Labelling Afghanistan “the graveyard of empires” is, at best, historically illiterate and, at worst, utterly self-serving. It not only negates thousands of years of Afghanistan’s history as a flourishing centre of civilisation, but also — in an act of supreme imperial hubris — shifts the blame for U.S. failures there onto the land and people of Afghanistan themselves.

Labelling Afghanistan “the graveyard of empires” is, at best, historically illiterate and, at worst, utterly self-serving. It not only negates thousands of years of Afghanistan’s history as a flourishing centre of civilisation, but also — in an act of supreme imperial hubris — shifts the blame for U.S. failures there onto the land and people of Afghanistan themselves.

This article was originally written for Ajam Media Collective by author Alexander Hainy-Khaleeli. You can find the original article here.

In recent days, the world has watched in shock as the Taliban returned to power in Kabul, rapidly overpowering Afghanistan’s government and heralding the failure of the United States’ decades-long mission there.

In a speech delivered on August 16, President Biden defended his decision to withdraw U.S. troops from the country — the action that precipitated these events — by invoking a popular cliché:

“The events we’re seeing now are sadly proof that no amount of military force would ever deliver a stable, united, secure Afghanistan, that is known in history as the graveyard of empires.”

Biden labelling Afghanistan “the graveyard of empires” is, at best, historically illiterate and, at worst, utterly self-serving. It not only negates thousands of years of Afghanistan’s history as a flourishing centre of civilisation, but also — in an act of supreme imperial hubris — shifts the blame for U.S. failures there onto the land and people of Afghanistan themselves.

But where did this phrase come from? What does it mean? And why is it flat out wrong – and even racist?

It may sound like timeless wisdom, but Afghanistan’s epithet “the graveyard of empires” appears to have been coined only recently — so recently, in fact, that it doesn’t even predate the U.S. invasion. It first appeared in 2001, in a Foreign Affairs article by the CIA’s former Pakistan Station Chief Milton Bearden, titled ‘Afghanistan, Graveyard of Empires.’

In the article, Bearden cautioned against a U.S. occupation of Afghanistan based not only on the historical experiences of the Soviet Union and the British Empire, but also of Alexander the Great, Genghis Khan, and all “the world’s great armies on campaigns of conquest” who “eventually ran into trouble in their encounters with the unruly Afghan tribals.”

This argument reduced the history of Afghanistan to a history of its invaders and dismissed the Afghan people as backwards and savage, recycling classic orientalist tropes for a “War on Terror” audience.

Most importantly, however, Bearden’s argument is utterly at odds with the realities of history. Alexander the Great and Genghis Khan not only conquered Afghanistan, their successors ruled it for centuries after them and adapted themselves to its culture and religion. Far from being a place where empires go to die, the land of Afghanistan was, for millennia, a place in which they thrived and prospered, thanks in part to its strategic location at the crossroads of Asia. It is only to be expected, then, that many great empires also emerged from Afghanistan to make their mark on world history.

Consider the Kushans (30–350 AD), who ruled over stretches of Afghanistan, Central Asia, and Northern India from their capital at Bagram (yes, like the airbase) and traded with Rome, India, and China. Under the Kushans, Afghanistan was home to a flourishing civilisation that combined Greek and Indian influences with Buddhist heritage to give rise to a unique and eclectic artistic tradition. In fact, some of the earliest representations of the Buddha in human form are believed to originate from this period.

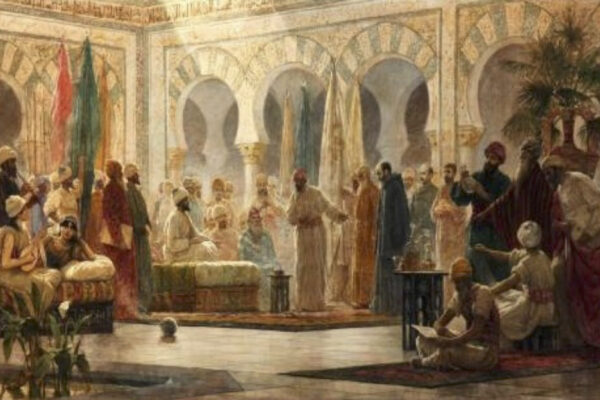

The Kushans were just one of the many historic civilisations to have prospered in what is now Afghanistan. The Ghaznavids (977–1186), based in Ghazni, were a Turkic Muslim dynasty who were enthusiastic patrons of art and architecture. Under their patronage, Persian emerged as a language of poetry and high literature in the Islamic East; the great poet Ferdowsi dedicated his Shahnameh, or Book of Kings, the national epic of the Persian world, to Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni.

The Timurids (1370–1526 AD) were also renowned for their sponsorship of grand buildings and great works, and their reign left an indelible mark on Persianate culture. The Timurid capital at Herat positively buzzed with artists, craftsmen, and men of letters. Babur, the founder of the Mughal Empire, famously quipped that you could not stretch your legs in Herat without kicking a poet!

European colonial rule in Afghanistan began in the 19th century, when the British sought to maintain it as a buffer state against the threat of Russian expansion into India. While historians generally agree that the British Empire’s experience in Afghanistan was a failure, the picture is more complicated than it first appears.

The first Anglo-Afghan War (1839–42) ended in disaster for the British, but they enjoyed markedly more success in the second one (1878–80). They did not remain to occupy the country, but they did install their chosen candidate as amir, annex territory, and reduce Afghanistan to a client state whose existence was beholden to British interests until it gained independence in 1919.

The “graveyard of empires” narrative also fails to explain why Afghanistan enjoyed a long period of relative peace throughout the monarchic era. Despite competition between the great powers for nearly five decades (1929–78), Afghanistan’s kings — beginning with Amanullah Khan in the 1920s — successfully maintained its independence and embarked on measures to develop a modern Afghan nation-state. During the Second World War, while its neighbour Iran was occupied by British and Soviet troops, Afghanistan was able to maintain its neutrality and its independence.

