Mainstream Muslim academia finds power in Arab and Southeast Asian narratives.

Mainstream Muslim academia finds power in Arab and Southeast Asian narratives.

In The Race for Timbuktu Frank Kryza describes Timbuktu as a “nexus, a bridge – the only one, in fact” between Black Africa and the Arabic speaking North Africans. Joshua Hammer in his book The Bad Ass Librarians of Timbuktu, calls Timbuktu a regional center of scholarship and culture. Timbuktu, although not unique in the history of Black African Muslim cities, has seen a bit of revival in the news and scholarship as of late. Abdel Kader Haidara, a Malian librarian and archivist, set on on the task of traveling throughout Mali, looking for manuscripts from the “Golden Age of Mali.”

In 2012, Sharia law was imposed on North Mali by Al-Qaeda, and similarly to what is happening in Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan, historical and cultural artifacts were destroyed including Sufi shrines and massive book burnings of Malian manuscripts. Many who were in possession of these manuscripts would make the daring decision to hide their literary treasures from the extremists. If caught it was certain they would be punished with lashings or even death. Haidara, in search of these manuscripts to preserve and catalog, would travel by air, water, and road in search of these manuscripts. Knocking from door to door in remote villages, working off tips and gossip in the local market Haidara and his team made amazing strides. In nine months Haidara and his team were able to save over 350,000 manuscripts from forty-five different libraries in and around Timbuktu.

Charlie English in his book Book Smugglers of Timbuktu confronts the age-old myth that Black Africans lack culture. He calls out the likes of David Hume and Georg Hegel as they have both referred to Black Africa as a place “without history.” A place that can neither be plundered or cultivated because of the lack of history. As English points out, Timbuktu and many other Black African cities operated as a “Cambridge of the Sands.”

The New York Times ran an article in May of 2017 titled Treasures of Timbuktu detailing the work that Haidara and his team are doing at the Ahmed Baba Institute in Timbuktu. The very next month The New York Times published a book review for The Quest for Timbuktu and the Fantastic Mission to Save its Past. The Statesman has even published articles on the bravery of the collectors who saved the manuscripts and the librarians who sought to preserve them.

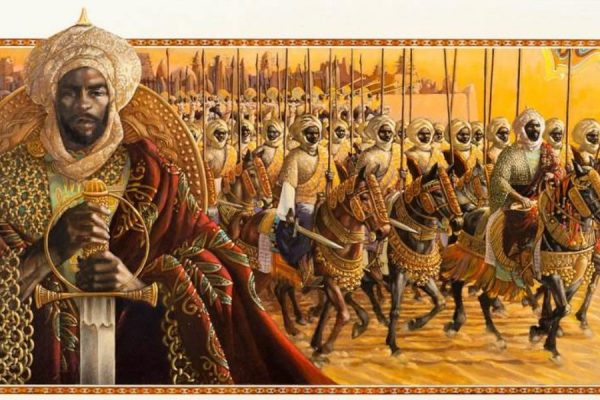

The story of Haidara and the librarians who saved the manuscripts seems to have captivated the non Muslim Western world, again. Timbuktu, known as the “African El Dorado” by European explorers in the 1600s looking for gold and other treasures, was a place of mystery for them. Tales of Mansa Musa’s splendid Hajj journey where he gave gold away wherever he went found their way to Europe. The image of Mansa Musa sitting with his legs crossed holding a golden nugget by a Florence mapmaker was a product of the European imagination, not reality. Although Mansa Musa is the wealthiest person in history, where his wealth was, was uncertain. Europeans believed that Timbuktu was the source of gold, but in reality it was a trading city where gold was sent, not mined.

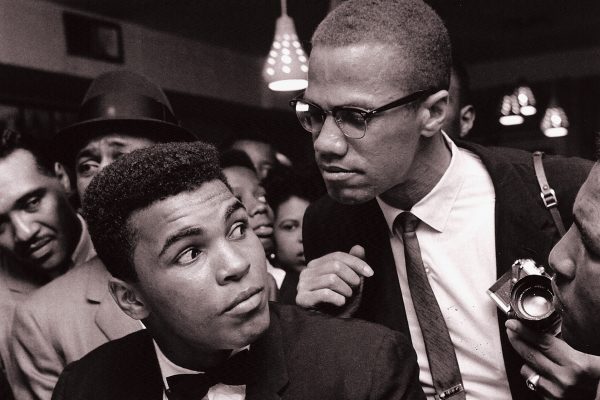

Today, books, articles, and even documentaries have been produced on the work that Malian archivist, historians, and librarians are doing with the manuscripts. It seems though that on the other hand, the manuscripts have not captured the attention of mainstream Muslim academics. One would imagine unearthing thousands of works on Islam would cause a twitter storm by the likes of Imam Suhaib Webb or Yasir Qadhi. The rush to support Black Muslim history from two major Muslim scholars has not come. Maybe a retweet of a Malcom X quote during Black History Month, but other than that, nothing.

Mainstream Muslim academia finds power in Arab and Southeast Asian narratives. Persian and Turkish sources also hold great weight in Muslim academic circles. To add some historical context, The Mali Empire was established in 1230 and the Ottoman Empire established in 1299. Arabic flourished in both empires and both left a profound amount of history. The Ottoman Empire holds more prestige and authority in Muslim academic circles. There is work that Malian jurists, poets, and leaders left for us, the issue is it is not being shared by the gatekeepers of Muslim academia. Adding the thousands of Black Muslim intellectuals to the catalog of creditable historical sources of sharia law would be a task. It would also shift the power balance of academic hierarchy, but it must be done.

There is no reason to keep ignoring the rich and important history that Black Muslims have within Muslim academic history. There is no reason to ignore Al-Mukhtar ibn Ahmed who wrote a letter to warring tribes giving them advice from the sunnah and Qur’an to lay down their arms and end their war. There is no reason to ignore Ahmad ibn Amar, a doctor who wrote Curing Diseases and Defects both Apparent and Hidden. There no reason to ignore Ahmad ibn Sulayman who wrote Explanations of Problems in Arithmetic and Examples. Why ignore the mother of the Mali Empire, Sologon who carried her son Sundiata from village to village, seeking protection for her son who at the age of eighteen would unite the warring tribes and establish the Mali Empire? The work of these towering figures in Muslim history is there and available, it is time to take these works seriously.