“Mental illness is like a physical illness, like cancer, like diabetes, like cholesterol,” says El-Zein. “There are chemical imbalances that need to rebalance. It is unfair to say to someone who is suffering [that they lack faith], because faith might be the only thing keeping them alive.”

“Mental illness is like a physical illness, like cancer, like diabetes, like cholesterol,” says El-Zein. “There are chemical imbalances that need to rebalance. It is unfair to say to someone who is suffering [that they lack faith], because faith might be the only thing keeping them alive.”

“Mental illness is like a physical illness, like cancer, like diabetes, like cholesterol,” says El-Zein. “There are chemical imbalances that need to rebalance. It is unfair to say to someone who is suffering [that they lack faith], because faith might be the only thing keeping them alive.”

She sits at her desk, typing vigorously as the desktop light illuminates her features, revealing striking eyebrows and a delicately pinned floral hijab that perfectly drapes her fair face.

Turning to some handwritten notes from therapy sessions and then shifting her gaze intently back at the monitor, she works diligently through the evening, updating clients’ medical charts to track their progress.

Students go in and out of her cramped office, a box-shaped space with an L shaped desk, low seated bamboo chairs, and a side table overflowing with self-help books. And yet, dimly lit lamps and nature-themed wall hangings give it a homey character, contributing perhaps to the cheerful goodbyes and wide smiles exchanged at her door.

But while she remains well poised and demure on the inside, it is an entirely different story outside.

She plays wildly with the snow, honks boisterously at “silly drivers”, laughs till her belly aches, excitedly watches Anne of Green Gables, and shoots Instagram stories wherever she goes.

Such is the life of Berak Hussain, widely known as “The Muslim Counsellor”, a woman of faith who graces television screens and news articles as a bold advocate of mental health, who has also battled demons in her own personal life.

But even with the curveballs life has thrown her way, she has learned to separate her private and professional life, a conscious decision made to thrive as a successful psychotherapist.

* * *

“I have to reset now,” Hussain says, her voice trailing off as she sits relaxed on her chair at Carleton University’s Counselling Services, black leather peeking out under her chocolate-colored shawl covered in intricate beading.

She has busied herself with her phone, where she scrolls down the many WhatsApp updates she’s received about a family wedding, and oohs and aahs at their vibrant outfits and familiar faces. She has a little time before her next appointment arrives, a new client whom she’s never met.

She decides to use this time to meditate and briskly heads out of her office to the common area sink she shares with other counselors to perform ablution, the Muslim water purification ritual completed before prayers.

Mental health posters are plastered throughout the room, along with a painting of a colorful elephant that seems to be spraying sparkly colors aside a glaring notice of confidentiality. “This is a safe space” reminds the board next to the conference table.

Back at her office, she lays down her prayer mat just barely to the side, and almost as though transcending to another dimension, recites her prayers.

“After each session,” says Hussain, “I have to practice self-care. Whether it’s going on social media, or meditating, or just taking a power nap, it’s very important for me to reset so I can take on the next client.”

The work of a psychotherapist is often grueling, with long work hours and even longer nights where she finds herself up late, thinking about her client’s problems, especially the ones she couldn’t solve. “As much as you want to separate work and life, you’re still human and the struggles people go through affect you,” she says.

Though 61% of therapists experience a high risk of burn out within three years of work, as noted by nationally certified counselor Dr. Kyle Baldwin, Hussain has been practicing at Carleton University in Ottawa, Canada for over ten years now, with no intention of slowing down.

Though Hussain is evidently Muslim, her clients practice a wide variety of faiths and beliefs, but this does not hinder them from finding a connection together, as therapists are trained in various cultural models and sensitivities. However, it is the Muslim students, belonging to a growing group of over 750,000 Canadian Muslims, who specifically seek her out, feeling she can relate with their issues.

“I love what I do,” she says, emphatically. “I don’t feel like it has been ten years because it doesn’t feel like work for me.”

There are the occasional instances that stump her and throw her off her very concerted efforts to leave work at work. “It happens to the best of us,” she says. “Every time I think of a client and their ordeals, I send them prayers and positive vibes, and then I move on. Or at least I try to.”

In her book Simple Self-Care for Therapists, grieving specialist and psychotherapist Ashley Davis Bush stresses that therapists must guard themselves against compassion fatigue, which often happens when one gets hung up on their client’s situation. “Intentional self-care then isn’t just essential,” she writes, “it is a survival tool… for therapists to do their work effectively.”

