“For these last days have brought us rumours of an attack upon you Liverpool Mussulmans by a section of the ignorant populace. This attack and maltreatment can but awaken afresh our sincere friendship toward you all. Should you have a journal specially treating of your Institute, kindly inform me, and I shall subscribe to it, so as to be in a better position to reassure the minds of our coreligionists in the East.”

An Early Arab View of Liverpool’s Muslims: Al-Ustadh and Sheikh Abdullah Quilliam During the Age of British Imperialism

“For these last days have brought us rumours of an attack upon you Liverpool Mussulmans by a section of the ignorant populace. This attack and maltreatment can but awaken afresh our sincere friendship toward you all. Should you have a journal specially treating of your Institute, kindly inform me, and I shall subscribe to it, so as to be in a better position to reassure the minds of our coreligionists in the East.”

As not much is known about how Sheikh Abdullah Quilliam (1856-1932), the founder of England’s first mosque and the first imam, was viewed outside of Britain in the Ottoman Empire, Africa or Asia, I have great pleasure to introduce and present for the first time a translation of an early Arab eyewitness account of the Liverpool Muslims from 1892 (but published in 1893).

What led to the publication of this valuable account in a Cairo journal was the desire to refute the accusation published previously in an earlier issue of the journal that Abdullah Quilliam and the small community of Liverpool Muslims was seen as the modern-day equivalent of “fake news”, designed to promote Britain’s imperial interests in Egypt and elsewhere among its Muslim subjects. The editor of the journal had himself been part of the Egyptian anti-colonial struggle against the British, and so in order to explain why there would be so much suspicion of the authenticity of a small, British Muslim community of converts, it is necessary to say more about this struggle first of all, before presenting the eyewitness account itself.

The ruler or Khedive of Egypt, Ismail I, who reigned 1863-1879, borrowed an immense amount of money from Britain and France to fund schools, factories, railways and the huge Abideen Palace. Years later, in 1869, the Suez Canal opened with Ismail I’s enormous steam-powered yacht, El Mahrousa, sailing through it. But this show of national pride came at a price: Ismail I borrowed so much money that, by 1875, Egypt became bankrupt because it could not repay its debts. Compounding Egypt’s woes was that, being under the suzerainty of the Ottomans, she had to pay her taxes to them. Naturally, with this double burden, local taxation went over the roof, causing strive and division among the Egyptian people.

Ismail I pondered possible solutions and his was to invite Britain and France to administer his finances. They sucked dry the labours of the common people. Jamal al-Din al-Afghani lamented, “Oh, you poor peasant (fellah)! You break the heart of the earth in order to draw sustenance from it and support your family. Why do you not break the heart of your oppressor? Why do you not break the heart of those who eat the fruit of your labour?” [1]. What had been a source of national pride, the Khedive’s investments, was slowly costing blood and life of the nation, and the resulting unrest imperilled his position.

Pressured by his own government to end the heavy British-French taxation from milking the Egyptian economy dry, Ismail I reneged on his promise to repay the debt. Ismail I was succeeded by his son, Tawfeeq Pasha, who reigned 1879-1892, and who did not oppose continued British-French taxation. He also promoted non-Egyptians in the army while retiring Egyptians due to the lack of funds in the coffer. This discrimination – along with other problems – had begun under Ismail I but had spun out of control under Tawfeeq Pasha.

It was in this context that Ahmad Urabi came of age. A farmer’s son with little education, he joined the army. He went up the ranks but hit a glass ceiling like his fellow Egyptians, while foreigners like Turks and Circassians got promoted. Urabi was angered by foreign dominance of the nation’s finances and the army’s higher ranks.

Urabi and his supporters, many from peasant backgrounds, saw this as a flagrant insult to the nation’s pride – so they protested against the government. A civil war nearly broke out but was avoided at the last minute. Urabi’s nationalistic slogan said in front of Tawfeeq was never forgotten: “Egypt for the Egyptians!” Urabi gained in popularity and became head of an advisory council to guide Tawfeeq on decentralizing foreign power. However, both Urabi and Tawfeeq wanted to depose each other, the latter having the support of the British and the French. War between the two loomed.

