Of course, it remains necessary to consciously condemn anti-black racism, just as we would expect non-Muslims to condemn Islamophobia. But we must go further. We need to interrogate subconsciously anti-black attitudes, whether they manifest in systems or structures, in our communities, or even in our own minds.

Of course, it remains necessary to consciously condemn anti-black racism, just as we would expect non-Muslims to condemn Islamophobia. But we must go further. We need to interrogate subconsciously anti-black attitudes, whether they manifest in systems or structures, in our communities, or even in our own minds.

Cities across the US are ablaze with protests as swathes of people express a visceral sadness and anger at the killing of George Floyd at the hands of the US policemen Derek Chauvin.

What can drive a human being to kill another purely on the basis of the colour of their skin? Every non-black person must ask themselves this. The answer is decades and decades of subconscious racism, incepted initially by the historical events of yesteryears, and maintained and propagated by systems and structures of power.

Here is where we can realise the flaw in our narrative around anti-black racism. It is tokenism. A hashtag. A retweet. These easy and effortless platitudes are perhaps more for earning the currency of likes and shares in the economy of social media. With our egos pleased, we hardly stop to think how such a situation transpired in the first place, and then meaningfully change our own hearts and minds.

Society first accepts divisive words. Words are like a tree; when a seed is planted, the fruit of the tree is but a reflection of the seed. If the seed is malice, the fruit will be malicious. The skin of this fruit may be thick, painted by the causes of ‘homeland security’, ‘economic interests’, ‘higher rates of crime’. Government, media, and elements of civil society utilise these discursive frames to discuss black people.

To those whose necks are not being pressed by the knee of structural racism, these might seem like reasonable ways to discuss black people. For the same people, it slowly seems justifiable to accept the divisive treatment of black people. The proliferation of these racist and analytically flawed discursive frames makes it seem justifiable too, for example, to stop and search black people, engage in passive-aggressive questioning, and to fire looks of distrust and suspicion.

Such behaviour slowly becomes normalised. Seemingly well-intentioned non-black people who consciously do not agree with racism slowly begin to see anti-black racism as, at best, unremarkable or normalised, and at worst, justifiable.

Other ethnic minorities are also susceptible to this alongside the ethnic majority. The idea that other minorities cannot be racist is simply wrong. We all belong to a tribe, and so we all have an idea of ‘us’, and therefore can easily construct an essentialised conception of ‘them’. As a South Asian, I have seen ugly anti-black attitudes being routinely spouted. I have even overlooked casual anti-black racism, evidently being subconsciously swayed by anti-black rhetoric.

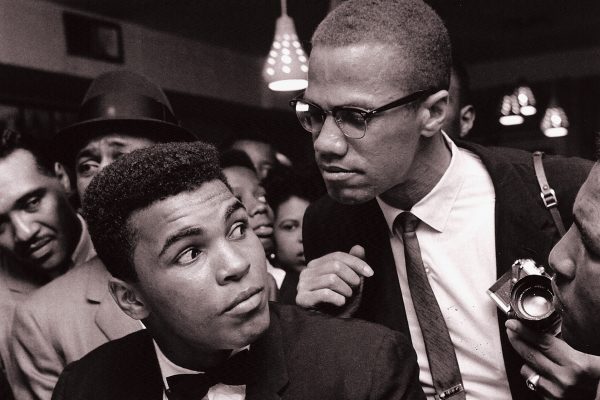

The far extent of this subconscious racism is truly terrifying. Mr Ostrowski, Malcolm X’s white English teacher asked, Malcolm about his career plans. Malcolm replied that he wanted to be a lawyer. Mr Ostrowski replied “[a] lawyer – that’s no realistic goal for a n****”. Yet Malcolm was convinced that his teacher “probably meant well” and that he liked Malcolm. Here, it becomes evident that being consciously not-racist is meaningless if one is beholden to overbearing subconscious racism. Explicitly saying that you are against racism is not a sufficient condition to save yourself from being racist.

A further example of the impotence of conscious non-racism in the face of wider structures of hate is Simon Wiesenthal’s encounter with a repentant Nazi. Simon Wiesenthal was a prisoner in a concentration camp, and he was asked by a dying Nazi soldier for forgiveness for what he had done to Jews. The soldier explained how he lamented that he had killed Jews on two occasions. He was wrought with guilt. Wiesenthal later wrote in his memoir that most Nazi soldiers were not born murderers, they became murders. In the case of the dying soldier, he even consciously believed that what he was doing was wrong, which is why he asked for forgiveness. But that did not stop from the overwhelming structures of anti-Semitism from overpowering him into contributing towards genocide.

It follows, then, that for non-black people, consciously condemning anti-black racism is insufficient. Of course, it remains necessary to consciously condemn anti-black racism, just as we would expect non-Muslims to condemn Islamophobia. But we must go further. We need to interrogate subconsciously anti-black attitudes, whether they manifest in systems or structures, in our communities, or even in our own minds.

The best way that we can go about this is to increase ourselves in taqwa, reverential consciousness of Allah. When you look upon people different to yourself, realise that they too are Allah’s creation, and are ennobled and honoured by their mere existence. As Muslims, we are obligated to uphold justice. We can never accept the murder of an innocent soul purely upon the colour of their skin. That is a filthy aberration, wholly disgraceful and unjust.

If you do not feel irked or outraged by the murder of George Floyd, then you need to work on yourself. Read, study and think about the struggles of others. And more importantly, we should all to pray to Allah that our hearts never tire in challenging injustice.

“People, We created you all from a single man and a single woman, and made you into races and tribes so that you should recognize one another. In God’s eyes, the most honoured of you are the ones most mindful of Him: God is all knowing, all aware.” – Surah Hujurat, Verse 13.