My case has unearthed the sheer level of disconnection between judges and the legal system and the lived experience of Muslims. Until the law is changed in this arena, including enforcement rates, we will continue to witness and experience the emboldening of racial and religious abuse.

No Action in Azeem Rafiq’s Case Shouldn’t Come as a Surprise. It’s the Norm from Courtrooms to Classrooms

My case has unearthed the sheer level of disconnection between judges and the legal system and the lived experience of Muslims. Until the law is changed in this arena, including enforcement rates, we will continue to witness and experience the emboldening of racial and religious abuse.

Last week Sajid Javid tweeted that the ‘P word’ is not banter, which was the attempted explanation for the racial abuse cricketer Azeem Rafiq has experienced. Triggering a political and social media storm, many have called out the cricket board for not disciplining those who subjected Rafiq to this abuse.

It is not the first time I have come across an institution failing to take action over discriminatory behaviour. Based on my interactions with others from diverse backgrounds and my own experiences, lack of action to address discrimination is in fact the norm across workplaces and courtrooms.

The discussion around Rafiq’s experience has brought up sour memories from my own experience that extend back to September 2015. I was dismissed after raising a safeguarding concern that 11-year-old children were shown a graphic, 18-rated video of victims jumping to their deaths during the 9/11 attacks.

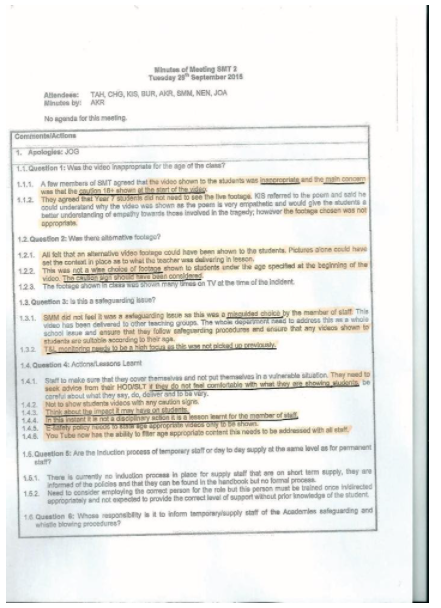

I was told that I must leave the premises immediately, as I was ‘uncomfortable with the curriculum’. I proceeded to seek justice in the employment tribunals for what I believed to be unfair dismissal. During the legal process, documents were revealed which showed that the Senior Management Team (all of whom were white) agreed the video should never have been shown but decided to not discipline the (also white) teacher who showed the video while taking no action to rectify my wrongful dismissal.

After a long and drawn-out process, in 2017, the Employment Tribunals ruled in my favour for unfair dismissal, public interest disclosure, and victimisation. The religious discrimination claim however, was refused, despite clear evidence that the school discriminated against me because I was a Muslim woman.

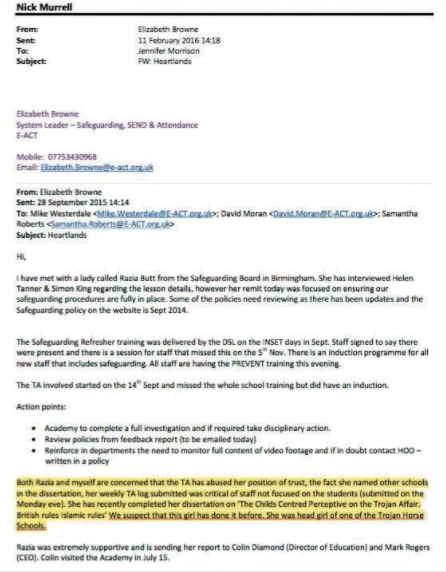

As well as the SMT team meetings, additional evidence included an email in which the senior management team associated me to be involved in the so-called Trojan Horse affair simply because I was a head girl during my secondary education at one of the schools. The courts completely ignored this.

The tribunal’s decision to refuse my religious discrimination was based on the premise that a Jewish or Christian woman would have been treated the same way. In my appeals and reconsideration applications, I fiercely argued that without three key factors, a Jewish or Christian woman would not have been treated as I had been.

Firstly, I argued that there must be first a visible marker of religious identity, as I was a visible Muslim woman by wearing the hijab, second, there must be a Trojan Horse Affair equivalent where right-wing members of the respective communities were alleged to be taking over state schools, and third, a 9/11 equivalent where the perpetrators were aligned with the extreme fringes of the respective communities.

Without these three factors, a comparator of Jewish or Christian faith would not receive similar treatment. The tribunals failed to consider these significant elements of the argument leaving me to experience a court system that is set up to allow both primary, and secondary discrimination.

Furthermore, the representatives for E-ACT, the academy chain responsible for the school argued unreservedly, as part of their defense, that I was against 9/11 being taught on the curriculum. They included within the bundle documents the full 16-page poem by Simon Armitage to advocate this point, as the longer version of the poem did contain a reference to 9-11.

This was despite the fact that during the lesson, only the first page of the poem was being taught as part of the curriculum. Nonetheless, the defense marched ahead with concocting a false story detailing how I was against 9/11 being taught on the curriculum, the very curriculum I learnt as an inner-city Birmingham state-school pupil, and managed to go on to study at Oxford.

It was impossible to argue in court that the defense was Islamophobic, and also a secondary form of discrimination, as their defense was a form of ‘defense’.

In 2018 then, I founded the Equality Act Review to convince Parliament that reviewing the Act will enable a fairer and more equal society. In July 2021 we launched our report “Equality Act 10 Years On”, in which we put forward significant models of reform, and called for new protected characteristics to be added such as hair, accent, weight, socioeconomic background, and the strengthening of current protected characteristics.

For Section 9 on Race, we argued that ‘racialised’ groups such as Muslims and Sikhs ought to be protected since, while Islamophobia and Islamophobic attacks are on the rise, the equality act does not recognise Muslims as a race. In my first preliminary hearing in February 2016, my race discrimination case was struck out due to the Judge’s view that ‘Muslims are not a race.’

Sajid Javid and others in Government therefore cannot only call out the Yorkshire Cricket board. They must acknowledge the wider set of issues that allow those responsible to get away with discrimination. They must also recgonise and address the long genealogy of racism and discrimination, and the avenues and capillaries that allow such forms of abuse to continue in the 21st century.

It is not enough to say the cricket board should have taken action. Workplaces and courts also need to recognise racism and discrimination.

My case has unearthed the sheer level of disconnection between judges and the legal system and the lived experience of Muslims. Until the law is changed in this arena, including enforcement rates, we will continue to witness and experience the emboldening of racial and religious abuse.