Though Hussain has managed to compartmentalize successfully for the past ten years, she didn’t always know she would be a therapist, let alone become a devoted lifer—one who has dedicated their professional life to one career.

Born in America and moving from country to country as a child, from England to Libya, then to Algeria and ultimately to Canada, she lived her adolescent years under mounting pressure from her father, a physics professor, to excel in school.

“He meant well,” she says. “But he expected me to be a doctor, and finish my studies quicker than the normal route, but my body just couldn’t take it.”

In class one day, she began to sweat uncontrollably and started experiencing tremors throughout her body. “No one knew what was going on,” she adds. “The ambulance had to come and take me away.”

Carted from doctor to doctor, from neurologists to hemoglobin specialists, it wasn’t until a Muslim cardiologist took one look at her, her father and their tense body language that he was able to diagnose the problem right away.

“Back off, he said to my father,” says Hussain, lightheartedly. “He said to him, ‘You’re putting too much pressure on your daughter. Let her enjoy school’.”

That cardiologist had most likely seen this all too often, where many Muslim parents exert academic pressure on children to strive towards traditional careers such as medicine and engineering, as noted in a UK Social Mobility Commission report produced in September last year.

After realizing her health was more important than a career, Hussain slowed things down and completed high school with classes she actually enjoyed taking. Still aspiring to one day become a doctor, she struggled to keep up with science and math classes.

“It just wasn’t for me. I liked the creativity, the social, the writing, the psychology. But I still kept at it, not understanding my own limitations,” she says.

Then one day, as a job assistant at the University of Ottawa career center, Hussain attended a program on behalf of students interested in counseling careers. “It was here I realized this is exactly what I wanted to be doing,” says Hussain, “—and I remember holding the pamphlets in my hand, and thinking to myself, why am I not doing this?”

Instead of taking back what she had learned to the career center, she hurried to her phone and rang her mother, whom she excitedly told what had transpired. “It was like destiny made me find my path. And I haven’t looked back ever since.”

* * *

“Hi, I’m Berak Hussain. Welcome to my counseling session here at Carleton University. This is a safe space for whatever you want to talk about—,” says Hussain, role playing what happens in her office during sessions.

The introduction is followed by a brief notice of the confidentiality policy, an explanation of the short-term therapy procedure as opposed to long-term therapy due to a lack of resources for over 35,000 students, and the shared-care model: “We share the notes we take with nurses and doctors here, and they remain confidential. The only time we may need to break this is if we are subpoenaed by the courts, which is rare, or if there is a high risk of suicidality for purposes of protection, or if there is abuse involving a minor, again for protection.”

For now, she sits next to the door during sessions, in case a client has a violent outburst and she needs quick access to exit. Her updated chair will be coming in soon, the one with a hand-held button on the side that can call for help if needed.

“Nothing has happened in the ten years I’ve been doing this, but it’s always good being prepared,” she says.

Hussain collects boxes from her temporary office and tethers a beveled mirror on top of a large blue container where she’s piled her lamps, memorabilia and the black and white nature wall art she pairs with green leatherleaf ferns. She lugs these to her car, which she drops off at her new office space across campus, a larger room with many windows and brighter lights.

She wraps up her notes, shuts off the monitor and closes the door behind her. And while the day has ended here, a myriad of projects awaits her at home.

* * *

Berak Hussain’s clients at Carleton University are largely comprised of the student body, but most of her free time is spent outside of work advocating for mental health, especially when it comes to her Muslim community.

“There is such a need for mental health work in the global Muslim community; I’m constantly getting calls and emails from people suffering from mental health issues all around the world —US, UK, Canada, Australia, France, Lebanon, Iraq, India, Pakistan, Iran, Mauritius, Denmark, Nigeria, etc— asking for me to help them cope with their issues” says Hussain.

Once, after Hussain had finished speaking at a conference about mental health, a man in the long line waiting to meet her approached her and broke down. “Please be my wife’s counselor,” he said, desperate.

This is why she intends to open a private practice in the future, where she can accommodate the Muslim community’s problems full-time and still be able to make a living. “Maybe there’s a generous patron who would want to offer this service for the community,” she says, “especially if I do therapy remotely, because many Muslims cannot afford therapy. This is definitely a need we have to address.”

Maya Baalbaki, a social work advocate and member of Al Huda Center in Scarborough, Ontario, agrees: “Our communities need to be able to freely discuss their issues, to come into the center and feel safe and know they always have someone they can speak to.” She recently facilitated a mental health event in which Hussain was flown down as its guest speaker.

Baalbaki initially faced pushback from community leaders who were unconvinced that mental health issues existed in the community.