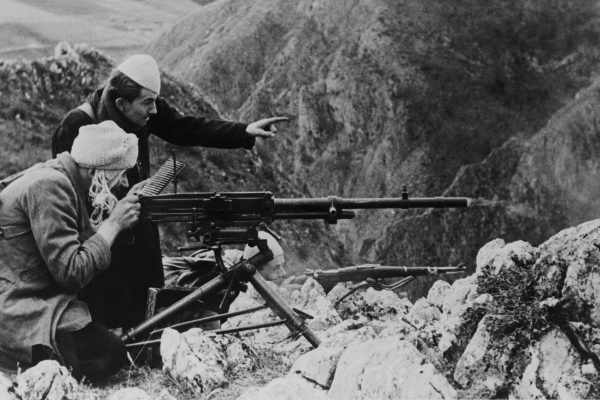

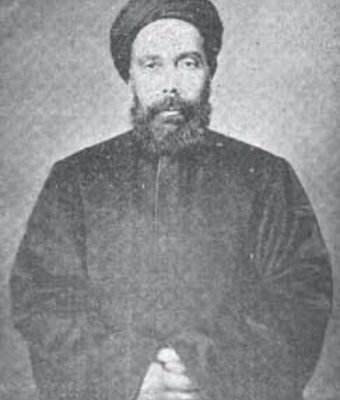

Fearing that Urabi would end their influence in Egypt, the British docked their warships in Alexandria, which led to a riot that was planned by the Khedive, on the streets and the beginning of the Anglo-Egyptian war of 1882. The British bombarded the city for hours, who had Tawfeeq’s support. Urabi led an army of Sudanese and Egyptians against the Khedive and his British backers. After two months of fighting, Urabi lost the Battle of El Kebir, surrendered, and was sentenced to death, later commuted to exile in Sri Lanka. Some of Urabi’s other supporters were exiled such as the popular Abdullah al-Nadim al-Idrisi, who had openly advocated for the Urabi revolt [2]. He managed to evade exile for a few years but was caught and sent to Jaffa, Palestine. Al-Idrisi was later allowed to return to Cairo and during his short stay there, he founded the journal, Al-Ustadh.

It was in this journal that the Liverpool mosque of Abdullah Quilliam was slandered as a “political mosque”. The author of those slanderous words was anonymous, but the writer clearly was an anti-colonialist. “It is better for you to chop your hand off than to place it in the hand of the foreigner [i.e. the British]” because the British “win you over with false promises and flimsy tricks”. Then he mentions, “That political mosque located in Liverpool, the one built and made popular by the colonialists of Egypt, to deceive the Egyptians with it, hearing of the Islam of [converted] British in their own country….They spout lies that they make up for Islamic newspapers and insert idioms never used by Egyptians, that were never on their lips….” [3].

This was a strong accusation but rebuttals from two other Arab correspondents were published quickly in Al-Ustadh; one a week later from Mahmoud S.; another by an anonymous Egyptian, presumably “A.H.”, a month after that, whose eyewitness account I present below. Mahmoud S. respectfully disagrees with the slanderer. He writes, “I know that the one who built the mosque established it with an honest motive [which was done] by our brother Abdullah Quilliam and his brothers [i.e. the other Muslim converts] and our proof is his incisive, resounding books…[offering strong] proof for the soundness of the Islamic religion….” Other praiseworthy matters are discussed such as Quilliam’s influence reaching America and people converting to Islam in groups due to him [4].

This second account below is based on the personal experience of the anonymous Egyptian writer, “A.H.”, when he met Quilliam in Manchester [5].

