The Ar-Razzaq community thus crafted a foundation for generations of Muslims within and beyond the Black Muslim community.

The Ar-Razzaq community thus crafted a foundation for generations of Muslims within and beyond the Black Muslim community.

It is a recognized fact that the United States has been profoundly shaped by the experience and contributions of Black Muslims. Yet the retelling of Black Muslim history is often missing from public educational spaces. Thus it is a welcome surprise that a small history museum in the south, Museum of Durham History, also known as the “Museum Without Walls,” has committed itself to retell the history of Black Muslims in Durham, North Carolina. Its current exhibit “Building Bridges through Good Faith” highlights the history of Ar-Razzaq Islamic Center, the oldest mosque in the state of North Carolina. Inspired by the Museum’s earnest interest in partnering with local communities, Sister Naomi Shakir Feaste, community leader and member of Ar-Razzaq Islamic Center since 1971, suggested the idea of featuring Ar-Razzaq. Sister Naomi wanted to offer a positive envisioning of Islam in America that greatly differed from the countless stories of extremism that all fail to represent her faith and identity as a Muslim. In fact, it was mainly due to her desire to combat harmful stereotypes about Muslims that Sister Naomi worked with MODH curator, Katie Spencer, to curate the Ar-Razzaq exhibit and explain their process on WUNC’s program ‘State of Things.’

The exhibit features vibrant artifacts spanning the founding history of Ar-Razzaq. A photograph entitled “Planting Roots in the West End,” shows one of the mosque’s more prominent members and renowned jazz musician, the late Yusuf Salim, posing with smiling neighborhood youth who participated in Ar-Razzaq’s “Clean-Up Squad.”The Clean-Up Squad was an initiative on the part of the mosque to beautify Durham’s West End neighborhood the children who participated were nurtured and fed through the community’s food program.

Salim organized the “Clean-Up Squad” and served as a dishwasher in Ar-Razzaq’s adjacent Shabazz Restaurant and Bakery. The community rooted itself in charitable programs, and its restaurant and bakery were important avenues through which members also conducted outreach to the broader community. This legacy of provision and care continues today. During the summer, Ar-Ar-Razzaq feeds thousands of children daily through its lunch programs. In addition, it contributes heavily to refugee relief and provides educational opportunities for adults, children, and the broader community.

The exhibit offered personal photos, keepsakes, recipes, and oral histories capturing the legacy of Ar-Razzaq Islamic Center. The opening reception hosted scores of community members who converged on the bright, welcoming space to learn about the men and women who helped to establish an Islamic presence in the American South.

Participants shared old memories, met new friends, and tasted samples of bean soup and the community’s treasured bean pie. Yet the power of this exhibit is in its interactive digital collection of interviews. Over the course of a year, researchers and community volunteers collected personal narratives, photos, and artifacts to creatively document and share the stories of countless members of the Ar-Razzaq community by highlighting its economic, social, political, educational and cultural impact on the city of Durham.