But after over a year, her persistence paid off.

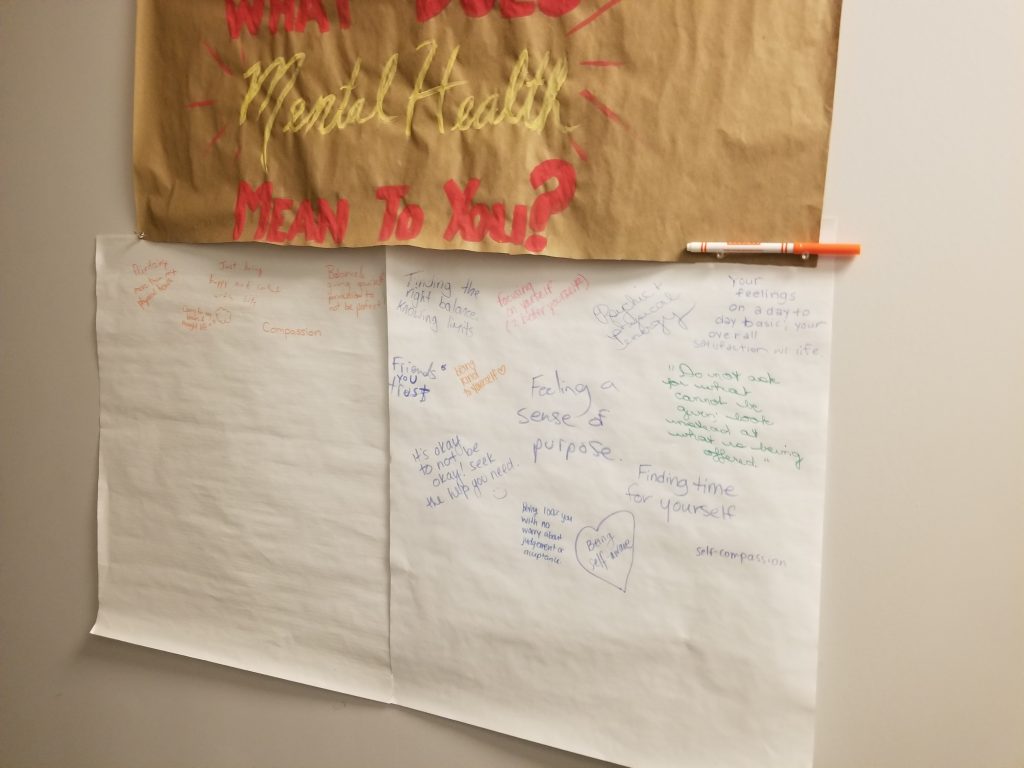

“All the issues came to surface… and Berak was absolutely amazing,” says Baalbaki, delighted. “She connected with both the youth and the adults, especially when there is such a stigma associated with mental health. She managed to get them to open up by doing activities and having discussions with them to get them to feel safe. I have never seen a speaker be able to do that, whether it’s a scholar or a professional, and there was a lot of good feedback. Everybody loved her.”

As Hussain was interacting with her audience, Baalbaki observed her dialogue and body language, and it wasn’t difficult to see why her clients at Carleton sought her out. “No one was bored, even for a second,” says Baalbaki. “To hear adults speaking up about their issues, and that even to someone who is not from their center and is speaking to them for the first time, that is incredible.”

After years of doing this, Hussain says the secret to connecting with people is using the right language. Though speaking Arabic helps, it is the terminology used that goes a long way.

“When I speak to older people, I ask, you can’t sleep, your mind is constantly racing…. What is that?” says Hussain. “If I told them the word ‘anxiety’, they would be put off because they know it relates to mental illness. I describe it to them, and they connect with that.”

Many in the Muslim community also experience depression, especially in the post 9/11 era that has brought on Islamophobia, according to a report by the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding. However, Hussain doesn’t approach the issue headfirst. Instead, she asks the audience if they have noticed any changes, if they’re feeling lethargic, sick, not wanting to go to work or visit friends and family. “I’m not talking about the ups and downs we all go through,” Hussain clarifies. “It’s the long period of time someone is experiencing this, and they need to connect with the concept, not be put off by the word ‘depression’.”

Over time, Hussain has come to realize many individuals have negative thoughts at least once in their lifetime. But the clients who come to see her do not have fleeting thoughts, “They are really depressed for long periods of time,” she says. “I want to move them away from self-harm and see what we can do to make them look forward to in life.”

It has taken time for the Muslim community to focus on mental health, but through her travels around the world, she is seeing progress.

