Today, listening to his recordings we are struck not only by the beauty of his song but also by the power of his voice to convey the deep sense of connection he managed to recover against the modern narratives of bounded nations, civilizations, and continents.

Today, listening to his recordings we are struck not only by the beauty of his song but also by the power of his voice to convey the deep sense of connection he managed to recover against the modern narratives of bounded nations, civilizations, and continents.

This article was originally written for Ajam Media Collective by author Stefan Williamson Fa. You can find the original article here.

In the latter part of the 19th century, the British colony of Gibraltar became a hub for Sindhi merchants from the Indian Subcontinent who travelled across new routes opened up by the Suez Canal – from Karachi to Aden, Cairo, Malta, and across the Mediterranean. The expansion of Sindhi owned textile-businesses on the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula ensured a relatively steady flow of mostly male merchants and workers to the colony.

For one individual from Sindh, moving to Gibraltar became an opportunity to pursue a spiritual and musical path. Aziz Balouch, a young singer and Sufi devotee, went on to dedicate his life to the exploration of the deep connections between the Andalusian music of southern Iberia and the Islamic past.

Based on his writings, recordings, and other unpublished archival material, in this essay I trace his path as he travelled first from modern-day Pakistan to Gibraltar and later between London and Madrid. Although he remains relatively unknown, his work was a pioneering effort to uncover and celebrate the Islamic roots of Andalusian music while his extraordinary life reveals a complex and rare story of music, movement, and mysticism across continents in the 20th century.

Azizullah Khan Al-Zahidi was born in Baluchistan in 1910. Following his father’s sudden death, he was sent to Sindh to study at the madrasa of the Pir Pagaro dargah. Here his formal education was enriched by hours at the shrines of Sindhi saints, including that of Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai, where he was first exposed to Sufi poetry and music in the chants of devotees.

When Balouch moved to Hyderabad to study and work, he had his first taste of flamenco, the folk music of southern Spain. He was introduced to the genre when listening to the record collection of a close Hindu Hyderabadi who had a business in Gibraltar. He was immediately enamoured and “spiritually uplifted” by the voices of the singers he heard. This discovery of Spanish music and his interest in the history of Al-Andalus, and particularly its philosophers, poets, and mystics like Ibn Arabi, meant that he did not think twice when his friend offered him a job in Gibraltar.

In July 1932 Balouch left Karachi for the Iberian Peninsula. “We arrived at Gibraltar, the historical ‘Jabal al-Tariq’” he writes in his memoirs “when I beheld the Rock and the Castle of Tariq, the frontiers and the first vistas of Southern Spain, I felt like one returning to his own land.” Despite this romantic arrival on the Rock, his first year in Gibraltar was spent working long hours in a shop on Main Street. He had to wait a year before he experienced flamenco live – an encounter that would change the course of his life.

Balouch attended a live concert by the most renowned contemporary flamenco artists across the border in the Spanish town of La Linea, which included singers such as Pepe Marchena and La Niña de los Peines. Ecstatic about the performance he insisted his friends invite the artists to Gibraltar the next day as he wished to sing for them. Accepting this odd request, the artists visited the business premises where Balouch performed a number of flamenco pieces and Sindhi songs accompanying himself on a harmonium.

Delighted by the short recital, the singer Pepe Marchena invited Balouch to perform on stage the following evening. Balouch gave a rendition of Marchena’s own song ‘La Rosa’ which proved so popular he was apparently recalled for an encore seven times. Following this success, which the Gibraltar newspapers hailed “An extraordinary event in the history of flamenco”, Marchena agreed to take on Balouch as his student. Soon, Balouch adopted the moniker “Marchenita”- Little Marchena.

Balouch continued working in Gibraltar but moved to Madrid a year later to dedicate himself entirely to flamenco. His reception here was mixed. Some, including Marchena himself, were truly impressed and inspired by his talent and passion for the genre while others took him less seriously and saw him only as an ‘exotic’ and humorous curiosity. Concert posters often billed him in an orientalist manner “THE INDIAN who sings flamenco, disciple of Marchena, with his MAGICAL INSTRUMENT”.

Various concert and radio appearances led to an invitation to record a number of songs. His only catalogued record, Sufi-Hispano-Pakistani, was a first on many levels. It was unprecedented for a young man from South Asia to record an album in Spain and it was also the first example of experimentation and ‘fusion’ in flamenco. The record seamlessly blended Persian, Sindhi, Arabic, and Hindi poetry with the melodies and lyrics of Andalusia.

In one track, he begins with the Persian poetry of 12th-century poet Sanai before transitioning into the expressive mood of the seguiriya.

ملکا ذکر تو گویم که تو پاکی و خدایی

نروم جز به همان ره که توام راه نمایی

Oh King, I sing your praise, for you are pure and regal

I shall not fare except on the path that you have pointed out to me

Ahora tú vienes hincá de rodillas pidiendo perdón,

te apartaste de mi vera y te fuiste sin apelación.

Now you come to me on your knees begging forgiveness,

You left my side ignoring my appeals.

The outbreak of the Spanish Civil War forced Balouch to cut short his time in Madrid and seek refuge in London. Although his obsession with flamenco did not fade, Balouch dedicated most of the next decade in London to promoting Sufism. In 1948 he founded the “Sindh Sufi Society” “to propagate the ideas of Sufism, a soul-purifying philosophy of the East.” The interest in theosophy, spiritualism, and occultism at the time meant that London provided a fertile ground for the propagation of his ideas. He organised regular events, writing, and publishing from his small home in Notting Hill, West London.