In the post-war period, when Middle Eastern nations such as Egypt, Syria, and Iraq were rocked by coups and counter-coups, and India and Pakistan fought a series of wars, Afghanistan appeared relatively stable. Even the 1973 coup that ended the monarchy and established the Republic of Afghanistan was virtually bloodless. It was not until the Marxist Saur Revolution of 1978 and the subsequent Soviet invasion of Afghanistan that the country began its descent into four decades of war and destruction. Hence — without wanting to idealise the past—even recent history demonstrates that the image of Afghanistan as a place of perpetual conflict and unrest is false.

It is the defeat of the Soviet Union, which invaded Afghanistan between 1979–89, that has arguably done most to cement the image of the country as singularly unconquerable. In the popular imagination, rag tag Afghan mujahideen appeared to — in the words of Ronald Reagan — “take on modern arsenals with simple hand weapons.”

However, this struggle — which was famously celebrated by the 1988 film Rambo III — was not as one-sided as it might seem. From the outset of the invasion, the mujahideen received billions of dollars of covert support from the United States, Pakistan, and Saudi Arabia. So, while it is true that the Soviets were the only superpower with combat troops in Afghanistan, they were not the only superpower fighting there.

Therefore, the course of the war was neither inevitable nor due to its “unruly” people, but rather the deliberate result of Cold War manoeuvring. Far from being a unique case, the Afghan-Soviet conflict fits into the broader pattern of proxy wars fought from Southeast Asia to Central America, and it was no bloodier or more protracted than other conflicts where the United States and Soviet Union employed local actors to wage war on their behalf. And, like elsewhere, the greatest victims of this manoeuvring were the Afghan people themselves, with over one million killed and millions more forced to flee.

Despite this complicated history, the last two decades have seen the phrase “the graveyard of empires” not only enter popular discourse on Afghanistan but also rapidly attain the status of timeless wisdom. In his The Looming Tower: Al-Qaeda and the Road to 9/11 (2006), journalist Lawrence Wright claims that by ordering the bombing of two U.S. embassies in Dar es Salaam and Nairobi in 1998, it was Osama Bin Laden’s intention “to lure the United States into Afghanistan, which was already being called the graveyard of empires” (I have yet to find any published instance of this in the English language prior to Bearden’s 2001 piece).

Meanwhile, in 2010, two books were published about Afghanistan that featured this description in their titles: Seth G. Jones’s In the Graveyard of Empires: America’s War in Afghanistan and David Isby’s Afghanistan: Graveyard of Empires. A New History of the Borderland. And even when this epithet was not directly mentioned, in books, and interviews, and think-pieces, the idea was ever-present: State-building efforts in Afghanistan were probably futile — not because of any possible flaws with the U.S. military occupation itself, but because the land and its people were inherently ungovernable.

It is not surprising, then, that President Biden explicitly invoked this trope to justify the withdrawal of U.S. forces from Afghanistan. In this speech, he characterised the U.S. mission there as “a decades-long effort to overcome centuries of history and permanently change and remake Afghanistan” before assigning responsibility for the failure of this mission to the Afghan people, to whom “we gave… every chance to determine their own future. What we could not provide them was the will to fight for that future.”

This comment is all the more shocking given that some 66,000 Afghan soldiers gave their lives fighting the Taliban over the last twenty years — a sacrifice that has largely disappeared from the discussion. According to Biden’s logic, the U.S. mission in Afghanistan did not fail because of widespread human rights abuses by its military or its support for corrupt warlords, but because the Afghans themselves proved unworthy of such an opportunity.

If the “graveyard of empires’ narrative is tempting to embrace, it is because it manages to be self-aggrandising and exculpatory at the same time. It is the ultimate humblebrag. The fact that we failed in Afghanistan somehow brings us into the company of history’s greatest empires while simultaneously absolving us of any culpability for its present state — ”Alas, we could do no better than Alexander the Great!”

It also absolves us of any duty to the ordinary Afghans who risked their lives and those of their loved ones for our promise of a better tomorrow; the interpreters, journalists, government employees, and others, who now face the very real threat of Taliban reprisals. Many of them were left stranded on the tarmac at Kabul International Airport (or worse, clinging to planes as they took off) while Westerners were being airlifted to safety.

It is certainly an opportune time for us to step back and re-assess the War on Terror and to ask how and why it failed to achieve its aims. We can (and should) look back with the benefit of hindsight and identify the reasons why invading and occupying Afghanistan was a bad idea in 2001. But we can also discuss the difficulties of governing Afghanistan without reducing the land and its people to an orientalist caricature — one that is as historically inaccurate as it is racist.

Attributing imperial failures in Afghanistan, whether historical or current, to a combination of what Nivi Manchanda (in her Imagining Afghanistan) calls a “trans-historical, congenital Afghan predisposition” and “geographic determinism,” obscures more than it reveals: It prevents any serious analysis of why America and its allies’ 20-year mission failed so badly. It precludes drawing any lessons from their experiences there. And it forestalls any moral reckoning for either the damage inflicted by the occupation or the harms that will inevitably result from our withdrawal. After all, it was broken when we got here.

Clichés such as “Afghanistan, the graveyard of empires” gain currency because they appear to explain complex events with simple truths distilled from centuries of experience. The temptation to reach for such easy answers must be resisted if we are to have any hope of understanding how we arrived at our present historical moment or of holding those responsible to account.

There are assuredly reasons for the U.S. failure in Afghanistan, and these will no doubt be hotly debated for years to come. However, as history has shown, Afghanistan being “the graveyard of empires” is clearly not one of them.