would implement French ways of doing things regarding administration and law.

Yet, after 1945, Africans were given more rights, such as a free press and trade unions. Political assemblies and parties were established, providing African rulers with more political power. As a result, they increasingly participated in administration under the French Empire between the 1940s and 1950s. At the time, most Africans served in French cabinets based in Paris.

In 1962, when Charles DeGaulle gave African countries the choice to remain in France or become independent, most African politicians chose to stay. But, what happened in British colonies appeared to have changed their minds.

In Ghana, there was a man called Kwame Nkrumah. He was known for being the leader of the Gold Coast’s movement toward independence from Britain.

Ghana was a British colony known as the largest cocoa producer globally. Nkrumah helped organise Pan-African congresses, linking the emergent educated groups of the African colonies with intellectuals such as activists, writers, artists, and well-wishers from the industrial countries.

In 1947, India gained independence which led to a gradual transfer of power in Britain’s other colonies and inspired Nkrumah to call for the liberation of African countries. As Nkrumah put it, “If we get self-government, we’ll transform the Gold Coast into a paradise in 10 years.”

Moreover, he found that the existing nationalist groups were too tied to colonial business interests. He then established a new party called the Convention People’s Party (CPP), which made him the leader of Government Business, an actual prime minister responsible for internal government and policy. His philosophy revolved around one of his famous slogans, “Seek ye first the political kingdom, and all else shall be added unto you.”

Nkrumah became very influential across Africa, and when Ghana gained its independence, it became a model for the rest of the continent. By the mid-1960s, more than 30 countries had become independent.

However, to better understand today’s challenges Muslim women face in France, it is necessary to recall the French’s colonial past in Algeria.

In Macron’s France, the Lessons of the Past Remain Unlearned

Under the French empire, Algeria was the most important colony. When France invaded Algeria, the French were confronted with different religions and cultures, so to impose their views on Algerians, they tried to erase their identities. Algerian women were the main target to attain their ends. The veil played then a significant place during French colonisation.

During France’s occupation of Algeria, Frantz Fanon highlighted the French’s intention to undress Algerian women and “liberate” them from their veils in his book Algeria Unveiled. He explained how France sought to maintain its colonial hold through Algerian women and destroy Algeria’s society.

In a famous quote, he said, “If we want to destroy the structure of Algerian society and its capacity for resistance, we must first conquer women; we must seek them behind the veils where they hide and in the houses where men keep them out of sight.”

For the French army, the unveiling was a strategy to win the hearts of Algerian women crushed by what they called “outdated patriarchy”.

A couple of centuries ago, French settlers in Algeria pressured Algerians to remove the veil. For example, they allowed the heads of Muslim families to vote only if their wives took off their veils.

When Algerian workers were invited to participate in the Christmas meal organised by their boss, they were urged to bring their wives with them. French directors would put out of work all the Algerians whose wives arrived with their heads covered.

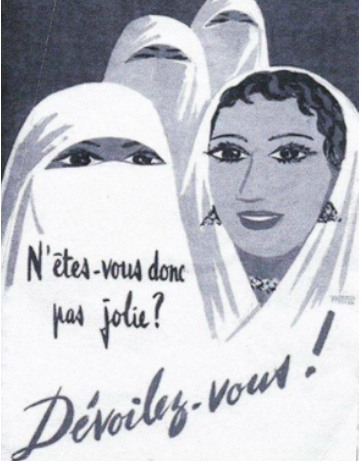

Another troubling aspect of the obsession with Muslim women’s dress was French authorities’ unveiling ceremonies practised in public places.

In 1958, French colonial authorities organised ceremonies in Algeria’s public spaces where Algerian women would take off and burn their veils to demonstrate liberation from the patriarchy.

These ceremonies were illustrated through a famous colonial poster entitled “Aren’t you pretty? Unveil yourself!” by the French Army during the Algerian war of independence. These posters covered the walls of Algiers, inciting women to remove their veil or haik.