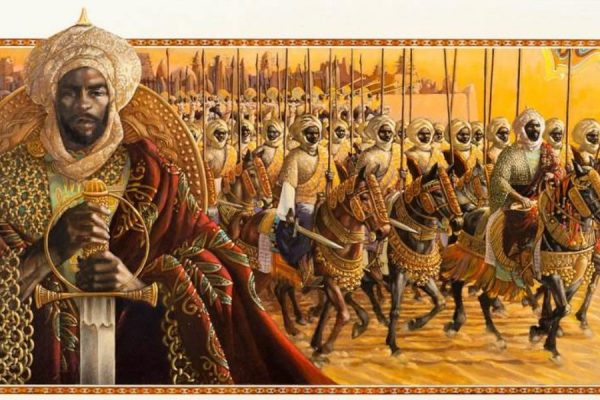

Patrick Mucklow, Executive Director of the museum, credited the exhibit with increasing his own awareness of Ar-Razzaq’s legacy in Durham as well as the legacy of African American Muslims in the United States more broadly. In commenting on why Ar-Razzaq Islamic Center was chosen by the Museum to highlight, Mucklow says, “We felt that the story of Ar-Razzaq was important because of the impact and contributions on not just the West End neighborhood, but on the city of Durham as a whole. The community introduced new foods and traditions to Durham, gave jobs to locals, established a vibrant cultural presence, and is an anchor institution in one of Durham’s oldest neighborhoods. Those who grew up in the Ar-Razzaq community have become parents, entrepreneurs, public servants, citizens and neighbors who bring the values of their upbringing to Durham and the world. The longevity of the community is a testament to the strong foundation built by its founders in its early years. We wanted to show that Muslim presence in the United States is at least as old as European contact, that one-third of Muslims in the U.S. are African American, and have been here for generations. Of the many Africans brought to America and enslaved, historians, estimate that anywhere from 10 to 33 percent were Muslim.”

His testimony provides us with a glimpse of the importance of both documenting and sharing the Black American Muslim historical experience. Meanwhile, Sister Naomiasserts that the historical and current significance of the mosque is also vitally connected to its name and mission. ‘Ar-Razzaq’ which loosely translates as “The Provider” signifies one of the attributes of a Merciful Creator. Just as humanity gets its provision from Allah, Ar-Razzaq Islamic Center has consistently understood itself as a community that has a responsibility to provide for others, particularly those who are less fortunate.

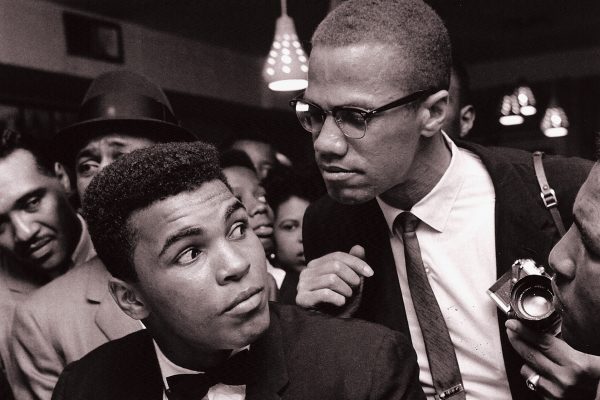

The beige and purple displays at the exhibit reveal to its visitors that since its inception in the late 1950s as Muhammad’s Mosque No. 34 (when it was a Nation of Islam-affiliated mosque), the Ar-Razzaq Islamic Center has long been a bastion of relief and provision for its members as well as Durham’s West End community. Kenneth and Margaret Murray Muhammad, founders of the mosque, arrived in Durham as the city was immersed, as was much of the South, in the question of how to deploy the right of equal treatment that African-Americans were demanding from their local and state governments. In fact, the exhibit situates Ar-Razzaq in that history by opening the narrative with the famous 1963 James Baldwin photograph in which he stopped in front of a storefront window to write in his notebook. That storefront window read “Muhammad’s Mosque,” the place of worship and service that Kenneth and Margaret Muhammad opened in Durham in order to give life to what is now a modest, but vibrant community of African-American Muslims. During this time of social and political tension in the American South, Durham’s Black Muslim community firmly established itself into the fabric of the city as a place of worship where its members learned the value of public service.

It is in this context that what was possibly the state’s first Islamic school was established within the walls of the mosque. Proof of this fact is found in the tiny, brown faces that beam in a photograph of the mosque’s primary school. The photo taken in the 1980s shows students in khimars and hand-sewn school uniforms with several teachers of the Sister Clara Muhammad School at the Ar-Razzaq Islamic Center. The Muslims who were the fuel for mosque activity understood that education was vitally connected to economic self-determination and nation-building. It is with this in mind, that the Museum of Durham History commemorates the enduring presence of Durham’s Black Muslim community with inviting displays that connect the founding of the mosque with the long history of Islamic presence in the United States before the founding of the country itself. The Ar-Razzaq community thus crafted a foundation for generations of Muslims within and beyond the Black Muslim community. As the nation continues to grapple with the reality of its Muslim citizenry, this exhibit documents a valuable history, a story of spiritual commitment, and the deep legacy of Black American Muslims.