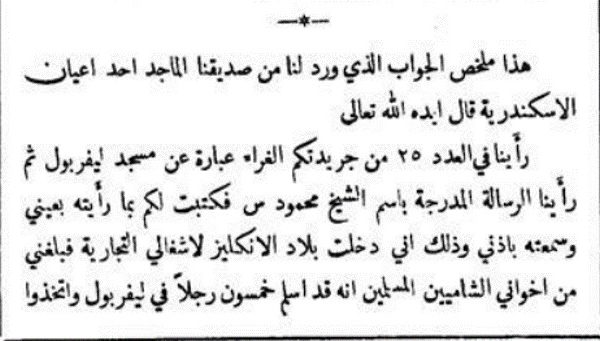

al-Ustadh

4 April 1893

Issue 33

Pages: 766-768

This is a brief answer that arrived from our great friend, one of the notables of Alexandria. He said, may Allah Almighty support him,

We saw in the 25th issue of your journal, curiosity about the Liverpool Mosque. Then we saw a letter by Mahmoud S., [which prompted me] to write to you about what I saw with my own eyes and what I heard with my own ears. I entered the land of the British for trade and one of my Levantine [6] Muslim brothers informed me that he [Quilliam] had converted fifty people to Islam in Liverpool and that they built a mosque for the purpose of salah. Thereupon I took one of my brothers and went from Manchester to Liverpool and we saw the mosque, which is an old building, written upon it [on a sign] “House Musulman”. We knocked on the door and a servant answered and allowed us in.

In front of the house [corridor] there was a board [written] upon it “La ilaha illa Allah Muhammadur Rasool Allah” and they made for it [the mosque] a qibla which I checked with my compass and found out it was accurate. We then asked for Abdullah Quilliam and we were told he would come at sunset, so we left for him [Quilliam] an invitation card and headed back to Manchester. The servant gave us small tracts, written for the purpose of making people interested in Islam.

Then a book came to us from Quilliam, thanking us for our efforts and wishing to meet us. We informed him of our readiness to do so. He arrived in Manchester and we, along with the Levantine Muslims, met him at the [train] station. We headed towards one of the brothers’ house. Accompanying him, from among the women who converted, was a woman called Fatimah [most likely Fatimah Cates]. After we ate, he [Quilliam] told us his [conversion] story and the arduousness of converting fifty people and that he was married to one of those Muslims in accordance with the Sharia.

Every Friday and Sunday he preaches to them and shows them the correct [way of life]. All of the money spent on the mosque is from his own pocket and that his cause of conversion was due to being a traveller in Gibraltar where he came upon a group of Hajjis on a steamer whereupon he questioned them about their faith and they told him about it. He [later] looked for books on Islam but learned a few surahs of the Qur’an and Islamic theology at the hands of the Hajjis. Then the [Levantine] Muslims were motivated to open a mosque in Manchester. They volunteered immediately and so did I in order to find a suitable spot and they resolved to establish it. We then yearned to see and pray in the Liverpool mosque.

So I headed with a group of [Levantine] Muslim brothers [to the mosque] and when the time [of prayer] began, on the balcony of the house [mosque] an Indian student made the call to prayer in Arabic, followed by a British man who made the call to prayer in English. Many people gathered to listen to the speech and after it Quilliam said, “Now the prayer will begin. Whosoever is a Muslim should remain. Whosoever else wishes to leave should leave.” The Maghrib prayer was prayed in congregation and the president [Quilliam] informed us that he planned to open a special place for women. He sent a letter to Indian notables, requesting them to send him a [female] teacher who knows English. He also planned to purchase a printing press for the purpose of publishing religious books and newspapers [The Crescent and The Islamic World]. We then bade him farewell and left towards Manchester. Days later, the newspaper he published arrived.

I wrote this for you containing the truth of the matter [of what I saw], leaving what is concealed [i.e. the intention of British Muslims] to Almighty Allah. There is no duty on us to judge others except by what is apparent. Allah knows best the truth of concealed matters [7].

– A. H.

The Urabi Revolt was defeated, Britain took sole control, excluding French interests, and Urabi was exiled. Despite this, his influence would remain and his nationalistic fervour would survive in the decades to come in one form or the other. This influence was not only found in Egypt but also in a private letter Abdullah Quilliam had received. In June 1893, Quilliam published this letter from an Egyptian who was “discontent[ed]” with British colonial rule in his homeland:

“In Egypt everyone but an Egyptian has a finger in the governmental pie. […] England must learn our national aspirations; except the Radicals, [8] none of your fellow countrymen understands in the slightest degree either our true position or even the interests of Great Britain herself, where the Nile-Valley is concerned. The only keepers of the British conscience, the only ones who have Britain’s ear on the question of Egypt, are the only class interested in the occupation—the rich financiers. The British press voices solely the aspirations of the [bankers] Goschens and Fruhlings. Thus truth wanes, and international justice becomes a nullity.” [9]

The idea that everyone but the Egyptians has a “finger” in the governmental “pie” owed its most powerful and recent expression in the uprising led by Ahmed Urabi. This belief would remain and later be popularised by a later president of Egypt, Gamal Abdul-Nasser, who would exonerate Urabi after he had been traduced by previous governments.