“For the older generation, there is a hesitation because they were raised to believe that one should never talk about private problems. That stays at home,” she explains, gesturing lightly with her finger. “And when someone talks about it publicly, they are believed as weak in faith, so there’s this wall of toughness.”

Hussain experiences positive change when she has face to face encounters with people who are willingly engaging, and the shells slowly begin to break.

This ‘aha’ moment, said to be a therapist’s golden dream, is what Hussain has dedicated her entire life to; the breaking of superficial shells, to finally empower the core.

* * *

Rasha El-Zein first came across Berak Hussain and her work as The Muslim Counselor when they both were featured in a UK based documentary “The Cloud of Depression,” which aired on May 24 this year, observing World Mental Health Day.

Except, their stories were very different.

Unlike Hussain, El-Zein is not a therapist, but rather a young Muslim woman who has battled severe depression most her of her youth and is unafraid to speak about it in the community.

“People have come up to me, since I decided to go public about all this, saying Rasha, don’t speak about it openly, people will think you are weak, that you are vulnerable,” she says. “And others will come up and say, ‘You’re so brave for doing this,’ and that’s the bizarre part, because essentially they’re saying it’s a brave thing to speak about a sickness, which shows how much stigma there really is.”

El-Zein’s thoughts are not farfetched. In the Journal of Muslim Mental Health titled “Mental Health Stigma in the Muslim Community” writers Ayse Ciftci, Nev Jones, and Patrick Corrigan highlight that cultural attitudes and stereotypes against mental health foster the stigma, and that it is harmful effects such as being “publicly labeled” or “facing injustices by the community” that turn sufferers away from seeking professional help.

“It’s a tough condition,” says El-Zein, feebly. “It’s a stigma that you are weak, you lack in faith, you bring shame, that you are possessed. Every culture has a different interpretation of it, but they don’t get that mental illness manifests in physical forms and people can’t understand if they haven’t been through it.”

Taking one look at her though, with her heart-shaped face and deep brown eyes that crinkle as she smiles, it is difficult to tell the ordeals she has faced. Her life with depression began four years ago, but she believes she’s been battling the illness since the age of 14.

“My first episode was at university and lasted for three months. But my second episode lasted for a year, which I believe cemented my diagnosis,” says El-Zein.

Mounting family issues and becoming tangled in a toxic relationship with a man whom she had fallen in love with would trigger the longest and most painful episode of her life. In this time, she would cry every day, and find herself unable to socialize, talk to friends and family, or even perform everyday tasks such as brushing teeth, washing herself, and eating. Her mother had to get her out of bed, and she ended up leaving work because she physically felt ill from the emotional toll her mental health was having on her body. “All my energy would be going to crying, sleeping, or being zoned out watching TV,” she says, almost in a whisper. “It was a constant sinking feeling. I didn’t want to be alive. I didn’t want to kill myself, I just wanted to stop existing, because being alive felt like a burden.”

Stuck in an endless black hole of pain and suffering, it wasn’t faith that pulled her out, but a small white bitter tasting pill called Citalopram that emerged as her knight in shining armor.

“This is a conversation we need to have, because medication also carries a lot of stigma,” says El-Zein. “I’m not saying that we should rely on medication, and of course we should be aware of the side effects and dangers of addiction. But milder ones can help balance hormones and lift you out of your situation while you figure out other ways to cope.”

Though religion has always been dear to her heart, faith wasn’t particularly helpful in this situation as it was driving her to further despair. “I felt as though I was holding on to my faith by a piece of string,” she says. “I constantly felt like I was being ungrateful to God’s blessings, because I felt like nothing was good enough, that I wasn’t worthy of love, and it drove me to think of my life as a burden that I couldn’t bear anymore.”

Due to this, she admonishes people who entertain the idea that victims of mental illness lack faith, when it has little to do with it. “Mental illness is like a physical illness, like cancer, like diabetes, like cholesterol,” says El-Zein. “There are chemical imbalances that need to rebalance. It is unfair to say this to someone who is suffering, because faith might be the only thing keeping them alive.”

* * *

Berak Hussain’s home is reflective of the tone she sets in her sessions; relaxed, casual, unfiltered, feeling. A modest home stacked three stories high, her blue and yellow colored kitchen sits next to a family room where her daughter’s Legos are sprawled everywhere, line lights hang low around the ceilings, and a Majlis is spread with soft eccentric carpets and large floor pillows.

“Hello baby,” she says, cooing. “You like that that don’t you,”

She gives Lozze, her charcoal gray cat, a long belly rub, which he happily accepts with all four paws curled up, purring incessantly.

