What was 11th century Baghdad really like?

What was 11th century Baghdad really like?

To the students of Islamic Studies, especially the students of Hadith, the name Al-Khatib Al-Baghdadi (d. 1071 AD) holds a particular grandeur that depicted not only a glimpse of the golden age of hadith studies, but also the high-culture living synonymous with the 11th century Baghdad.

Author of the legendary Tārīkh Baghdād [1] or also known as Tārīkh Madinatus Salām (Madinatus Salam or the City of Peace was Baghdād’s nickname during its heyday), whose other works included Syaraf Aṣhābil Hadīth (The Honour of the People of Hadith), Al-Jāmi’ li Akhlāq ar-Rāwi wa Ādāb as-Sāmi’ (A Compilation on the Manners of Teachers and Etiquettes of Students), ar-Rihla fi Talab al-Hadith (Travels in Search for Hadith), and al-Kifāyah fi ‘Ilm ar-Riwāyah (The Complete Guide to the Science of Riwāyah) among others, carried the banner of the intellectual tradition uniquely Islamic; the Hadith tradition.

Nevertheless, as orthodox as that sounds, one can also find accusations of Al-Khatib subscribing to the sect Mu’tazilah, which has rendered him to some, as being quite problematic and not a ‘pure’ Sunni, but that is another discussion unfit for this place.

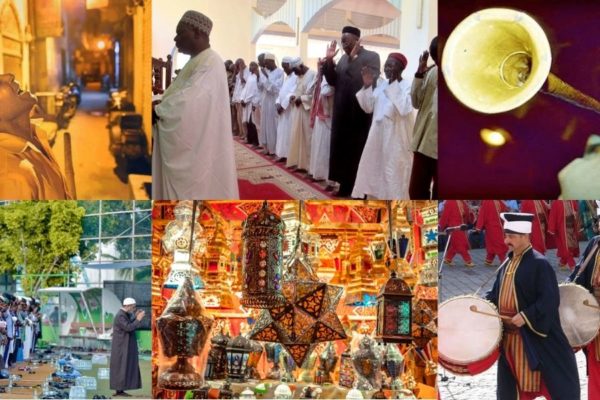

Now, panning our view to the historical background, the medieval Baghdad from where stories like Shahrazad’s 1001 Nights came from needs to be pictured as hosting the most unorthodox events; parties and celebrations, singing and dancing, poetry reading and oud playing ceremonies littered the houses especially the rich merchants and artists whose prose echoed on the tongues of every man and woman. At the same time, it needs also to be pictured as hosting highly prestigious religious universities and learning centres where students of knowledge from all over the world congregate to learn the religion from the master scholars, while scholarly events such as Hadith readings/narrations (majālis riwāyat al-hadīth) were conducted in large scales.

That was the time when giants such as Abu Nu’aym Al-Isfahāni (d. 1038 A.D), Abu Ishaq Al-Syirāzi (d. 1083 A.D) (both were his teachers) and many others were alive. As such, there emerges a unique picture of medieval Baghdad, the epicenter of Islam, which was colored by many interesting shades, far from being the monotonous picture that certain readings try to paint – either extremely ‘liberal’ or extremely ‘conservative’.

As such, it is not a surprise when a giant Hadith scholar such as al-Khatib himself had an ‘unorthodox’ [2] side in which he espoused it through a collection of funny stories or anecdotes, a satire of some sort, to a ‘viral’ trend that seemed to be rampant during his days; party crashing (at-taṭfīl). The treatise that was originally named as al-Tatfil wa Hikayat al-Tufayliyin wa Akhbaruhum wa Nawadir Kalamihim wa Ash‘aruhum (Early Party-Crashing: Mention of the Party-Crashers’ Conversations, Advice, and Poetry,) has then been simplified and translated into English by Emily Selove, by the name of The Art of Party Crashing in Medieval Iraq.

Reading the treatise, one cannot help but be amused by the sense of humour and light-heartedness shown by al-Khatib, different from his heavyweight books on religious matters, and also by the way he wrote the book – it was written in a classic hadith style; each anecdote bores a full chain of transmission (sanad) with little to no commentaries by him, which is unfounded and unthinkable of in this day and age, when picturing a joke book. It was, so to say, a matn [3] of stories on party-crashers!

As arduous as one may find all the chain of transmissions might be, it is actually an important piece of information, so as to understand the context of the stories, and among whom these stories circulated. This then i.e., the sanad, is among the novelties of the Islamic civilization absent among others.

Of the chapters that can be found in Selove’s edition are “The Meaning of Party-Crashing in the Language and the first person named after it”, “Early Party-Crashing”, “Going to a Meal Without Being Invited is Deemed Rude”, “Those Who Cast Aspersions on party Crashing and Its Practitioners and Satirize and Denounce Them”, “Those Who Praise, Make Excuses for, or Speak Well of Party-Crashing”, “Party Crashers from Among the Notables, the Noble, the Learned, and the Cultured” and others.