Concerning Mahmoud S., author of the second article published in Al-Ustadh, he may well be Mahmoud Salem who had contact with Abdullah Quilliam prior to the publication of The Crescent. In February 1893, Quilliam received a letter from “Mahmoud Salem, Judge of the Mixed Tribunals, [city of] Mansoura, Egypt”. The letter provides insight into how Quilliam, in his early years, already established connections to the outside world. Salem wrote:

“Therefore, we beg of you very kindly to keep us posted in the progress made by your sympathetic community and to send us, if possible, every pamphlet or other publication conducive to informing us and at the same time tranquillizing our spirits: for these last days have brought us rumours of an attack upon you Liverpool Mussulmans by a section of the ignorant populace. This attack and maltreatment can but awaken afresh our sincere friendship toward you all. Should you have a journal specially treating of your Institute, kindly inform me, and I shall subscribe to it, so as to be in a better position to reassure the minds of our coreligionists in the East. Personally, I am entirely at your service, supposing I can be of any use to you in anything whatever I shall be positively delighted, and beg of you to rely on my devoted disposition to serve you. Accept, Sir, my most marked compliments, together with my sincere respects for all your confrères.” [10]

It can be assumed that Quilliam and Salem’s friendship blossomed.

In 1895, a British convert Hajji Abdullah Browne, another friend of Quilliam’s, would meet “Mahmoud Salem Bey” in Alexandria and became his guest for some time, where Browne edited the Egyptian Herald, which advocated “the administrative autonomy of Egypt and the interests of Islam throughout the world”, and was financed by the Ottomans [11]. One can speculate as to whether the descendants of Mahmoud Salem have preserved any correspondence from British converts to Islam up to present day.

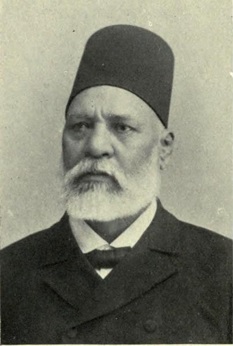

The dispute over the authenticity of the Liverpool Muslims and their leader Quilliam came to the attention of the noted scholar and revivalist, Sheikh Rashid Rida (1865-1935). Rida was sufficiently curious to seek clarification on the matter from his teacher, Sheikh Muhammad Abduh (1849-1905), the famous Egyptian scholar and reformer, later to be appointed Grand Mufti of Egypt, who was himself exiled for six years by the British for supporting the Urabi Revolt. Rida asked if the Islam in Liverpool “is a correct Islam or political?” Abdu replied that it was real, which surprised Rida, because “political intrigue does not come from the general public, and they [the British Muslims] are part of the general public.” [12]

Perhaps in pursuit to discover whether Quilliam’s conversion was honest, Rida read & reviewed Quilliam’s second book, The Faith of Islam [13]. Rida “considered [it better than] any other classical theological work” because it explained the fundamentals of Islam in a “modest way”. However, despite the favourable review, Rida was also critical regarding some points raised by Quilliam [14].

Conclusion

The eyewitness report translated fully above sheds light into the scepticism of Muslims, especially from Egypt due to the recent defeat in El-Kebir in 1882 and the subsequent colonisation by the British. It also confirms that the Manchester mosque, if it was ever set up by the Levantine Arabs in the city in the early 1890s [15], was directly inspired by the example of Abdullah Quilliam and the Liverpool Muslim Institute [16].

References and Notes

* Originally published on my Academia page.

This was heavily edited by Yahya Birt, for which I’m grateful!

1) de Bellaigue, C. 2018. The Islamic Enlightenment: The Modern Struggle Between Faith and Reason. Vintage. P. 208.

