The oppressed must rise up to breathe. They simply cannot conceive of life without the air of liberation.

The oppressed must rise up to breathe. They simply cannot conceive of life without the air of liberation.

Black Lives Matter is a distinct phenomenon. It at once represents the exceptional struggle of a historically disenfranchised people; yet stands upon the same principles that Muslims today identify with.

But now is not the time for Muslims to footnote #BlackLivesMatter with our own decontextualized political grievances. Neither is it opportune to futilely champion anti-racism in an Islamic tradition which progresses way past reactionary preaching.

Now is the time for reflection and education. To learn from this movement in mobilising grassroots activists; to build coalitions of interest groups with real synergy; to seek the roots of systemic oppression and trace its infestation in Muslim communities.

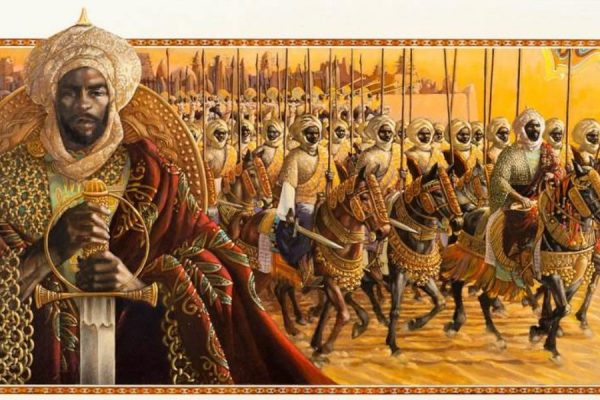

This initial reflection is painfully deconstructive of contemporary Muslim identity. We must root out, from our own descriptions and speech, Western projections of who we have been told we are. Serving the community starts with recognising your true value.

Using Fanon

The works of decolonial theorist Franz Fanon are valuable tools in the hands of enlightened activists. His is the perspective of an Algerian psychoanalyst observing how systemic colonial oppression begins with distorted conceptions of the self.

Slavery begins not at the plantation, but in the slave’s acceptance that he is enslaved, according to Fanon. The dialectic mastery of the coloniser is now infused in his own mirrored reflection; the black person today is riddled with insecurities about self-worth, his own moral impurity, and political insignificance.

Fanon wanted to expose the fingers of the coloniser in crafting ‘the black soul.’ “We observe”, Fanon writes in Black Skin White Masks, “the desperate struggles of a Negro who is driven to discover the meaning of black identity. White civilization and European culture have forced an existential deviation on the Negro … what is often called the black soul is a white man’s artifact (page 16)”.

Fanon clinically reviewed the underlying assumptions of his patients to describe this process of internalising oppression.

Some patients dreamt themselves as invisible, believing and reflecting their own worthlessness as projected on them by employers. Black children dreamt themselves rosy-cheeked and white, often running away from dark shadowy figures – their infantile notions of safety and harm compromised by colonialism.

Black people often perceived one another with characteristics of savage cannibals – replicating the same objectification cast upon them. They could never be the subject of their own story.

Our Struggle

The only hope is revolt. Fanon deftly navigates through literary and psychological instances of internalised and manifest oppression, using theory when needed, to reach the destination of emancipation.

The colonised black person must rise up “quite simply because he cannot conceive of life otherwise than in the form of a battle against exploitation” (Black Skin White Masks, page 223). These violent means must entail violent ends, he argued, in order to fully dis-alienate from the coloniser’s exploitation and collectively rebuild an authentic humanity as a community. Only when one is free from psychological subjugation can they attain self-realisation.

This is precisely the task Muslims face now. We too must root out the coloniser’s interests from our social systems. The true causes of our political woes have remained undiagnosed for too long.

The Euro-centric imperialism which targeted Fanon in North Africa is the same source of malaise in Muslim-dominated Middle Eastern, African, and sub-continent Asian nations. Even in our religious practice – what we accept and discard as relevant in today’s society – is often in service of liberalist and capitalist interests that we would never know had mastery over us. Dr. Rebecca Masterton adds:

“Muslim countries have been subjected to methods of psychological and spiritual subjugation, control, and remoulding that are continuing today. Colonialism is not a thing of the past: it has just morphed into something more subtle, so that Muslims today can’t even see the extent to which they are enslaved.”

It’s subtle. It’s in the haste by which we discard seemingly parochial interpretations of the Qur’an. It’s in the embarrassment of putting on a headscarf when nobody else does. It’s in oscillating skin tone and accents and speech. It’s in walking through museums comprised of artifacts that had spiritual value in the mosques of old. It’s in conceding that you are Western first, Muslim second.

#BlackLivesMatter

If it’s true that colonialism has simply a morphed form today, we now see Black Lives Matter with clearer vision. Minneapolis protesters are described as violent because the colonial narrative requires them to be. When you dehumanise a person, they lack the humanity to deserve air to breathe.

Sayed Hadi Rizvi, quoting Fanon in Wretched of the Earth, shows us how to use Fanon’s work in rationalising current events: “When we revolt it’s not for a particular culture. We revolt simply because, for many reasons, we can no longer breathe (Wretched of the Earth, page 65)”.

Sayed Hadi contextualises the quote in America today:

“Now in the process of naturally being coined as the chant of the justice-seeking marginalised populations of the US, and the cry that unites them as an oppressed group in their country (‘I can’t breathe’), the phenomenon of Combat Breathing was touched upon by Fanon in his works.”

The oppressed must rise up to breathe. They simply cannot conceive of life without the air of liberation. We must know precisely the symptoms of our suffocation in order to develop projects that alleviate each instance of oppression. This helps to understand other struggles, and our role in them, as well as developing frameworks for our historical struggles.

Sayed Hadi adds: “Fanon also spoke about the different intensities in the response of the subjugated people towards their oppressors. His books are an essential part of any decolonisation reading list.”

And so, in our solidarity, let us read and reflect.

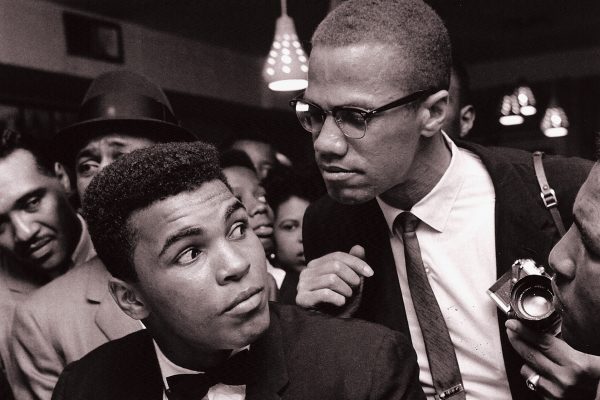

We must be better equipped to detect the resistance within Ali’s shuffling, Simone’s contralto, Baldwin’s soliloquies, and Malcolm’s oratory. Muslims must go deeper still. And to go deeper is to reach Fanon.