If we open our history books, the first to display and use of this behaviour were colonial officers.

If we open our history books, the first to display and use of this behaviour were colonial officers.

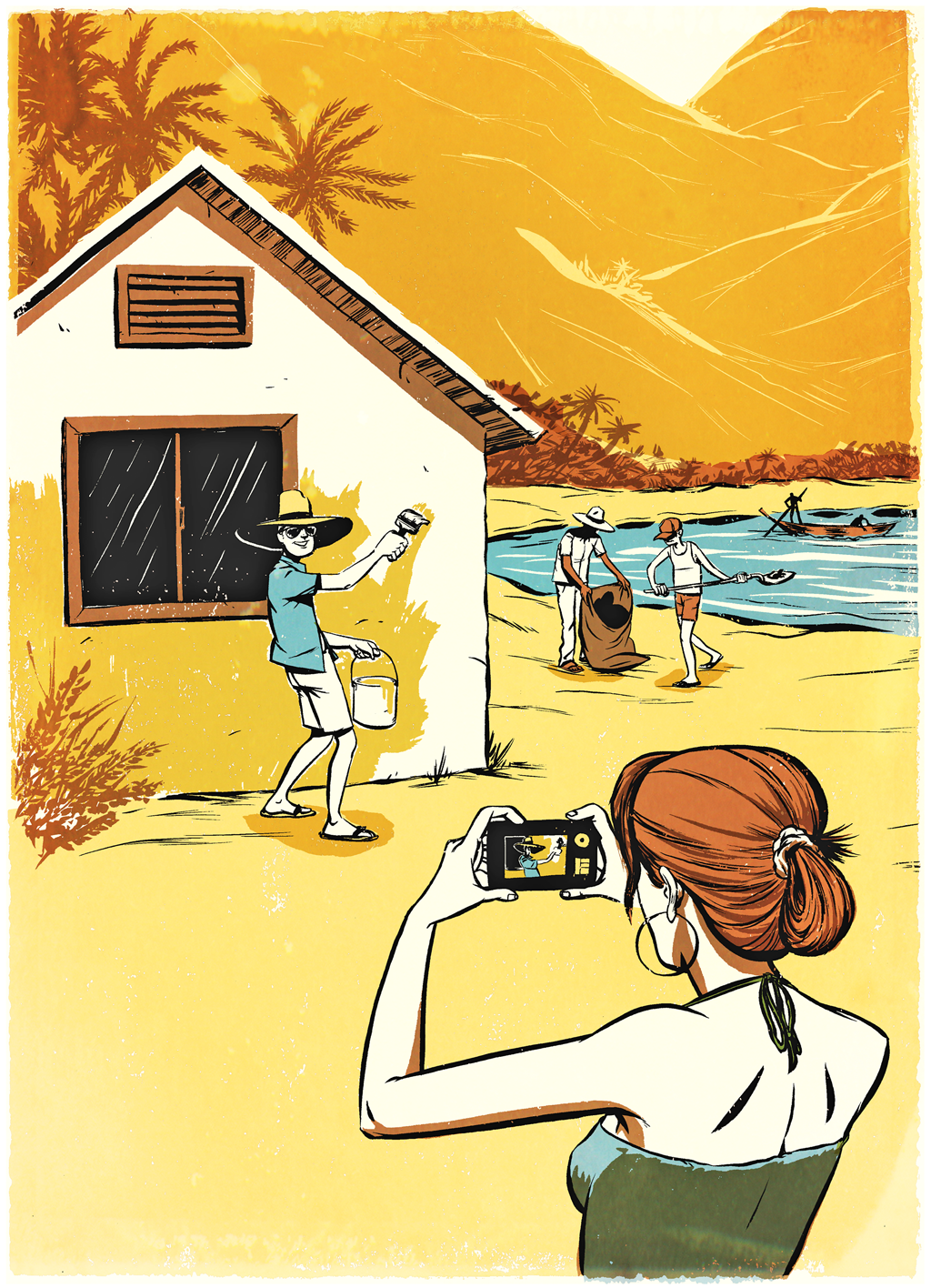

Recently, a Norwegian charity group (SAIH) launched a guide aiming at tackling the problem of ‘voluntourism’: people travelling the world with a charity for a work assignment which in reality ends up being more of a holiday abroad. While this guide is aimed at predominantly white organisations, the Muslim charity sector is not safe from this trend. Far from just pointing out problematic behaviours for the sake of criticism, SAIH’s guide offers tips and suggestions for improving charities’ social media practices.

Voluntourists tend to use poverty at their advantage, feeding their social media with highly problematic content: selfies of themselves surrounded with unaccredited children or sensationalist pictures propagating stereotypes (such as seeing Africa only as a continent plagued by war, diseases or poverty), without asking people’s names or even their authorisation. It is also called ‘poverty porn’. This behaviour dehumanises people as they are stripped of their names, story and background, only being used as the personification of suffering. Thus, it is even more paradoxical for Muslims to do it to our own brothers and sisters in religion.

