Racism is not just about committing wrongs or injustices against another group; it is the attempt to remove some groups of people from the category of human.

Racism is not just about committing wrongs or injustices against another group; it is the attempt to remove some groups of people from the category of human.

For Black people, your entire life is a struggle to breathe — a war to not suffocate. This battle to stave off “loss of breath,” to fight the routine strangulation at the hands of oppressors, is broader than physical combat. It is a battle for life and meaning — a battle that is essentially human and essential to Islam.

And this fight comes with questions: why is my skin tarnished, frightening? Why am I unwanted? Why is my community impoverished? Why are ugly names cast my way? Why am I not allowed to be a being of my own choosing? Why must I be a being of someone else’s choosing? In a world where air is rare and freedom is torn away, war is stitched into our bodies. “I can’t breathe” is more than a description of physical assault, it is diagnostic; it is a summary of the symptoms of lived pain and agony at the hands of a racist society.

Of course, every person faces an ethical battle. We must figure out the meaning of the world. Life must make sense. Although you do not choose your beginning, you must choose your end. But anti-Black racism, which defines so precisely how Black people should both live and die, casts this battle in dramatic terms. When you lose your breath, it means that the inability to choose who you are defines not only your beginning but also your end.

For many Black people, the response is clear, “we choose nothing, we choose nihilism.” The nihilism that often emerges — not just the belief that the world has no meaning but the intense loss of love, hope, and faith — helps explain the difficulty faced in overcoming oppression. It gives an opening to understand the tragic turn away from life toward recklessness and despair.

You choose to believe in the meaninglessness of everything when they face their radically circumscribed, seemingly arbitrary circumstances and weep. To face nihilism, to feel the destructive tinge of meaninglessness is a confrontation that we must face in our journey towards meaning.

Perhaps this is why Black life is marked with the pervasive loss of breath:

This is Bigger Thomas from Richard Wright’s epic Native Son, saying, “You know where the white folks live?… Right down here in my stomach… Every time I think of ‘em I feel ‘em… And sometimes you can’t hardly breathe.”

This is Lorraine Hansberry penning in A Raisin in the Sun, “Men everywhere like to breathe; and the Negro citizen still cannot, you see, breathe.”

Or Baldwin, “I needed to be in a place where I could breathe and not feel someone’s hand on my throat.”

This is Fanon in Black Skin, White Masks, “it is true that I have to throw off an attacker who is strangling me, because I literally cannot breathe…”

Eric Gardner and George Floyd, “I can’t breathe; I can’t breathe, ”I can’t breathe.”

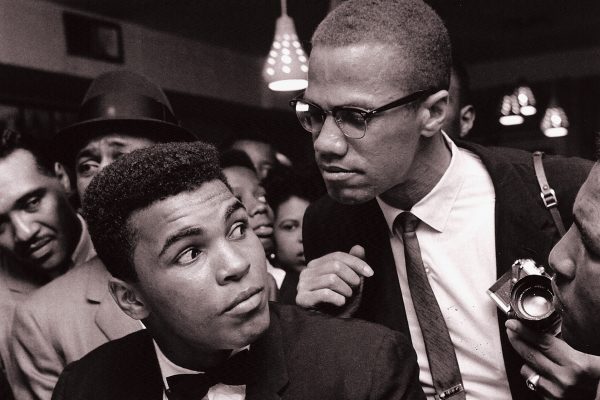

And this is Muhammad Muhaymin Jr., “I cannot breathe…Please Allah!”

This is what it means to be in an all-out war against unjustified racism. The fight for Black life, then, is a fight not only against oppression but also meaninglessness. Indeed, the everyday fight waged against oppression is a fight against meaninglessness — a fight for value, for hope, for love, and for belief. At the very least, in war and loss of breath, we have identified the ultimate spiritual struggle. It begins with a fight to give oneself the space, the air to make meaning of things. With this, it is proper for us to say that the Black struggle of existence is simply to grasp, painfully, for air…

If war is in part a struggle for air, what then are we to make of the child? Pushed out into the world for the first time, its lungs expand, the infant shrieks and wails. The cry of the baby, bare and innocent, not tarnished by the real war to come yet desperately in need of oxygen, begins. The baby is also locked in an immediate battle for life.

