While it is true that Black American Muslims were often drawn to Islam in an attempt to articulate their own cultural identity outside of the dehumanizing ascribed identity of Black inferiority, Black American Islam is thoroughly embedded in the American tradition.

While it is true that Black American Muslims were often drawn to Islam in an attempt to articulate their own cultural identity outside of the dehumanizing ascribed identity of Black inferiority, Black American Islam is thoroughly embedded in the American tradition.

The Muslim American community is held together with the belief that there is no God but the One True God and that Muhammad is His prophet. Muslims share daily patterns of worship, rituals of birth, marriage, and death.

As one of the most diverse faith communities, Muslim Americans come from various ethnic, socio-economic, and cultural backgrounds. Sometimes there are various articulations of Islam due to different political, cultural, and religious orientations.

Some estimates go as far to say that there are 5 million Muslims in America. According to census data and information provided by mosques and community centers, Muslims in America make up .5% of the total population in America. Keeping it conservative, that equals just under two million. This still represents a significant number. CAIR reports that the ethnicities of mosque participants can be broken down to 33% South Asian, 30% Black American and 25% Arab, 3.4% sub-Saharan African, 2.1 European (i.e. Bosnia) 1.6% White American, 1.3% South-East Asian, 1.2% Caribbean, 1.1% Turkish, .7% Iranian, and .6% Latino/Hispanic. Other reports indicate the number of Black Americans may be even larger.

Regardless of the numbers, there is no clear ethnic majority in American Islam. But these numbers raise some important issues: Who has the right to speak for American Muslims? Who are the real Muslims? Who will define the agenda for American Muslims? These questions have often been central to a debate that has emerged about the Black American/immigrant divide.

Over the years, many Black American Muslims have been at the forefront of articulating Islamic thought for the growing American Muslim community. But this seems to have changed as a dominant narrative has taken over.

Black American Muslims and Islamic Thought in the United States

In America, there is fierce competition over resources which has led to some voices getting silenced in deciding the agenda for American Muslims. Within mainstream media, the Muslim American experience is about the immigration and assimilation experience. There is little press coverage or interest shown in the media on converts or the multi-generational Black American Muslim families.

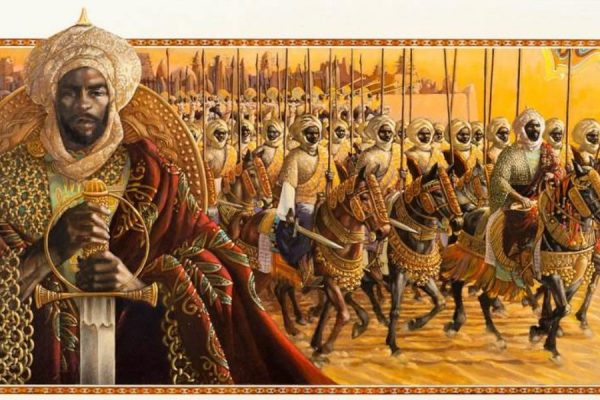

Sylvia Chan-Malik uses the term, “foundational blackness” to describe how contemporary Islam in America can best be understood by transnational affiliations that link gender, class, and religion, but also with its relationship with blackness. However, Black American Muslim foundations go back further, with memories of African Muslims enslaved in the Americas, even predating the formation of the United States.

There are also Sunni communities dating back to the 60s, such as Dar al-Islam movement. Some communities have origins much earlier, such as Quba Institute with roots in the 1930s Izideen village in New Jersey. Yet, consistently, there continues to be a portrayal of Islam as a foreign religion, with only internationalist interests. For over a century, some Black Americans have looked to African cultural legacies, addressed local issues, and have maintained transnational networks and ties, to articulate religious thought that is African, Islamic, and uniquely American.

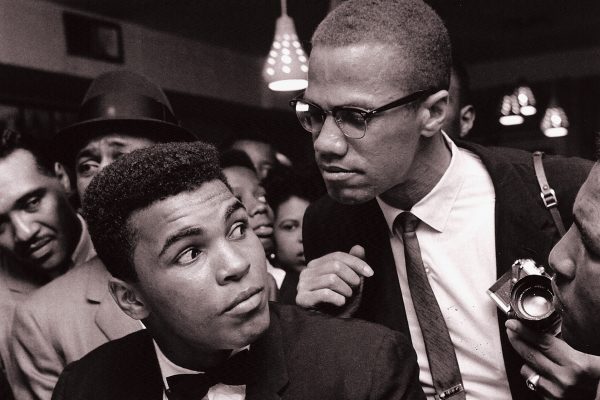

While it is true that Black American Muslims were often drawn to Islam in an attempt to articulate their own cultural identity outside of the dehumanizing ascribed identity of Black inferiority, Black American Islam is thoroughly embedded in the American tradition. From the proto-Islam movements of the early 20th century to the Black separatist movements of the 1960s, heterodox communities, and orthodox communities with leaders from or trained abroad, many Muslim communities sought to address social ills in America and globally. In particular, racism, economic and social inequality, economic exploitation, and family instability are on the main agenda of many Black American Muslim leaders.

