Although Afghan culture and heritage have without a doubt been scarred by colonial enterprises, violence, and extremism, it remains a country infused with a multiplicity of traditions, both pre-and post-Islamic.

Although Afghan culture and heritage have without a doubt been scarred by colonial enterprises, violence, and extremism, it remains a country infused with a multiplicity of traditions, both pre-and post-Islamic.

This article was originally written for Ajam Media Collective by author Felix de Rosen. You can find the original article here.

The sun was up. After a night of cool, fresh temperatures, I feared the sun; it would not take long before the August air became an oven. For the time being, everything was at peace. The city had been awake and buzzing for at least an hour already, since the dawn prayer. The staggered rev of scooters and cars replaced the silence of the evening, but only gradually.

“The breeze at dawn has secrets to tell you.

Don’t go back to sleep.

You must ask for what you really want.

Don’t go back to sleep.

People are going back and forth across the doorsill

where the two worlds touch.

The door is round and open.

Don’t go back to sleep.”

(The Breeze at Dawn, Rumi)

I left the steps of the Aria Hotel, my cheap hostel in Mazar-e-Sharif, carrying some money, my camera, and my Persian-English dictionary. The Aria Hotel sits on the city’s main square, whose focus is the wonderfully immaculate Shrine of Hizrat Ali (Rawz-e Sharif). The shrine is generally considered Afghanistan’s holiest site and is one of the reputed burying places of Imam Ali; its azure and ochre tiles reflect the sun’s light stunningly at any time of day.

I walked four blocks west of the square, sending small waves of dust with each step. From here, shared taxis leave for the city of Balkh, located about 45 minutes west.

If Mazar-e-Sharif is the economic capital of northern Afghanistan, Balkh is the country’s ancient, albeit decaying, heart. It was long the center of the Zoroastrian world, being the birthplace of Zoroaster, although the growth of the Persian Empire eventually moved the heart of Zoroastrianism westwards into Persia.

Buddhism also left its mark on Balkh, interacting with and influencing Zoroastrian thought. Xuanzang, the Chinese Buddhist itinerant monk, travelled to Balkh in the 7th century CE and, in his memoirs, wrote that there were around a hundred Buddhist convents in or near the city, as well as over 30,000 monks and a large number of stupas.

The city’s rich Sufi tradition has undoubtedly been influenced by Zoroastrian, Buddhist, and animist elements over the years. The most celebrated Persian-language poet, Jalal ad-Din Muhammad Balkhi, also known as Mawlana in Iran and Afghanistan and as Rumi in the English-speaking world, was born in Balkh in 1207 AD. Rumi’s major work is Matnawiye Ma’nawi (Spiritual Couplets), a six-volume poem of over 27,000 lines regarded by many Sufis as the Persian-language Qur’an.

But Rumi is not the only poet from Balkh. Rabia Balkhi, one of many female Persian-language poets, according to legend, wrote her final poem on her bathroom wall using her own blood, before dying:

“I am caught in Love’s web so deceitful

None of my endeavors turn fruitful.

I knew not when I rode the high-blooded stead

The harder I pulled its reins the less it would heed.

Love is an ocean with such a vast space

No wise man can swim it in any place.

A true lover should be faithful till the end

And face life’s reprobated trend.

When you see things hideous, fancy them neat,

Eat poison, but taste sugar sweet.”

There is also a lesser-known figure who lived in Balkh. Part legend, part history, Baba koo-i Mastan, the divine madman, was “a pre-Islamic holy man from Bactria…credited with being the first to refine hashish, and his tomb near Balkh is still visited by locals and tended by a dope-smoking malang (holy man)” (Lonely Planet Afghanistan, p. 155).

I was intrigued, and without any information as to the whereabouts of the tomb, I proceeded to ask people on the streets.

I stepped out of my shared taxi onto Balkh’s main street. Balkh had a completely different feel from Mazar. Mazar was a modern urban center, destroyed partially over the last forty years and now rebuilt with unattractive concrete buildings. Balkh, on the other hand, felt like an oversize village. Trees provide shade throughout most of the city. The park at its center is filled with men and women socializing (separately), sitting on the ground, or reclining on whatever’s around.

Outdoor restaurants around the park fill the air with the scent of kebab and moist rice pilaf (pulao). Crumbling mosques and an abandoned fortress let the mind recreate the city’s former grandeur.

I decided to seek out Baba koo-i Mastan. As I asked for the whereabouts of his tomb, I received many confused looks, but the general consensus was to walk south. I reached the ancient city walls, a 12 kilometer-long massive structure that used to protect the city but is now abandoned.

Eventually, I arrived at a small clearing on the side of a road, separated from the road by a waist-high mud wall. Inside the clearing was an enormous grape tree with an array of red ribbons tied to its branches, a small tomb on the ground surrounded by a blue fence, and a short man who called himself Ali.