Following the colonial era, the veil was long used as a symbol of resistance during protests in Algeria. It emphasises Algerian identity and sends a message to the West to keep out of it.

Although French colonisation in Algeria ended on paper in 1962, France’s colonial past consequences are still felt today in France’s society through forced integration and a war waged against Islam. To this day, Islam is still considered a religion that needs to be quelled and controlled in France.

The weaponisation of French laïcité against French Muslim women

Since its creation in 1871 by anticlerical militants and inspired by French republicanism, French Laïcité stirred controversy.

At the time, Laïcité was used to counter the power of the Catholic Church; now, it is used to define a French identity that excludes Muslims and predominantly Muslim veiled women. French Laïcité aims to drive religion out of the public space. However, regardless of the time, women are still seen as a potential danger to the Republic.

Between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, women were accused of being influenced by priests. Today, Muslim women are being blamed for refusing to assimilate into the French culture. This goes back to colonisation, where French women were considered more civilised than veiled Algerians.

Between 1792 and 1852, Laïcité was merely an idea. It was only by the Third French Republic that it became concrete. In 1905, the Chamber of Deputies passed the 1905 French law on the Separation of the Churches and the State.

French authorities then began to secularise the French society by implementing secular schools and healthcare. It also banned public prayers. The law thus introduced four principles:

- Freedom of conscience

- Religious choice as a private matter

- Separation of State and religion

- Equal respect to all faiths and beliefs

The word Laïcité first appeared in the French Constitution in 1958, specifically in Article 1, “France shall be an indivisible, secular, democratic and social Republic. It shall ensure the equality of all citizens before the law, without distinction of origin, race, or religion. It shall respect all beliefs.” As a result, French authorities do not recognise, fund, or subsidise any religion.

In 2010, France became the first European country to ban full-face veils, namely the Burqa and Niqab, in public places.

Although France is deeply attached to its traditional trinity of liberté, égalité, fraternité, the latter has been increasingly downgraded over time. With the rise of terror attacks in Europe and especially France these past years, Islam has been at the heart of political debates.

Consequently, the controversy around Muslim women’s clothing has amplified in French politics, leading to increased attacks against veiled Muslim women.

According to a 2019 study by the French Institute of Public Opinion (IFOP), 42% of Muslims have experienced religious discrimination at least once in their lives. Testimonies of French Muslim women have recently shown that the French motto—liberté, égalité, fraternité, has long been twisted. In France, there is no longer liberty of religion. Muslim women, especially those who wear Hijab, are excluded from French society.

Today, Muslim women cannot go to school or work in Hijab. They continue being discriminated against daily, yet French President Macron continues to pursue Islamophobia as a national policy.

Albeit French secularism defenders claim that it is applied to all religions, laïcité turned out to be incompatible with Muslims’ practice of Islam, which is not the case with that of Judaism or Christianity. However, the French government has failed to acknowledge such disparity, directly targeting Muslim women.

In the past 20 years, France’s legislators passed many laws on laïcité to undermine Muslim women’s lives in French society, including the 2004 ban on headscarves in school. Macron’s recent bill on separatism aimed to fight against terrorism and political Islamism when it focuses on stripping the average Muslim woman’s rights rather than tackling radicalisation.

Recent Macron’s moves have shown how the French government is determined to wage war against Islam by slowly encouraging freedom from religion instead of promoting the actual purpose of the 1905 law, which is to enforce freedom of religion.

Despite several hundred years of French imperialism in North Africa, the atmosphere in France regarding the situation of Muslim women still echoes the unsuccessful struggle of the French colonisers to inflict Frenchness on Algerian women.

References

A New Civilising Mission: French Colonialism

Secularism and Religious Freedom in France

Conseil Constitutionnel: Anglais

France: Senate Votes on Muslim Veil Ban

Selon un sondage 40 des Musulmans de France ont fait l’objet de racisme