In the inaugural meeting of the Sufi Society on the 12th December 1948 Balouch gave an introductory lecture on Sufism and a performance of Shah Abdul Latif’s to a crowd of friends from Spain, Morocco, Bombay, and Trinidad. Subsequent meetings explored different topics and included a session on “The Sufis of Persia and their influence over the spiritual and literary world”, with a lecture by Mr. M. Minovi, an Iranian critic and writer, and a musical performance by Prince F. Farhad, which included songs by Hafiz and Rumi accompanied on the tar.

From the breadth of these events and available correspondence, it is clear that Aziz Balouch attracted the attention and interest of a wide range of personalities from European musicians to established intellectuals from South Asia living in London.

Balouch was invited to return to Madrid in 1952 by the newly-appointed Pakistani Ambassador to Spain, Syed Miran Mohammad Shah. Here, he was given the role of Cultural Attaché at the new Embassy of Pakistan. With embassy support, he founded an association called Amigos de Pakistan and continued to perform alongside Pepe Marchena and alone across Spain. His performances now aimed to demonstrate the similarity between flamenco and the “profound singing” of Sufi songs.

Press reports attest to the general acceptance and appreciation of Aziz Balouch’s theory and work, all the more impressive given the context of General Franco’s insular nationalist dictatorship. Balouch’s tenure at the Embassy ended following Shah’s departure but he continued to promote the connections between Spain and Pakistan in a personal capacity, in his book Cante Jondo su Origen y Evolucion – Cante Jondo Its Origin and Evolution (1955).

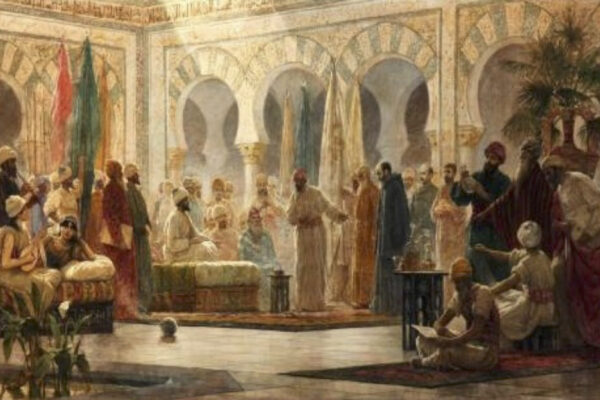

In this book Aziz Balouch offers several different possibilities for the connections between Spanish and Sindhi music, most going back to the period of Muslim rule in Spain. He argues that Sindh and Andalusia were conquered by Muslims at roughly the same time allowed for the relatively uninterrupted flow of music and culture across Muslim lands. He claims that the influential medieval composer Ziryab was of Sindhi origin and was the first to introduce Cante Jondo to the Iberian Peninsula from the subcontinent. Perhaps more credible, however, given recent research on the topic, is his suggestion that the gitanos, Romani in Spain, originate in South Asia, therefore bringing elements of their musical culture with them.

The book draws several parallels between the two musical traditions and compares certain forms of these in depth. For instance, Balouch compares the saeta, a lament sung in Andalusia during Holy Week, with the marsiya recited to commemorate the martyrdom of Imam Husayn. He writes:

“Just as in Spain, the songs in the Holy Week are sung in processions without instrumental accompaniment except the drum, so are the marsiya in Sindh as well as in other parts of Pakistan sung only to the accompaniment of a drum. The most typical of these songs, falling within the general category of the marsiyas sung exclusively in the Lower Indus Valley of Sindh, are known as Osara. The semblance between the Osara of Sindh and the Saeta religious songs of CanteJondo is typical.”

Despite the general lack of evidence provided for his claims, the book marks a pioneering attempt not only to trace a connection between flamenco and Spain’s Islamic past but also to celebrate it. The significance of this work can be appreciated in the more recent growth in ‘fusion’ projects and literature which support Balouch’s narrative. Some of these projects, including Tony Gatlif’s 1993 film, Latcho Drom, have attempted to trace Romani routes from South Asia to the Iberian Peninsula. Others, such as Faiz Ali Faiz’s Qawwali-Flamenco (2006) or Kudsi Erguner’s merging of flamenco and Ottoman music in the album L’Orient De L’Occident (1995) have focused on the genre’s ‘Islamic roots’.

While similar productions have also achieved popular, commercial, and critical success they have often represented a fairly superficial and unequal engagement across musical boundaries geared towards ‘world music’ consumers.

Aziz Balouch’s life offers an important testament of musical encounters across borders before the dawn of commercial ‘fusion’ productions or the academic discipline of ethnomusicology. Unfortunately, within Spain, his legacy remains that of a curious episode in the history of flamenco and in the UK, Gibraltar, or Pakistan few know his name. Guided by a profoundly instinctive feeling of connection with the music he loved, Balouch was clearly not interested in the search for an objective historical truth.

Today, listening to his recordings we are struck not only by the beauty of his song but also by the power of his voice to convey the deep sense of connection he managed to recover against the modern narratives of bounded nations, civilizations, and continents.