The guide, picked up by AJ+ in December, tries to address what is commonly known as the ‘White Saviour Complex’. This trend originated from the phenomenon of ultra-privileged volunteers working with large multinational charities (85% of US charity volunteers working abroad are white), feeding the narrative of ‘saving’ the seemingly deprived areas from war, famine and more. In reality, only a little amount of very specific positions (mostly medical) are needed abroad. As a consequence, unqualified volunteers are not contributing to any betterment of the local areas; it does more harm than anything else. Unfortunately for areas in need, the most tangible outcome of this practice is perhaps that extra line volunteers get on their CV for future career perspectives – even JK Rowling got vocal about this.

The #voluntourism charity tells volunteers that they will be able to 'play and interact' with children 'in desperate need of affection.'

— J.K. Rowling (@jk_rowling) August 21, 2016

This, in short, is why I will never retweet appeals that treat poor children as opportunities to enhance Westerners' CVs. #Voluntourism

— J.K. Rowling (@jk_rowling) August 21, 2016

However, if we open our history books, this phenomenon is nothing really new; the first to display and use of this behaviour were colonial officers (see below). They too, believed that ‘they were here to help’, while treating people from colonised societies as prizes and trophies. The colonisers justified they were invading countries for a good cause: to ‘civilise’ and ‘educate’ the ‘ignorant’ ‘savages’. Therefore, there was a certain pride in showing people stripped of their traditions, culture and spirituality to conform to Western norms. It seems therefore paradoxical that Muslims, as an oppressed community in the West, end up dehumanizing our own brothers and sisters with the same tools than the oppressor, replicating its very same racial stereotypes and systems of domination. Unaccredited African children, Syrian orphans and other refugees regularly feature in social media feeds for either promoting charities’ works or some people’s ego.

It is fair to acknowledge that big charities want to adopt practices that work best for promoting their works and collecting donations, and it is fair to acknowledge that increasing responsibilities make them work under high pressure, and that leads to compromises. However, there is a problem when these practices, uncritically copied from modern corporate culture, do not fit any ethics of respect for human dignity, not mentioning Islamic principles and etiquette – why are we copying methods that seem to ‘work’ when they produce injustices?

One other example is the use of distressing pictures of starving children during fundraising dinners. This technique is copied from white American Evangelists – those who like to turn the Sunday masses into giant TV shows – and boasts a very pervasive yet effective way of obtaining funds: through guilt. The method is exactly the same: in the middle of a non-related religious event (which could be about anything from marriage or fiqh to Islamophobia or philosophy), the talk is suddenly interrupted by a heartbreaking video of amputated or sick people crying, often with children, accompanied by a tear-shedding melody before an army of volunteers harvest the audience’s rows with donation buckets. I will not even mention the commercial rhetoric that ‘your donations are building you a castle in Jannah’. Not only does it use, without any dignity, people affected by diseases as fundraising tools, but it also perpetuates this binary and simplistic narrative of the North having to help the desperate South. Perhaps organisations’ fundraising officers have found that guilt raises more money than love, care or trust, but first, it would be worth researching if historically Zakat and Sadaqa were collected by making people feel horribly guilty.

Many would point out in their defence that charities need social media for promoting their projects, and that these kind of selfies are what works best – or what everyone does. However, the problem does not lie with social media itself, but rather how we use it. Furthermore, it is possible to find a middle-way. If we look at small grassroots Muslim charities, there is a way of being effective without sacrificing ethics. Rumi’s Kitchen or Children of Adam in London are leading examples: they have a no-selfie policy, they don’t use high-visibility jackets (not to create a division between volunteers and beneficiaries) and they promote conversation between volunteers and beneficiaries. Their communication on social media is minimal, organic and yet it works. Many more examples exist to show that it is not necessary to copy everything modern society produces to actually make a difference.

So, what strategy for large charities? For those sending volunteers abroad, SAIH’s guide offers some practical solutions:

- Promote dignity: avoid propagating stereotypes (like depicting areas you visit as plagued by war, diseases and poverty – we have the DailyMail for that)

- Gain informed consent: did you ask for their authorisation?

- Question your intentions: why do you travel? Are you making yourself the subject or the issues you are seeing?

- Bring down stereotypes: portray people in ways that enhance connection: ask about their life stories or anything they would like to share.

On the other hand, it is understandably difficult to escape these behaviours when large charities are caught in a race for numbers. When people define success in terms of money, Facebook likes, retweets and YouTube views, enough will never be enough. The multi-million pound/dollar Muslim charity industry has traditionally been focused on projects abroad. It is incredibly important knowing that Muslims in the West donate generously; however, it is fundamental to take into account that the young and upcoming generations are more concerned about local problems such as homelessness, children and single parents in poverty, Islamophobia, mental health and more – the recent Grenfell tower tragedy demonstrated this noticeably. Research has shown that people give and commit more sustainably to causes they can relate to, and for which they can actually see that they make a difference. It is perhaps time for big charities to rethink their strategies and focus on more relatable local issues so people can dedicate resources out of trust rather than guilt.

On a final note regarding the fetishisation of poverty, while Islamophobia is prevalent, we don’t need more media attention for replicating problematic behaviours. Most importantly, as Muslims, while we boast so much about our ethics being respectful of people from any ethnicity, culture, religion or class, shouldn’t we pave the way for showing what the best practices are?

by William Barylo