Before 9/11, some of the most prominent voices in American Islam were African Americans, including Warith Deen Muhammad and Siraaj Wahaj. Their status as citizens afforded them the privilege to critique American society and foreign policy, without compromising their Americaness.

The protest tradition of many leaders helped forge a space for the next generation of immigrants and descendants of immigrant Muslim Americans to assert themselves in the public sphere. Following the events of 9/11, there has been an increasing silencing of Black American Muslim voices: a combination of little to no media acknowledgment of BAM’s as well as a systemic neglect on the part of immigrant Muslims.

Over time, Black American spokespeople were gradually eclipsed as national Muslim organizations with strong immigrant interests sought to assert their agendas and provide the dominant narrative of immigrants assimilating to American values.

In contrast to the hegemonic narrative that has rendered them invisible, Black American Muslims are vital to the health of this diverse Muslim community. They have also continued to make great strides politically, socially, and culturally. This includes two Black Congressmen, Keith Ellison and Andre Carson, the growing prominence of intellectuals and scholars, most notably feminist scholar, Amina Wadud, and Aminah Beverly McCloud, who wrote African American Islam, Sherman Abdul-Hakeem Jackson, and Zaid Shakir.

There are also many young scholars, such as Jamilah Karim, Su’ad Abdul Khabeer, and Intisar Rabb. There is a large wave of Black American Muslim leaders who have demonstrated mastery of Islamic sciences and have graduated from Muslim institutions of higher learning, including Abdullah Ali, who earned a degree from Al-Qarawiyin University of Fes.

Black American Muslims have made cultural gains including a feature-length film, “Mooz-lum,” and prominent Hip Hop artists, including but not limited to Lupe Fiasco, and Yasiin Bey (Mos Def). The Abdullah brothers shared their story of taking time off from the NFL to perform the annual Muslim pilgrimage (Hajj). The fencer, Ibtihaj Muhammad, was the first Muslim woman to compete for the United States in an international competition and win a medal.

Black American Muslims are very much part of the fabric of America and often play a daily role in interfaith dialogue, as many of them have family and loved ones who are non-Muslim.

Black American Muslims are vital to the health of this diverse Muslim community

Black American Muslims have used their social capital to critique American foreign policy, Islamophobia, and erosion of American civil liberties. As a group, Black American Muslims are far from nativists, as many identify with and relate to numerous international and transnational Muslim communities. They are much more likely to attend a mosque in which another group dominates, showing their willingness to assimilate into an immigrant dominant mosque.

Black American Muslims participate in anti-war protests, critique extra-judicial killings through drone strikes in Chad, Mali, Yemen, and Pakistan, raise money for war refugees in Syria, and alleviate suffering in natural disasters in Somalia and Pakistan. Yet pressing social issues in their home communities, such as economic inequality, street violence, and family instability, play a large role in their everyday lives. Crime, poverty, and marriage are common issues raised in the Black American Muslim discourse from the minbar to the lecture hall. These issues also shape their outlook, which in turn causes them to be empathetic to the plight of others at home and abroad.

Perhaps the flexibility of thought can be tied to the Black American Muslim identity, which is comprised of multiple intersections. They are connected to many faiths and ethnic groups as part of this nation-building project that we call the United States of America. They are connected to many faiths and people who were either forcibly or willingly migrated to other lands as part of the African Diaspora. They find connections with people on the African continent, and Black communities in South America and the Caribbean. They are also connected to people all over the world in a multi-ethnic global community, ummah. These connections have given Black American Muslims a unique juncture to relate to and speak on various issues and causes. Black American thinkers continue to be influential in defining American Muslim thought, as they connect their day-to-day lives with Muslims globally.

It seems to be willful ignorance on the part of the media, scholars, and some organizations to overlook these important contributions and connections. The occlusion of Black Americans despite the continual relevancy of Black American Muslim thought makes it especially important to document this intellectual heritage. Indeed, we must go beyond documenting the life histories of major Muslim leaders and begin to study transformations in Muslim American thought.

I look forward to the next wave of scholars who study Black American Muslims, such as Donna Auston, Zaheer Ali, and others who will shed light on the roots of Black American Islam. These scholars can help us look at the ways in which Black American Muslims drew upon their intersecting identities in their interpretations of textual traditions in ways that address their global and local issues. I look forward to future studies of our rich intellectual traditions and the insights that these brilliant scholars can bring to the discussion about American Islam.

This article was first published on Sapelo Square by author Margari Aziza Hill. You can find the original article here.