“I turned out to be an atlas of the world, a cartographic fusion of East and West.”

“I turned out to be an atlas of the world, a cartographic fusion of East and West.”

“A palm tree stands in the middle of Rusafa,

Born in the West, far from the land of palms.

I said to it: How like me you are, far away and in exile,

In long separation from family and friends.

You have sprung up from soil in which you are a stranger;

And I, like you, am far from home.”

– Ode to the Palm Tree, by Abdulrahman Al-Ummayad

A few weeks ago, I received the results of my DNA test and it was amazing to discover how many genetic surprises a small vial of saliva could yield. The ethnicity estimate provided by the test is derived from continental regions and lays out a map of where your ancestors came from. The continental regions are further broken down into trace regions that add to an understanding of the arrangement of your genetic pieces, each region acting as a mountain or knoll corresponding to genetic percentages contained, like a topographical relief.

I turned out to be an atlas of the world, a cartographic fusion of East and West, the new and old worlds, Muslim, Jew, Christian and pagan-crusader, believer and infidel.

As I looked over my trace regions one stuck out – 6% Syrian/Iraqi. A small percent, a genetic knoll linked me to a region currently in turmoil and hemorrhaging people. It was a significant personal find since I spent the last five years advocating for Syrians. Yet, what was of more interest to me was how that Syrian DNA got there. I am of Mexican decent so my family roots are partially Spanish, which made it no far leap to understand where the Syrian/Iraqi came from. Spain’s history and people were influenced by over 800 years of Arab/Muslim culture, but I was looking for a deeper historic understanding. I found it in a book sitting on my shelf, The Ornament of the World by Maria Rosa Menoca and from this I began to piece things.

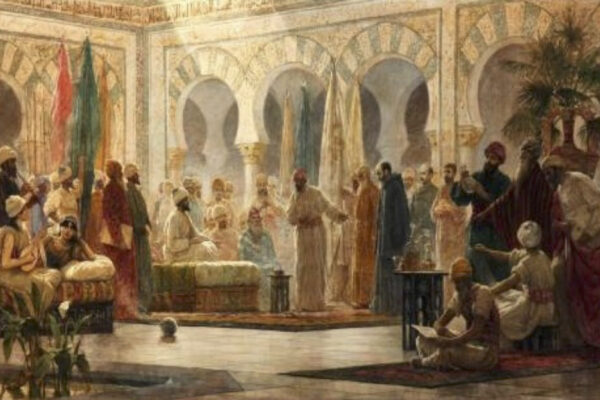

On September 755, Abdulrahman, the last of the Umayyad’s, fled his home in Damascus, Syria to escape the same fate as his family, all of whom were massacred. He was the last in his line, a Noah’s ark of a dying civilization. His Aeneas-like departure took him to Egypt and then Morocco following his earlier Syrian predecessor, Tariq ibn Ziyaad, who in 711 was the first Syrian to cross the Mediterranean into Spain.

Centuries later, thousands of Abdulrahman’s countrymen and women would follow him on little, inflatable boats into European exile.

Abdulrahman, a fusion of Syrian and other cultures, was the quintessential Umayyad, and like other nostalgic refugees, he set out to recreate what his family lost in Damascus. However, unlike other refugees, Abdulrahman had the resources of a prince at his disposal to enable him accomplish this on a grand scale.

He did so in the Umayyad tradition by integrating and assimilating into local culture to produce something new and unique in Cordoba, Spain. He built the Palace of Rusafa as a memorial and homage to his family home that he left behind on the steps of North-Eastern Damascus. It was in that memory palace that he wrote his Ode to a Palm Tree, part autobiography, and part homage to his birth country. His garden became his refuge in his old age and he had built what he lost. He wanted to recreate what he lost and in the process, he set the foundation of modern Europe.

Abdulrahman ushered in a golden age in Medieval Europe that was midwife to the Renaissance and laid the foundation for European Imperialism. A cash-flushed Isabel I and Ferdinand II fresh from the conquest of Granada on January 3 1492, agreed to fund Columbus’ voyage and later that year, he set sail from Granada, paving the way for European empire building in the centuries to come.

Abdulrahman ushered in a golden age in Medieval Europe that was midwife to the Renaissance and laid the foundation for European Imperialism. A cash-flushed Isabel I and Ferdinand II fresh from the conquest of Granada on January 3 1492, agreed to fund Columbus’ voyage and later that year, he set sail from Granada, paving the way for European empire building in the centuries to come.

The civilization Abdulrahman began was the nexus between multiple civilizations and was the inception of a new Western identity influencing every aspect of life; from the way stories are told to how universities and hospital wards are run. Abdulrahman had something valuable to give Europe and the newly arrived refugees also have something to offer.

Today’s European social democracies require a tax base of able-bodied workers to maintain their high standard of living. As Europe’s population atrophies and the tax base shrinks, the refugees can help invigorate the economies of their new countries, and provide diversity of thought that if often the engine of innovation.

This new wave of Syrian refugees does not need to be a clash of civilizations. It is a homecoming to a system their ancestors helped put in place. We are a mix of DNA, particularly Europeans who experienced waves of immigration over millennia. It is this variety that contributed to the make-up of the Western world. Humanity, swarming around the globe, always searching and always home, this is the story our DNA tells us.

We are the story we accept, the version of our past that most resonates with our present. Perhaps I am one of Abdulrahman’s descendants; maybe we all are Andalusians, a beautiful mix of humanity.