Of course, many Muslim women have wielded vast political power, ruling entire empires (Sofieva herself was probably named after the great Safavid princess, poet and politician Peri-Khan Khanum), and some were likely elected in less formalized ways. But Sofieva’s case represents the first time a Muslim woman ran in a modern election – complete with ballot boxes, party lists and formal campaigns – and won.

Of course, many Muslim women have wielded vast political power, ruling entire empires (Sofieva herself was probably named after the great Safavid princess, poet and politician Peri-Khan Khanum), and some were likely elected in less formalized ways. But Sofieva’s case represents the first time a Muslim woman ran in a modern election – complete with ballot boxes, party lists and formal campaigns – and won.

This story was originally published on Eurasianet, by author William Dunbar.

The village of Karajala is fairly typical of the dozens of settlements populated by Muslim Azerbaijanis that stretch southeast between Tbilisi and Georgia’s border with Azerbaijan. It’s a place of relative prosperity, where men drink tea in chaikhanas and women in colorful headscarves patrol large domestic compounds.

But one hundred years ago, it was the site of a remarkable world first. Records recently unearthed by historian Irakli Khvadagiani show that in 1918, Karajala became the first place in the world to democratically elect a Muslim woman into office.

Her name was Peri-Khan Sofieva, but very little is known about Sofieva herself, not even her date of birth. All that survives is her signature in the official records, a possible photograph, her grave, and the folk memories of the elders of Karajala. They remember “Peri-Khan the man,” an indomitable figure armed with a Mauser pistol and smoking a pipe, almost unimaginable in the firmly patriarchal Azeri society of today. But Sofieva’s story resonates far beyond the confines of sleepy Karajala, reflecting the huge promise and terrible losses Georgia experienced in the first half of the 20th century.

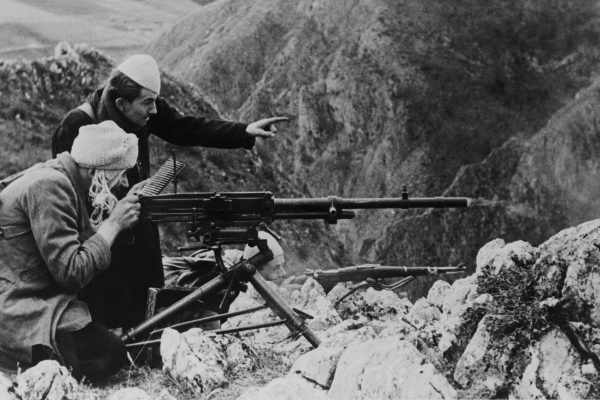

In 1918, Georgia was just embarking upon a daring experiment in modern democracy – one that would be crushed by the Bolsheviks after only three years. Amid the chaos of the First World War and the Russian Revolution, the Democratic Republic of Georgia declared its independence and set up a social democratic, multi-ethnic state, with a constitution enshrining universal suffrage, minority rights and freedom of religion. One of its first acts was to hold local elections, to provide democratic accountability at the village level.

“The top politicians thought that a real democratic state is built from a base of villages. That ‘Village Society’ is the key point in the whole political system. If there is a problem in the village and if democracy is low, if political culture is low, then there is no basis to build a real and good democratic society on,” explains Khvadagiani, whose organization Sov Lab is devoted to researching the Soviet past in Georgia.

It was while researching a book on local government in the Democratic Republic of Georgia that Khvadagiani came across the name Peri-Khan Sofieva – clearly the name of an Azerbaijani woman – in a journal detailing regional representatives in Tiflis district, which at the time contained Karajala. “The first time I saw her name in that journal, my reaction was ‘wow,’” says Khvadagiani, who followed the archival paper trail to the electoral lists for Karajala, and her signature, written in Russian script, on the protocol listing her as a regional representative.

The archive documents show that Sofieva ran as an independent in the elections in 1918, competing against candidates from Georgia’s nationwide political parties, parties that swept the board in most parts of the country. “Her victory shows how much influence and authority she must have had in her village,” Khvadagiani explains. “This appears to be unique.”

“When you look at the picture you see what an important person she must have been for the whole community, that they gave their votes to her – a woman.”

Universal suffrage in 1918 was not unique to Georgia. Women voted in and were elected to the abortive constitutional assembly in post-imperial Russia, while New Zealand granted women the vote back in 1893. But Georgia was one of very few places with a sizeable Muslim community where women could vote. Neighboring Azerbaijan, which also declared its independence in 1918, was the first majority Muslim-majority country in the world to declare universal suffrage, but no women were elected to its parliament after elections in December 1918. Georgia also elected five women and three Muslim men to its own parliament in 1919, a year after the local elections.

It is therefore almost certain that Sofieva was the first Mulsim woman to be elected formally anywhere in the world. Of course, many Muslim women have wielded vast political power, ruling entire empires (Sofieva herself was probably named after the great Safavid princess, poet and politician Peri-Khan Khanum), and some were likely elected in less formalized ways. But Sofieva’s case represents the first time a Muslim woman ran in a modern election – complete with ballot boxes, party lists and formal campaigns – and won.

The significance of her election was not lost on the Georgian media in 1918. Sakhalkho Sakme, the main newspaper of Georgia’s opposition Socialist Federalist party, the party defeated by Sofieva in Karajala, celebrated her victory: “We should mark one joyful moment: In the list of elected representatives there is a Muslim woman – Peri-Khan Sofieva.”

“The press was saying that it’s such a great event that we have a Muslim woman elected. It was a measure of the level of democracy and the culture of the elections,” says Khvadagiani. But it was a great event that was forgotten almost immediately, even in Sofieva’s native village, as the democratic potential of 1918 faded against the memory of the horrors that followed.