But the child’s struggle for air is also greater than a simple physical reaction. Prophet Muhammad ﷺ teaches, “There is none born among the off-spring of Adam, but Satan touches it. A child therefore cries loudly at the time of birth because of the touch of Satan.” Thus, Satan’s hatred for man is present at the moment of birth. This touch is interpreted in a few ways.

For Al-Qurtabi the crying of the baby points to the very first moment when Satan seeks to influence and control the child of Adam 1. For some, the cry occurs due to the distress and difficulty that the child is bound to face in the life of this world. For others, it is the exact, physical disruption and annoyance that causes the cry. For our purposes, no matter the interpretation, here is the Muslim’s battlefield.

Like the condition of the Black child of Adam, every beautiful creation of Allah, the Majestic and High, regardless of tongue or skin is in a struggle for meaning, at war from their first breath. Let us look at what Allah, the Glorified, says about humanity’s two paths.

Satan threatens you with poverty and orders you to immortality, while Allah promises you forgiveness from Him and bounty. And Allah is all-Encompassing and Knowing (Q 2:268)

That is only Satan who frightens [you] of his supporters. So fear them not, but fear Me, if you are [indeed] believers (Q 3:175)

And say, “My Lord, I seek refuge in You from the incitements of the devils” (Q 23:97) (translation: Sahih International)

It is clear that Satan calls mankind to the very nihilism that so many seem bound to. Each ayah of course has its context-specific interpretation but at its base, the evil propagated is that which causes a loss of morality, hope, and belief in Allah.

These ayahs also shed light on another side of the spiritual battle so central to human life. If we look closely, we see that evil and godlessness is attributed to Satan. While those who perpetuate evil wish to convince the oppressed that nihilism is always present in their lives, this only hides their own emptiness. So, we can understand “I can’t breathe” in yet another way. It was never just a diagnostic; it has always been a demand to breathe, a demand for life.

In the world of the believer, the fight to not choke to death is forever tied to the fight to submit to Allah. God-consciousness is in and of itself a breath. It is at first a breath in; of the stress, the trauma, the pain, the doubt, the intensity the hate. Then, it is a breath out, it is a look beyond the bonds of oppression and refusal to strip the world of its divinely crafted purpose. The demand to breathe is the desire to implement Allah’s will, to draw near to Him, for He is the one who ultimately gives and takes away our breath.

While it is clear that Satan’s arrogance and privileging of lineage suggests racism, beneath the surface we should recognize the hatred here is of humanity defined according to Allah’s will. Racism is not just about committing wrongs or injustices against another group; it is the attempt to remove some groups of people from the category of human. In the propagation of evil, the world loses its significance and life is rendered worthless. This is an attempt to transform the very idea of what it is to be human by unhinging us from attachment to Allah. This war then has always been a battle for humanity.

It does not surprise us that “I can’t breathe” is the slogan at the center of massive global uprisings. At its core, we know that the existential war of Black life is naught but a more dramatic, visible form of the spiritual battle tasked with every creation. Not only is this fight against that most obvious oppression of others but, perhaps just as deeply, the oppression of despair and hopelessness that creeps in when the air thins around us. Nihilism is but a tool of the evildoers who wish to both stomp out dissent and quell righteousness.

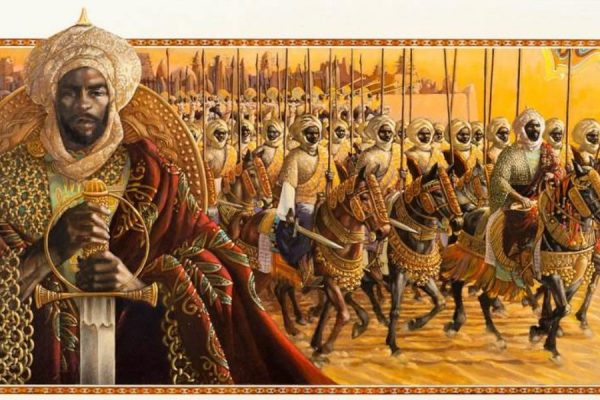

In recognizing this, we can take solace knowing that these battles are not unique to a modern movement. Put differently, perhaps it is most appropriate to say that when we do not bear witness to the social, existential, and ultimately spiritual wars that Allah has commanded us to wage — those wars represented so intensely in Black life — that is also a loss of breath.

This article was first published on Sapelo Square, written by author Iesa Abdul-Haqq. You can find the original article here.