“Mental Health is Islam,” says Hussain, settled into a futon, with Lozze at her feet. “And Islam is mental health.”

She is referring to the opinion that mental health is an overarching umbrella that is responsible for all our faculties that give us the right balance to stay happy and healthy.

Sheikh Ali Shobeite, an imam of the Muslim Community Center of Montreal, agrees.

“[Islam] emphasizes compassion, support, and refrainment from judgment and guilt association,” he says. “Just as if you would suffer from diabetes, you go to the doctor for diagnosis and treatment, because religious advice may be insufficient, ineffective or inaccurate to diagnose such biological diseases.”

He has known Hussain since she was 16 years old and has seen the personal challenges she overcame in her life and community. “Berak is trying to address this important and overdue issue of mental health with current knowledge,” says Shobeite. “She needs support… from local community leaders and scholars to help her work with the community in a synergistic manner.”

Hussain, who has worked with various religious leaders all over the world such as Sheikh Nuru Mohammed, Sheikh Mohammed Al Hilli, and Sheikh Asad Jafri, recognizes that Islam works in tandem with mental health, because it focuses on the physical, the mental, and the spiritual. “A lot of our practices, on meditation, on nurturing good relations with people, on living a genuine life, on healthy eating, on frequent exercise, all relate to having good mental health,” says Hussain.

To her dismay, however, many of her clients’ families and environments are not embodying true Islamic values and are contributing to the rise of mental illnesses within the community through trauma.

In one of the most horrific cases that have come her way in her ten years of practice, Hussain recalls the case of a young girl who went through such excruciating experiences inflicted upon by her own family members who were affluent aristocrats of a large Muslim community.

In another case, an international student was caught in a political crossfire in a so-called Islamic country and being sent back home was a death warrant signed. Hussain and her team worked exhaustively to ensure the student was not sent back, as his entire family had already been killed. Eventually, he was granted asylum to continue living in Canada, a bitter-sweet moment filled with relief and sadness.

“In my job as a therapist, I have never and will never impose religion to clients,” says Hussain. “At the end of the day, we all have the same basic necessities. There is a universal aspect to therapy, and true faith is all about being more human.”

* * *

It’s a Saturday, which means sleeping in is allowed.

But lazing around is definitely not.

Chirpy and bright-eyed, Hussain is excited to tackle the day. The itinerary includes waiting in long lines to snag a cheese pie from Alladins, drinking that mandatory cup of decaf Irish cream coffee at Café Nero, and ending the day with a finger-licking supper at AsSayyed Resto.

And at all these places Hussain visits, be it the lunch eatery at Carleton University, the numerous stores on Bank Street, or the mom and pop run cafés and restaurants, owners come out to meet Hussain and lovingly chat her up, giving her discounts and even freebies.

Today, as she leaves AsSayyed Resto, she is surprised the chef hasn’t come to greet her yet, when their eyes meet at the entrance and he stops dead in his tracks. They converse in Arabic, where he relentlessly apologizes for not having realized that she had dined here, and frets over the waiter who had failed to let him know. “May God forgive you,” he says to him grumpily, which Hussain finds quite humorous.

“Everyone wants to be happy, be at peace, be respected, have serenity,” says Hussain as she heads towards her car, her high heeled—wedges, she corrects— boots slushing on the frosty cold ground. “The key to attaining this is to never give up, to never lose hope, because there is a permanent solution for every temporary problem.”

Tonight is a night for self-care; tomorrow she will be speaking at a conference in her local community, and on Monday she will have back-to-back sessions with students at Carleton.

And though Hussain has successfully separated her private and professional life, she is still one and the same person.

Genuine, attentive, and most importantly, free of judgment.

Works cited:

https://globalnews.ca/news/4349809/mental-health-muslim-canadians/

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/288623548_Mental_health_stigma_in_the_Muslim_community

https://www.sicknotweak.com/2016/08/mental-health-north-american-muslim-community/

http://mentalhealth4muslims.com/talking-about-mental-health-in-a-muslim-community/

https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4349&context=etd

https://themuslimvibe.com/faith-islam/in-practice/muslims-and-mental-health-issues

http://psycnet.apa.org/record/2014-34868-004

https://icnareliefcanada.ca/family-counselling

http://books.wwnorton.com/books/Simple-Self-Care-for-Therapists/

https://www.humanityinaction.org/files/743-ActionPlan-HasherNisar.pdf

https://www.lkmco.org/job-want-job-think-understanding-young-muslims-aspirations/