The Crisis of Masculinity narrative we have been hearing so much about over the past couple of years is nothing new; it is in fact, dangerous rhetoric imbedded in insecurity.

The Crisis of Masculinity narrative we have been hearing so much about over the past couple of years is nothing new; it is in fact, dangerous rhetoric imbedded in insecurity.

Find a man at random (let’s call him Ali) and ask: Who’s tougher – you or your father?

If Ali was fortunate enough to be raised by a father figure, his answer would usually imply that his old man is a (slightly) harder cookie than he is. Ali’s father would undoubtedly agree, noting how his son’s generation is a softer variety of biscuit – “back in my day we chewed pinecones to harden the gum-line”. I wonder, however, if you would agree that were this same question put to Ali’s father, he would also note that his father was tougher than he is.

The point I wish to highlight here is that throughout history, many men are faced with a presence and an absence that navigate their sense of masculinity. The absence is what was. Nostalgic stories of how men would act and behave in past generations. These actions and behavioural patterns are not only strongly contingent on specific historical moments, but they paradoxically act as criteria’s only achieved ‘fully’ by the past, only to be attempted today. As the famous Iranian saying goes “If you see a ‘real man’, frame him” accentuating the unlikelihood of its attainment.

What is present is a testimony to the future. It is the generation who is always corruptible, soft, weak, lazy, and unable to hold onto notions of masculinity that were historically passed on. What is absent rejects what is present, in the name of a past no longer one of integral satisfaction but one of bitter adjustment to a punitive present. This is not a malevolent conspiracy, nor is it entirely intentional, but a simple case of historical contingencies turning into natural necessities.

At a given time period, it was absolutely true that one could not simply go out into a shop and purchase the products required to make a meal. A certain discipline with respect to diet was necessary to ensure survival; anything else was a luxury. However, if those very same behaviours are applied to modern living where resources are in abundance, the restrictions of the past no longer hold onto their function; they become repressive for the sake of repression.

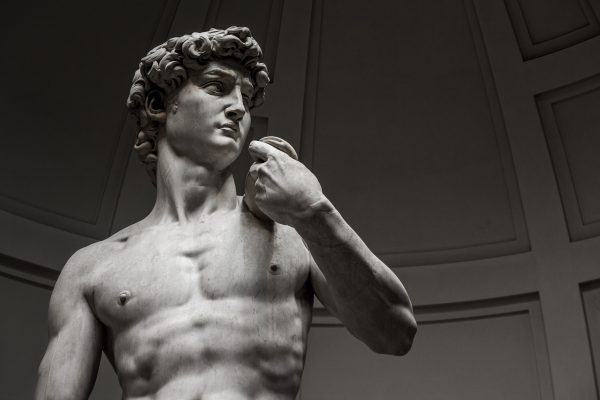

Keeping this in mind, it is also vital to note that many of the standards put on Muslim men today are neither Islamic nor do they originate from traditional outlooks. From my own experience, there is something quite unique about going a mosque during Muharram and witnessing 6-foot giants with Schwarzenegger physiques weeping to the tales of Hussain (A.S.) and his family. For many children, it is the first time they witness their fathers and brothers weep. The benefits of witnessing collective mourning of such a sort are arguably foreign to Western interpretations of manhood and their intertwining of the gender role with dry eyes.

Orientalist writings of Muslims will often caricature Muslim men as overly emotional, unable to control themselves, and to be, in a word, uncivilised. Islamophobic narratives run closely to such misrepresentations while holding onto the image of stoic Western masculinity capable of greater social and economic power. I assert that Muslim men will risk internalising such narratives if we take on board the same false notions of masculinity.

“Tears only dry up as a result of hardness of the heart, and the hearts only harden as a result of frequent sinning.” ― Ali Ibn Abi Talib A.S

The Crisis of Masculinity narrative we have been hearing so much about over the past couple of years is nothing new; it is in fact, dangerous rhetoric imbedded in insecurity. The myth that is always perpetuated is that the disciplining of reason over the Western body leaves a tempered and rational man who is in control. In the United States, the nineteenth-century ‘man of character’ was marked out by his temperance and reserve, along with his ardent sense of civic duty and devotion to hard-working industriousness.

As the twentieth century progressed, however, notions of masculinity in the West defined by work and abstinence were undermined by an aggregation of social and economic changes. The reconfiguration of labour markets, and the rise of mass consumption, together unhinged many of the traditional certainties that had been at the heart of the dominant conceptions of manhood.

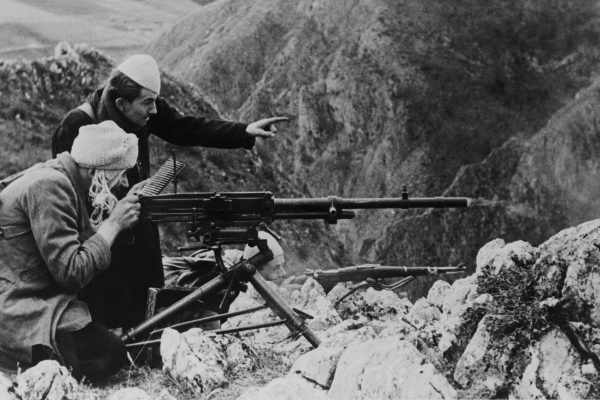

Of course, the disgruntlement of an older generation that felt their nation was being feminised, mollycoddled, and headed towards decadence was a loud one. A virile reassertion of ‘manly’ qualities was reflected in Roosevelt’s insistence for a return to ‘the doctrine of the strenuous life’, extolling the American people to ‘boldly face the life of strife…for it is only through strife, through hard and dangerous endeavour, that we shall ultimately win the goal of true national greatness’.

G. Stanley Hall (who saw non-whites as primitives and savages, while enforcing selective breeding and forced sterilisation), famously claimed that boys should be encouraged to immerse themselves in ‘primitive’ physicality so they might ‘evolve’ into more powerful and ‘civilised men.’

Is it a coincidence that we find such fascistic outlooks embedded in today’s Islamophobia, particularly messages emanating from the far-right? Brenton Tarrant, the man behind the Christchurch terror attack that killed 51 people during Jummah prayer in New-Zealand wrote: “The people who are to blame most are ourselves, European men. Strong men do not get ethnically replaced, strong men do not allow their culture to degrade, strong men do not allow their people to die. Weak men have created this situation and strong men are needed to fix it.” Once Muslims begin to adopt such logic, there is a risk of playing into the Clash of Civilisations argument which is based on a flawed ahistorical understanding of culture which cannot be sustained but may well do a great deal of damage.

“Our followers are like bees which live among birds. None of the birds recognise the bees because of their small size and weakness. They would not treat them this way if they realised that these very small bees can carry honey which is very valuable in their stomachs.” ― Ali Ibn Abi Talib A.S