Karajala (Karajalari on Georgian maps) today is full of Sofievs. In the corridors of its enormous school, a Soviet building recently refurbished, the surname is plastered on all the notice boards. Khvadagiani has come here to try to track down some of Peri-Khan’s descendants, to attempt to fill the huge gaps in what we know about her, and to find out if people here are aware of her place in history. As we are led into the principal’s office, it’s clear the search will not take long.

Beg Zadr Sofiev is the school’s history teacher, and Peri-Khan’s great nephew. Smartly dressed and in his fifties, he is too young to have known Peri-Khan personally, but for people of his generation, the legend is strong.

“All the elders in this region know her and know about what good things she did,” Beg Zadr says. “She was very active, helping everyone. And at that time you can imagine what condition people were living in here: she was always trying to help them somehow,” he explains, conjuring a female Robin Hood.

The small crowd of teachers who have gathered in the principal’s office nod in agreement.

“She was very brave and manly, and very strange, a very unusual woman. She smoked a big pipe and all the time she was very dominant. Every time she had negotiations and discussions with men she was the dominant one,” Beg Zadr continues. This is almost completely unimaginable in the Azeri community in 2017, where many women leave school to get married before they turn 16, and gender discrimination is commonplace. There are no elected female Azerbaijanis in Georgia today – indeed, even smoking is often seen as socially unacceptable for Azeri women.

Beyond the pipe-smoking philanthropist of Karajala’s folk memory, another side of Sofieva emerges. She was one of nine children – the only girl – and from back in the Tsarist era (when, relatives say, she persuaded the Imperial Russian government to run a new railway line close to the village) she acted as the head of her band of siblings, negotiating loans from banks and dealing with the authorities. It becomes possible to see how an intelligent woman with a head for business and eight brothers supporting her might become de facto head of a village like Karajala.

Across the village is the house of Rakhshanda Sofieva, the widow of Peri-Khan’s nephew, and one of the few people still alive in Karajala who remembers Peri-Khan personally. Tiny, exuberant and well into her 80s, it’s tempting to speculate that more than a little of Peri-Khan rubbed off on her. She is the only person we meet who is aware that Peri-Khan was elected to represent the village in 1918, and she is delighted to reminisce.

“Oh Peri-Khan, rest in peace,” she sighs. “She was such a woman! She was a man, but born as a woman. Men were afraid of her. Her word was very powerful. Nobody would risk going against her. If there was ever a question about the life of the village, people would ask Peri-Khan. […] Her word was like law. If she said come, you had to come, if she said don’t go, it meant you could not go.”

According to Rakhshanda, Peri-Khan, at the head of her band of siblings, remained the dominant force in village life even after the Bolsheviks came to power, acting “like a minister.” She read from the Quran at weddings and funerals “like a mullah,” dispensed advice and charity – and always carried a German revolver at her side. “Nobody could suppress her, not the Soviet government, not anyone else.”

Her brothers were not so lucky.

During Stalin’s Great Terror of 1937, five of Peri-Khan’s eight brothers were executed. “They were rich and were shot for it,” says Rakhshanda, who was a child at the time. She describes how the brothers were taken “to the marsh” and killed. The ‘marsh’ is most likely a large mass grave of victims of the Terror, its location still unidentified.

Executions like this characterized the Terror, says historian Khvadagiani, who also leads a project dedicated to locating Soviet mass graves in Georgia. “It’s hard to know exactly why they were shot. In the archive there will just be a one-page protocol authorizing the execution. It will say he was an enemy of the people. Maybe because of their social status. Maybe because they were against collectivization, or against Soviet authoritarian rule. That was enough to kill without any kind of explanation.”

The purges essentially put an end to Peri-Khan’s public life in Karajala, and she dedicated the rest of her days to protecting what remained of her family. Children and relatives of ‘enemies of the people’ faced massive discrimination. Often deported into internal exile, even the ones allowed to remain were effectively disqualified from higher education, government jobs and housing. After her brothers were killed, Peri-Khan raised their children as her own, and did her best to shield them from the state. “She was like a mother to them, she survived for them, she raised them and gave them the possibility to get a higher education. They became doctors, teachers, high professionals,” Rakhshanda says. “Peri-Khan. Ah, she was such a woman.”

Peri-Khan’s great-nephew Beg Zadr says a prayer as he stands beside her grave, hands outstretched and palms turned upwards in the Azeri fashion. This part of Karajala’s cemetery is reserved for Sofievs. Some graves are adorned with life-sized photographs of the deceased etched into black marble, others marked by roughly hewn stones sticking into the ground at alarming angles. Peri-Khan’s is a modest outline of stones arranged in a rectangle. Nearby, we find a large brick mausoleum housing one of the nephews she raised, a magnificently mustachioed man who died in 1978 – he must have become rich to afford such a monument. In front of it there are more memorials, cenotaphs for Peri-Khan’s executed brothers, their bodies remain somewhere in the unidentified mass grave, “in the marsh,” in the words of Rakhshanda.

Peri-Khan herself died in 1953, the same year as Stalin. According to her descendants, she died of shock after hearing of the arrest of one of her nephews. Although she was almost certainly the world’s first elected Muslim woman, she died in a country that had neither free elections nor freedom of religion, and she is remembered as “Peri-Khan the man,” not “Peri-Khan the democratically elected.” Even her great-nephews say it would be impossible for an Azeri woman to be elected in such a way today. They dismiss the idea as slightly crazy, not part of the culture.

But Rakhshanda, who knew Peri-Khan personally, thinks differently. “Without education, it’s impossible. But if a woman is educated like Peri-Khan was – then, she can do everything.”