2) For the exile of al-Idrisi and the general history of the Urabi Revolt, see Reid, D. M. 1998. The ‘Urabi revolution and the British conquest, 1897-1882. In The Cambridge History of Egypt. Vol 2. Chapter 9; Hussain, M. S. 2015. British Policy and the Nationalist Movement in Egypt, 1914-1924: A Political Study. Klaus Schwarz Verlag. Pp. 14-28.

3) Anonymous. 1893. Hathihi yadi fi yad man ada’ha. al-Ustadh. Issue: 29. Pp. 695-699.

4) S. Mahmoud. 1893. Masjid Liverbool. Al-Ustadh. Issue: 30. Pp. 721-722. Mahmoud S is also the author of Les Voyageurs Musulmans in which he discusses Muslim voyages of the past.

5) Anonymous. 1893. [Untitled]. al-Ustadh. Issue: 30. Pp. 766-768. Anything in between square brackets are my input for the sake of ease of reading.

6) Or could be translated as “Damascene”. Shami can refer either to the region of the Levant or to the city of Damascus. See Musalha, Nur. 2018. Palestine: A Four Thousand Year History. Zed Books. Pp. 6-7.

7) According to the Liverpool Mercury, it records that “…a number of influential Moslems from India, Syria, Egypt and Turkey…” arrived at the Liverpool Mosque. The newspaper carries on providing names of who did the athan, who led the salah and even the name of lecture done by Quilliam, entitle “God’s witnesses”. However, the details in the newspaper contradicts the eyewitness account in al-Ustadh. Perhaps both are referring to the same event with contradictory statements or two events took place with large number of Muslims attending. The newspaper is dated prior to 1893, which was before Quilliam purchased a printing press and therefore consistent with the eyewitness account. See Liverpool Mercury, 9/8/1892, p. 6.

8) A British parliamentary faction. See Wilson, A. N. 2003. The Victorians. Arrow Books.

9) The Crescent. Vol 1. No. 21. 10/6/1893. Pp. 167-168.

10) The Crescent. Vol 1. No. 3. 4/2/1893. Pp. 21-22.

11) Abd-Allah, U. F. 2006. A Muslim in Victorian America: The Life of Alexander Russell Webb. Oxford University Press. p. 75; Wood, H. F., 1896. Egypt under the British. London, Chapman & Hall. Pp. 122-123.

12) al-Adawi, I. A. [Undated]. Rashid Rida: al-Imam al-Mujahid. P. 96.

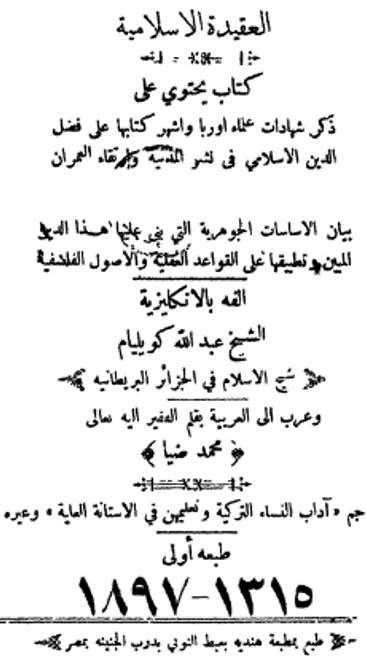

13) Quilliam, W. H. 1892. The Faith of Islam. Liverpool, UK: Willmer Brothers & Company, Ltd. The Arabic edition was translated by Muhammad Diya’ in 1897 as Al-‘aqida al-Islamiyya.

14) Ryad, U. 2010. Islamic reformism and Great Britain: Rashid Rida’s image as reflected in the journal Al-Manar in Cairo. Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations. 21(3): 263-285. (276-277).

15) A steady flow of Muslim Syrians did travel to the UK, especially Manchester, as shown by Mohammed Seddon in his talk at MACFEST 2020 entitled “History of Muslim Settlement in Manchester”.

16) On the Liverpool Muslim Institute, which was set up by Abdullah Quilliam, see Geaves, R. 2013. Islam in Victorian Britain: The Life and Times of Abdullah Quilliam. Kube Publishing. Chapters 3 and 4.