I asked Ali if this was Baba koo-i Mastan’s tomb; he confirmed that it was and that he was its malang. I had expected an ancient tomb, placed in a building with lots of shade, filled with smoke, surrounded by trees, and with a scattering of devotees waiting for their turn to speak with the malang. Instead, I found a clearing on the side of a busy road with a malang who asked me how much I would sell him my camera for.

Ali wore the shalwar kameez, rings on five of his fingers, a couple of old pendants, and a pink scarf draped over his left shoulder. Ali and I sat and talked. He climbed the tree to get us some grapes. The leaves of the tree were covered in a fine white dust, collected over many years alongside a busy road.

Ali was young, in his mid-twenties, although he could pass for forty. How did he make a living I asked? He lived off of donations, tending to the tomb and giving advice to locals. He had a wife and four children. As we spoke, two of his daughters approached us silently. He kissed them and told them to go home, a small house a couple feet away.

I was interested in learning about his religious perspective. Did he “choose” to be a Sufi? How did hashish fit into the story? I was limited by my deficient Farsi, but I did manage to understand a little. Ali explained, very slowly so that I had enough time to look up the words he used in my dictionary, that Balkh and the surrounding region has a rich Sufi tradition that evolved from the region’s many influences: Islamic, Buddhist, Zoroastrian, animist, etc. Balkh’s legendary rulers, poets, and mystics are products of this diverse history.

Although Rumi and Rabia Balkhi are long gone, the spiritualism, drama, and poignancy of their words have not been eradicated by Afghanistan’s troubled history (See here for a detailed overview of Afghan mysticism).

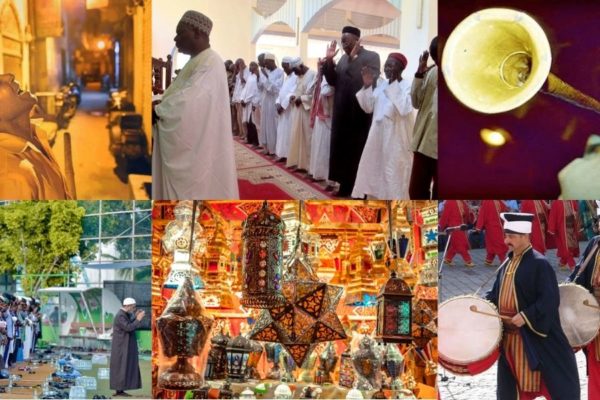

Although Afghan culture and heritage have without a doubt been scarred by colonial enterprises, violence, and extremism, it remains a country infused with a multiplicity of traditions, both pre-and post-Islamic. These emerge in the sensuous lines of legendary Persian poets, in the celebration of Persian New Year Nauruz on the spring equinox (a Zoroastrian tradition), and in the sport of buzkashi, whose origins in nomadic culture are easy to behold.

The tomb of Baba koo-i Mastan is but one example of Afghanistan’s rich heritage. Ali became malang when his teacher, the previous malang, died; he is Baba koo-i Mastan’s living legacy, preserved through time and a tradition of direct lineal descent. Ali looked at me intensely and said with an enormous smile, “I am crazy. Watch out!”

Our conversation unhurriedly slowly, marked with pauses in which we would observe the carts, cars, and people moving at their respective speeds on the road. During a break in our conversation, Ali took out a dark brown chunk of hashish and we moved to a small alcove alongside the tomb so that he could smoke (and continue talking all the while).

My dictionary and limited knowledge of Farsi were insufficient to understand Ali’s more abstract thoughts, and I told him this and he smiled back. His smile, which was both mischievous and innocent, laughing at me but inviting me in. Ali sang a few songs. At one point, a friend of Ali’s stopped by and joined us. We had a good time taking pictures of ourselves. I felt like I was hanging around with an old friend, but the old friend was Ali, the malang. The absurdity of the situation made me laugh and the beauty of that absurdity made me smile.

Tired and feeling the full force of the midday heat, the afternoon’s pleasures caught up with me and I decided to head back. I thanked Ali and left. I sat sleepily in a restaurant on the main park, re-energized by pilaf and a coke. The streets were quieter now. Everyone was in the shade, avoiding the sun. Donkey-carts clopped their way down the street, alongside the usual loud scooters and rumbling cars. I took a shared taxi back to Mazar and fell asleep under the lofty ceiling of the Aria Hotel, thinking of Rumi’s words (translated quite loosely):

Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing, there is a field.

I’ll meet you there.

When the soul lies down in that grass,

the world is too full to talk about.

Ideas, language, even the phrase each other

doesn’t make any sense.

از کفر و از اسلام برون صحرائی است

ما را به میان آن فضا سودائی است

عارف چو بدان رسید سر را بنهد

.نه کفر و نه اسلام و نه آنجا جائی است