Through the narrated anecdotes, a flavour of free-spiritedness can be seen weaving through the fabric of the Baghdadites, especially among the artists and the royals with all their drinking and music, but the most interesting occurrence is the usage/reference of Quranic texts in their wordplay (iqtibās), which apparently has been criticised by some scholars and has been a subject of discussion among the later researchers. Nevertheless, it still shows the high sense of familiarity with the Quranic text, and the reverence that they held to the Quran, and that instances of jest have never been the case.

However, according to Selove, the book represents more than just anecdotal narrations – it is a social commentary and a reflection of the Baghdadian concerns during the time, ranging from trivial issues of mannerisms to bloody (literally) politico-theological scandals, where the heavier themes can only be found through a thorough excavation across his other works. In this manner, Selove again identified a few underlying messages that can be deduced from this interesting work [4].

Of them is on the issue of hospitality and miserliness, where we can see that these party-crashers, albeit annoying, were the protagonists in his view, as opposed to those who denied these party-crashers, whom he saw as the misers (al-bukhalā’) [5]. Apart from that, al-Khatib was also discreetly addressing another bigger issue that was hanging around the seminaries and castles of Baghdad – knowledge gatekeeping by the governments.

During his time, the Islamic intellectual scene was experiencing a scandalous event, one that will later, according to some scholars, become the litmus test to identify the Sunnis from the non-Sunnis – the miḥna of the createdness of the Qur’an. It was during this timeline that the torture of Imam Ahmad (d. 855 A.D) happened, and many others were executed. Scholars were taken for questionings, and many didn’t come back. The government, at the time, had taken the theological stand of the Mu’tazilites, that the Quran was a created being, as a political agenda thus those who opposed the idea would be executed [6].

This, according to al-Khatib, was a form of knowledge gatekeeping as ‘the people of knowledge’ then was determined by the authorities, resulting in an elitist bifurcation of intellectual activities. Allusions to this issue are present in his stories of party-crashers where he, for example, narrated an incident that depicted a man who had wrongly crashed what he thought was a party, but instead it was an execution ceremony by the Khalifah [7].

Another underlying message insinuated by al-Khatib in his book touches a deeper side of man himself; that man’s relationship with the Unknown is inseparable, thus a constant humility is needed for the Knowledge behind the veil of the Unknown, which is God’s and to whom He has bestowed a dint of it, is of unimaginable vastness. Of this, al-Khatib alludes to it in the stories of Bunān, a trickster who memorizes only a part of an āyat from the Quran [8]; “Give us our lunch!” (ātinā ghadā’anā!) [9], of which, when referred to the context of the āyat, can be understood as a symbolism that alludes to the meeting point between two types of knowledge; the apparent and the hidden – esoteric and exoteric knowledge [10].

To conclude, there is a hadith that mentions Paradise as a party (ma’dabah) hosted by God [11]. He invites people through His messenger, and whoever answers the invitation will be graced by the Host while whoever doesn’t, receive His displeasure. Knowing that the Host is the Most Generous, it is not far-fetched to liken ourselves to party-crashers who, knowing the we will never be rejected, will go running to His party with hungry hearts carried in bags made of hope, like what has been said by Ḥāfeẓ (d. 1390 A.D) the Persian mystic-poet: “everyone is a party-crasher of the Existence of Love”.

[1] It is a 23-volume compendium of the history of Baghdad, compiled in the manner of a biographical database synonymous with the works of hadith scholars. [2] I used the word unorthodox in the sense that he came out as someone that was ‘into-the-scene’ of the current issues, and eccentric in some sense. Maybe in this modern day he would be seen as someone ‘relatable’. [3] Matn literally means text, and it is generally used in the Islamic literature to denote an original text of an author without any commentaries, usually from a different author, as commentaries or sharḥ usually accompany original texts. For example, the text of the 40 Hadith of Imam al-Nawawi is call matn, while any commentaries on the matn is called Sharḥ. [4] Emily Selove, Heretics and Party-crashers: Al-Khāṭīb al-Baghdādī’s Kitāb al-Taṭfīl. [5] He has a separate book on them. [6] For a detailed information, look into history books :D As an introduction, see: https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/display/document/obo-9780195390155/obo-9780195390155-0205.xml [7] Al-Khatib al-Baghdadi, Taṭfīl, anecdote 93. [8] Al-Khatib, Tatfil, anecdote 179. [9] Al-Kahfi: 62. [10] Emily Selove, Heretics and Party-crashers: Al-Khāṭīb al-Baghdādī’s Kitāb al-Taṭfīl. [11] Sunan al-Darimi, hadith no: 11, its chain is weak, but the meaning is sound.

Bibliography

Emily Selove, ‘Heretics and Party-crashers: Al-Khāṭīb al-Baghdādī’s Kitāb al-Taṭfīl’. Journal of Abbasid Studies 6, (2019): 106-122